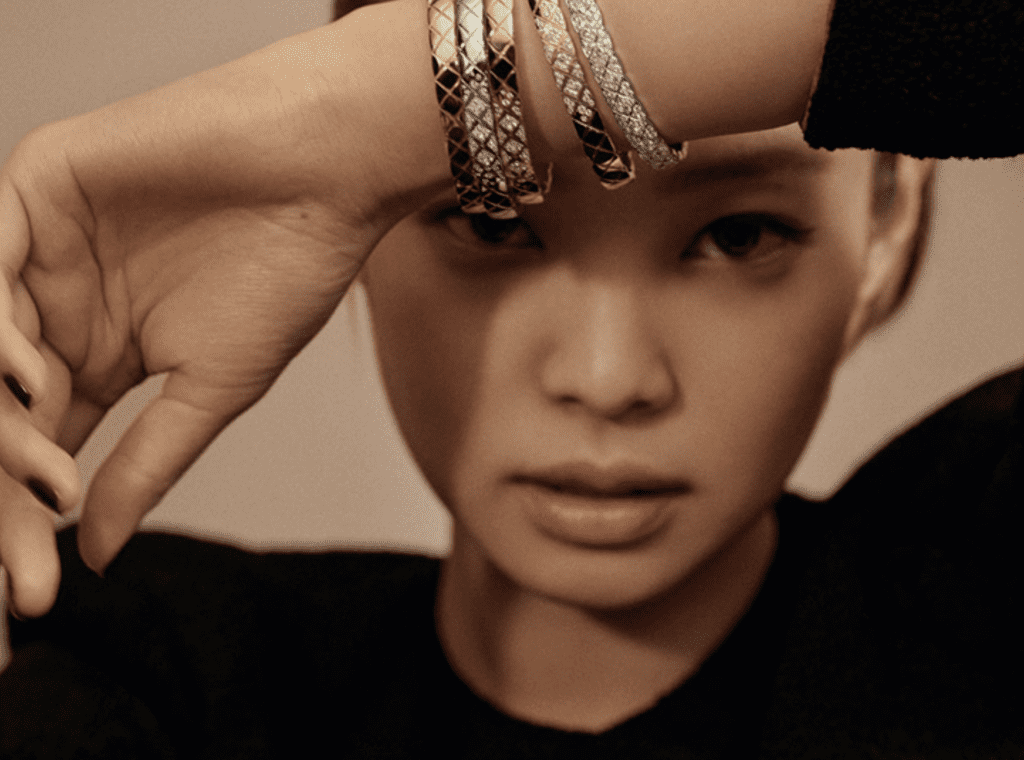

Chanel has reached a settlement in the trademark infringement and dilution lawsuit that it waged against a company in the business of upcycling and selling jewelry constructed from allegedly authentic Chanel buttons. In a filing on November 14, Chanel and defendant Shiver + Duke (“S+D”) alerted a New York federal judge that they have “reached a settlement in principle,” and requested that the case be “discontinued without costs to any party and without prejudice to restoring the action to this Court’s calendar if the parties are unable to memorialize their settlement in writing by December 14.”

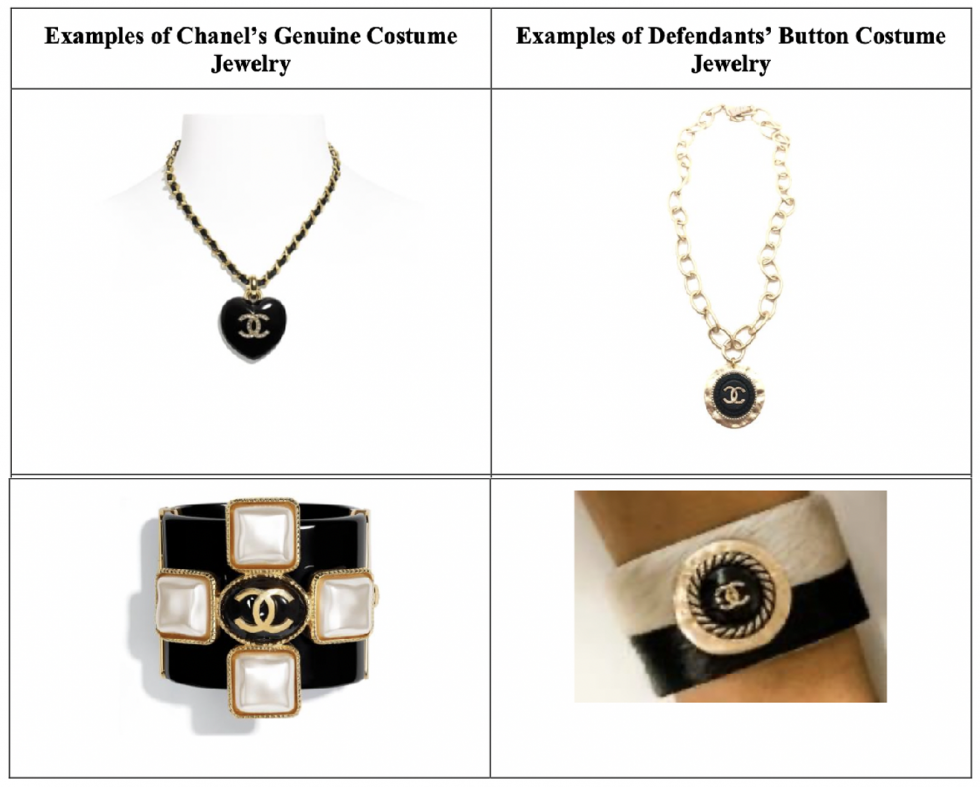

The settlement comes after Chanel first filed suit against S+D in February 2021, alleging that by upcycling and selling jewelry featuring Chanel’s interlocking “C” logo, Atlanta-based S+D – and its founder Edith Hunt – were engaging in federal and state law trademark infringement, unfair competition, and trademark dilution. On the heels of Chanel filing suit in February 2021, S+D argued that the case should be tossed out on the basis that Chanel lacks the necessary personal jurisdiction over it in New York state. Among other assertions, S+D further argued in its motion to dismiss in May 2021 that Chanel lacked jurisdiction, as under New York law, “a court may exercise personal jurisdiction over a nonresident …within the state only if the nonresident expects or should reasonably expect [its] act to have consequences in the state.”

Here, S+D alleged that it “had no reason to expect” that its actions could subject it to a lawsuit because “all of its actions were taken in accordance with, and under the protection of, the First Sale Doctrine, which generally permits the resale of trademark-bearing items after they have been sold by the trademark holder, assuming the items are not materially different and that they still meet the trademark holder standards of quality.

The court ultimately sided with Chanel, holding in September that S+D had not only transacted enough business in New York state to face litigation there but had failed to sufficiently show that the case should be transferred.

While it is not clear what the terms of the parties’ settlement include, it is almost certainly not a coincidence that all Chanel logo-bearing jewelry has been removed from S+D’s website. (Other jewelry that was made from Louis Vuitton and Gucci hardware, buttons, and canvas that was previously available for sale on the S+D website has similarly been removed.)

The State of Upcycling Cases

The outcome in the Chanel lawsuit marks the second upcycling settlement in as many months, with Louis Vuitton reaching a deal (complete with a $600k-plus judgment offer) in the lawsuit that it filed against an “upcycler” early last year. These cases, and others like them, indicate brands’ enduring willingness to take action against what they characterize as attempts by third parties to piggyback on their trademarks and the goodwill associated with those marks under the guise of upcycling. These cases also appear to drive home the point that upcycled goods might not fall neatly within the protections of the first sale doctrine, despite what the defendants routinely argue, as they are almost always materially different from the original goods offered up by the trademark-holding brands. And still yet, this growing string of cases may also suggest that brands want the exclusive right to upcycle; Louis Vuitton, after all, introduced upcycled sneakers a couple of years ago under the direction of late menswear director Virgil Abloh.

One of the interesting elements at play in many of these cases is the weight that the defendants routinely place on their use of disclaimers that detail the nature of the allegedly infringing products, and that should, they argue, shield them from infringement liability. In the Chanel case, S+D argued that it uses an array of “disclaimers” to alert consumers that it and its products are “not affiliated with Chanel,” thereby, lessening the likelihood of confusion. S+D alleged that it includes “disclaimers to its website, [its] product packaging includes disclaimers, and [there are] disclaimers permanently affixed to the products” in order to “ensure that point-of-sale confusion would be impossible.”

(Even with such disclaimers at play, S+D claimed that in a pre-suit correspondence, counsel for Chanel argued that they would not “cause a consumer in the post-sale context to believe anything other than that these pieces are from or authorized by Chanel.”)

Sandra Ling Designs, one of the defendants in the Louis Vuitton case, similarly asserted that it included disclosures with each of its upcycled goods, in which it disclaimed any affiliation with or connection to Louis Vuitton and stated that “the purchaser of the upcycled product ‘understands and acknowledges that the product is not a Louis Vuitton product” – even if the goods bore prominently-placed Louis Vuitton trademarks.

“Case law on upcycled products is fairly sparse,” Cooley LLP’s Bobby Ghajar and Dina Roumiantseva state. But based on some of the decisions that we do have, including the Supreme Court’s 1924 holding in Champion Spark Plugs v. Sanders, they note that “full and accurate disclosures are highly relevant to the [infringement] analysis and can help mitigate the risks under the Champion standard, and provide evidence of good faith intent.” Beyond that, “Evidence that the final product is of high quality and will not be the target of consumer complaints may also be relevant.”

Perkins Coie’s Grace Han Stanton and Colleen Ganin echoed this sentiment, stating that upcycling is “a fairly novel area for courts,” and the outcome in at least one case“illustrates that these cases often are not clear-cut.” In its a 2020 decision in Hamilton International Ltd. v. Vortic LLC, a U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York judge held that Vortic’s use of Hamilton marks in connection with its sale of refurbished watches was not likely to cause consumer confusion due to its “full disclosure” that the watches were created with Hamilton watch parts but otherwise not affiliated with Hamilton. The court found that the Vortic’s use of the Hamilton mark on the watches “was permissible even if [Vortic] gets some advantage” in the process, Stanton and Ganin noted.

The Second Circuit upheld the lower court’s determination in September 2021, serving to muddy the waters to an extent, as Ghajar and Roumiantseva assert that decision was “somewhat of an outlier in a series of prior cases on watch modifications.”

Looking at the industry-wide onslaught of upcycling and customization efforts, and the potential mixed messages from courts, Stanton and Ganin say that one way that brands may be able to hedge against third-party misuse is by “producing their own upcycled merchandise.” By actively participating in the circular economy, “fashion and apparel brands can contribute to sustainability while properly controlling their trademarks downstream.”

UPDATED (Nov. 30, 2022): The final order and judgment is here.

The case is Chanel, Inc. v. Shiver and Duke, LLC, et al., 1:21-cv-01277 (SDNY).