In an interesting turn of events, Chanel and Saint Laurent recently ran a co-branded advertisement in WWD, stating that French fashion and couture houses need to “protect true creativity and ingenuity from parasitical companies whose business models depend on plagiarism and counterfeiting.” In addition to noting the critical role that high fashion and couture houses play in terms of the “heritage of France” and highlighting “their ability to inspire millions of people around the world contribute to the global influence of French industry,” Chanel and Kering-owned Saint Laurent stated that they “have a long history of mutual respect and are aligned and support each other in defending creation against all attempts from actors whose business models undermine or dilute the value of their creations and investments.”

The joint ad is certainly noteworthy given the apparent alliance between the two distinct fashion entities. But more than that, it is intriguing because it comes on the heels of a striking interview that Chanel president of fashion Bruno Pavlovsky gave in May, in which he did not mince words about Saint Laurent creative director Anthony Vaccarello’s Fall/Winter 2021 collection. “How sad to see a brand like [Saint Laurent] parasite another brand,” Pavlovsky stated, presumably in reference to the array of tweed jackets that appeared in the collection.

“Saint Laurent is a magnificent brand,” Pavlovsky continued in an interview with WWD, noting, “I think it’s such a shame not to write your own history and to have to sponge off someone else. But the customers won’t be fooled. The customers will decide which brand makes the most beautiful tweed jacket. I’m not too worried.” The Saint Laurent tweed jackets have since hit shelves, selling for upwards of $3,000.

Pavlovsky did not name-check any of the other brands that have shown tweed jackets in recent seasons; in an article in October, Vogue noted to the onslaught of similar looks from the likes of Valentino, Balmain, Marc Jacobs, and of course, Saint Laurent, among others, giving readers a peek at offerings that are “not your mother’s tweed.” Quite notably, Chanel’s head did not mention LVMH-owned Celine’s showings, which prompted a comparison to Chanel’s famed use of tweed from Vogue in its review of Hedi Slimane’s F/W 21 collection. (More about the use of “Chanel-ish” in a moment.)

In response to questioning from WWD about what prompted the advertising tie-up, a rep for Chanel told said that it was “not directed at any company in particular,” and instead, is a message meant to convey that “our common commitment to protect creativity and savoir faire from business models that depend on plagiarism and counterfeiting.” Both Chanel and Saint Laurent “are aligned and, where appropriate, will support each other in defending creativity from parasitical business practices,” Chanel’s spokesman stated, declining to comment on whether the ad was the result of “any legal action.” (It is unclear what, exactly, that the grounds for legal action would be; although it is not impossible to imagine that Pavlovsky’s strongly-worded interview led to a conversation between the two companies’ counsels.)

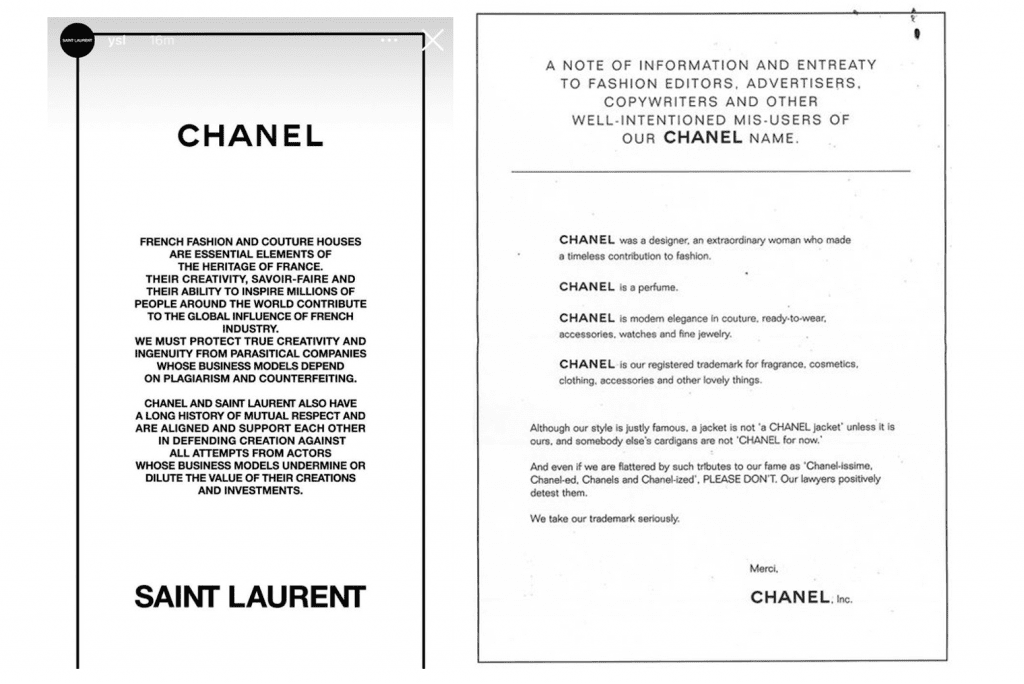

In his interview back in May, Pavlovsky stated that “more than ever, the Chanel silhouette anchors the brand,” and it is an aspect of the brand “that is extremely important for us.” This language echoes messaging that Chanel has been sending for more than a decade by way of print ads directed at “fashion editors, advertisers, copywriters, and other well-intentioned mis-users of [the] Chanel name.”

“Although our style is justly famous,” Chanel states in the recurring ad that “a jacket is not ‘a Chanel jacket’ unless it is ours, and somebody else’s cardigans are not ‘Chanel for now.’ And even if we are flattered by such tributes to our fame as ‘Chanel-issime, Chanel-ed, Chanels, and Chanel-ized’, PLEASE DON’T. Our lawyers positively detest them. We take our trademark seriously.” The bottom line: Chanel did not want others using its trademark-protected name to refer to others’ goods.

As indicated by the recent Celine review, Chanel’s pleas have not deterred the fashion press from using the term to describe a certain style of jacket, namely, those made of tweed. Any why would it? As University of Oklahoma College of Law professor Sarah Burstein put it well, “There is nothing inherently wrong (or illegal) about calling a non-Chanel design ‘Chanel-like.’” Of course, she notes, that “context is key in trademark law and some uses may cross the line, but there is no per se prohibition against [the] types of uses” that Chanel sets out, such as “Chanel style, Chanel-esque, Chanel-like, Chanel-ish,” etc.

In an editorial context, it is difficult to imagine how such use would ever cross the line. However, when it comes to commercial uses, such as competing products, the potential for infringement may be greater.