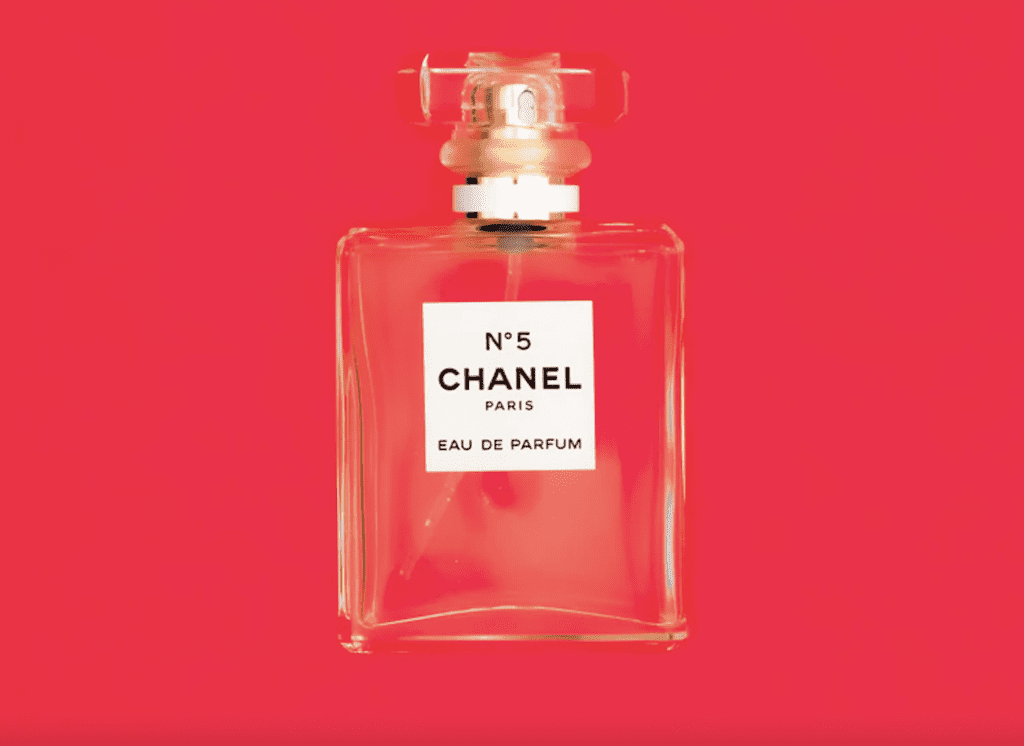

Chanel has prevailed in a lawsuit in China over the sale of a lookalike fragrance that is being marketed under the name N°9, in a case that provides some meaningful takeaways for brands looking to enforce their rights in the Chinese market. The case got its start when Chanel filed suit against perfume-maker Yiwu Story of Love Cosmetics Co., Ltd. (“Yiwu”) in the Intermediate People’s Court of Shaanxi Province on the basis that the Shanghai-headquartered cosmetics company replicated the branding of its N°5 perfume in violation of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law of China.

At the heart of the recently-decided Chanel case, which was initiated by Chanel in 2019 and first reported by IPKat, is Article 6(1) of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law of China (2019 Amendment), which prohibits parties from offering up products that are confusingly similar to those of others, including by way of “a label [that is] identical or similar to the name, packaging or decoration … with certain influence.”

Siding with Chanel back in 2020, the trial court determined that the N°5 fragrance and its packaging – namely, Yiwu’s use (and placement) of N°9, “FLOWER OF STORY,” and “Eau de Parfum” in black text on a square white label – meet the “certain influence” standard. In other words, they have “reached the distinctive level to distinguish the source of the [product] among the relevant public in China.” Moreover, the court found that the defendants’ perfume label was notably similar to Chanel’s, thereby, giving rise to a likelihood that consumers would associate the N°9 product with Chanel even though no such association exists between the two companies. Against this background, the lower court sided with Chanel, ordering Yiwu to cease its sale of the N°9 fragrance at issue and pay CNY 600,000 ($94,238) in damages and expenses to Chanel.

Fast forward to 2021, and Yiwu appealed to the Shaanxi Provincial Higher People’s Court, arguing that “neither Chanel’s N°5 perfume trade dress nor its [labeling] are distinctive enough to identify the source of the product.” In reality, Yiwu asserted that consumers identify the Chanel fragrance thanks to the brand’s use of the “N°5” and “CHANEL” marks that appear within the label on the bottle and not just by the plain bottle, itself.

Even if Chanel’s perfume bottle and labeling (sans any Chanel word marks or logos) were distinctive enough to act as trademarks, Yiwu argued that consumers are not likely to be confused because of the “significant differences [between] the consumer groups” for its products and Chanel’s, and the level of attention paid by such consumers in connection with their purchasing of fragrance products. The defendant also noted the different prices of the two parties’ products: Chanel’s N°5 retails for 61 times more than the N°9 fragrance.

In a decision handed down in January, the Shaanxi Provincial Higher People’s Court agreed with Yiwu’s argument that based on evidence, including labeling for other brands’ fragrances, “the design of the black frame on a white background [on Chanel’s labeling] is a common decoration for perfume packaging.” The court also found that the positioning/arrangement of the text within the label “is also the usual way of general packaging.”

However, the court, nonetheless, sided with Chanel as a result of Yiwu’s use of “identical or visually basically undifferentiated commodity names, packaging and decorations” on its product, which Article 4(3) of the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Some Issues Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Civil Cases Involving Unfair Competition states “shall be deemed as ‘sufficient to cause confusion (with another’s well-known commodity).’”

In dismissing Yiwu’s appeal, the court stated that when it comes to perfumes as luxury goods, “the bottle itself is a commercial sign to distinguish the source of the goods, [and] some copycat products are very similar in packaging to luxury packaging through deliberate imitation to attract consumers,” thereby, creating “hazards, such as disrupting the market order and damaging the image of large brands, and this behavior should be regulated.”

THE TAKEAWAY: Reflecting on the outcome, Tian Lu, a Ph.D. candidate in International and European Law at Maastricht University, states that the case “demonstrates how unfair competition law catches and regulates an area not easily reachable by trademark law: the look-alike or complete copycat [product] that deliberately [lacks the use of] infringing marks.” As for the extra remarks added by the Shaanxi Provincial Higher People’s Court about the harms that follow from products like Yiwu’s, Lu notes that they “make for a straightforward standpoint: [there is] very little room, if any, that the law in China has left for such copycats.”