Chanel has been handed a loss in the latest round of its bid to block registration of a stylized “m5” trademark in Europe. In a recent decision, the Fifth Board of Appeal of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”) dismissed Chanel’s appeal, finding no likelihood of confusion between Chanel’s iconic “N°5” trademark and another number 5-centric mark being used by Simb d.o.o., a Slovenian cosmetics company. The ruling signals the continued challenge brands face in enforcing single-character trademarks – especially when used in stylized or abstract form – without robust evidence of acquired distinctiveness.

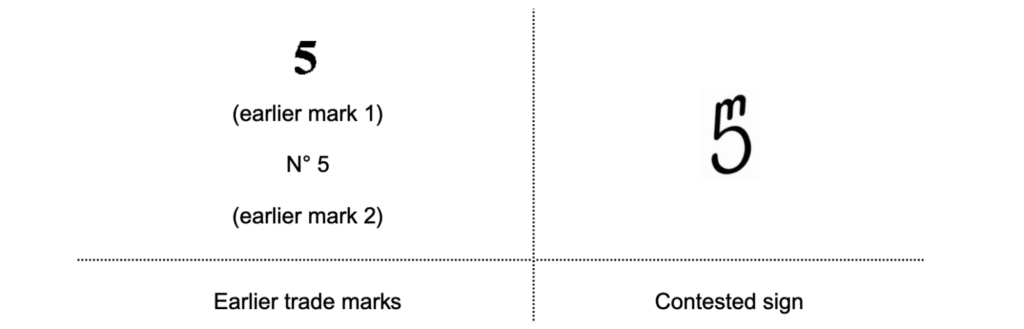

The Background in Brief: In May 2023, Simb filed an application to register a figurative trademark comprised of a stylized combination of the letter “m” (or possibly “n”) and the number “5” for use on a broad array of goods in Class 3 – from nail polish and lotions to serums and bath products. Chanel opposed the application in September 2023, arguing that consumers were likely to confuse its French-registered trademarks for “5” (figurative) and “N°5” (word mark), which are registered for use on fragrances and cosmetics, and Simb’s mark.

On the heels of the EUIPO’s Opposition Division rejecting its opposition attempt in June 2024, Chanel appealed, arguing that it maintains an “exceptional reputation” in France, and it has a long-standing association of the number “5” thanks to its flagship fragrance, and submitting additional evidence of the widespread fame and use of the “N°5” trademark.

A Graphic Twist That Consumers Will Notice

In a decision on March 20, the EUIPO’s Board of Appeal sided with Simb. Central to its reasoning: The unique graphic structure of the contested “m5” sign. The Board held that consumers would not view the “m5” mark as merely a stylized “5,” but as a distinctive and unusual fusion of a letter and a number. This design element, the Board concluded, was enough to render the sign visually and conceptually distinct from Chanel’s “N°5.”

The Board also rejected Chanel’s argument that the contested sign would be seen as either the letter “n” or “m” joined with a “5,” both of which would recall its earlier marks. Even under Chanel’s own “best-case scenario” – wherein consumers read the stylized element as “n5” – the Board found that the lack of the degree symbol “°” (which connotes “number”) and the unusual configuration of the elements differentiated the marks.

Chanel’s claim of enhanced distinctiveness through reputation also fell short. While the brand submitted a voluminous mix of brochures, press clippings, celebrity campaigns, exhibition materials, and even postage stamps, the Board held that much of the evidence was outdated, lacked territorial specificity, or failed to prove how many consumers were actually exposed to the marks in France at the relevant time. Crucially, the Board reiterated that a mark’s fame cannot be presumed, even for brands as storied as Chanel. Citing settled case law, the Board held that the reputation of “N°5” must be substantiated with current, relevant, and geographically grounded proof – something Chanel failed to provide to the requisite standard. The submission of a Wikipedia page and vintage advertisements, for example, was not enough to establish distinctiveness acquired through use.

Chanel also claimed it owns a “family” of marks built around the number 5. But here again, the evidence didn’t support the claim. The Board noted that Chanel had only cited two registered marks – “5” and “N°5” – and failed to provide sufficient proof that these marks were being used as a family in connection with the contested cosmetics. Without such evidence, the claim of a “series” of related 5-themed marks was dismissed.

The decision aligns with a growing body of case law indicating that simple numerical or typographical elements, particularly when used in a stylized or abstract way, are unlikely to support a finding of confusion unless a high bar for acquired distinctiveness is met. The ruling echoes past decisions against brands such as adidas and Louis Vuitton, where the EUIPO and EU courts have held that minimalist or geometric motifs (like stripes or checkerboards) often fail to qualify for protection absent robust, pan-EU consumer recognition.

THE TAKEAWAY: The EUIPO Board’s decision reinforces the message that legacy alone will not shield a mark from scrutiny. For companies looking to enforce rights in minimalist signs – like numerals, letters, or abstract motifs – relying on reputation requires contemporary and compelling evidence across the relevant territory. The EUIPO is unlikely to be swayed by history or aesthetic prestige alone.

Chanel retains the right to challenge the decision before the General Court of the European Union, but for now, Simb’s “m5” trademark moves one step closer to registration.