Taking Chanel buttons from the brand’s garments and refashioning them into jewelry runs afoul of trademark law. That is what Chanel argues in a newly-filed complaint, in which it accuses accessories company Shiver + Duke of “misappropriating” its “world famous and federally registered” interlocking “C” monogram trademark and its “Chanel” word mark in order to “create and market costume jewelry that draws and relies on the selling power and fame of the Chanel marks.”

According to the complaint that it filed in a New York federal court on February 12, Chanel alleges that Atlanta, Georgia-based Shiver + Duke, which describes itself as a “handcrafted modern sophisticated accessory line,” and its founder, jewelry designer Edith Anne Hunt (the “defendants”) are taking authentic “buttons bearing the CC monogram that are not intended for use other than on Chanel’s authorized clothing” and putting them on chains, earrings, and bracelets, which they then offer up for sale for upwards of $100. In promoting and marketing the jewelry on the shiverandduke.com e-commerce website, alongside jewelry that is made from Louis Vuitton and Gucci hardware, buttons, and canvas, the defendants “refer to the jewelry as ‘designer’ and in some instances, have used the CHANEL mark to identify their CC monogram button jewelry,” Chanel asserts.

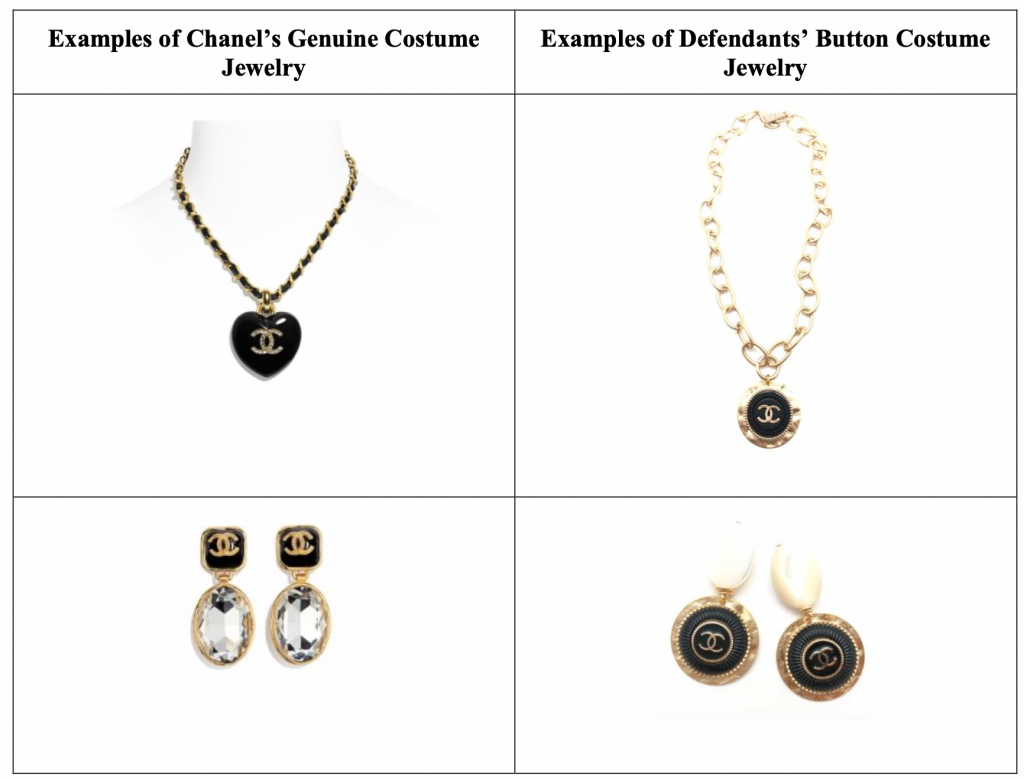

“There is no dispute,” Chanel argues, that the defendants’ “use of the CC monogram is intended to trade on the goodwill that Chanel has created in its mark through decades of use and millions of dollars in investments.” At the same time, the famed luxury brand claims that the defendants’ jewelry “does not alter the CC monogram and the jewelry nowhere states that it was created by [the] defendants without the authorization of Chanel.” Instead, the appearance of the CC monogram on the defendants’ jewelry is “no different from the display of the CC monogram on authorized Chanel costume jewelry, and to a consumer there is no distinguishable difference between the appearance of [the] defendants’ unauthorized product and Chanel’s genuine product.”

And in case that is not enough, Chanel – which says that it generated “revenue from sales of costume jewelry sold under and/or bearing the CHANEL marks from 2015 to 2019 [that] exceeded $300 million” – claims that third-party retailers that have purchased Shiver + Duke’s jewelry “have advertised and promoted the products as Chanel costume jewelry” due to the defendants’ “prominent use of the CHANEL marks” on such jewelry.

Upon discovering Shiver + Duke’s offerings, Chanel says that its counsel sent the company a cease and desist letter in September 2020, but in lieu of halting their allegedly infringing activity, Chanel claims that Shiver + Duke has “made minor changes to their products and packaging.” For instance, new product packaging that describes Shiver + Duke’s jewelry as “Reimagined” and “Reworked,” and states that the jewelry is an “original design” of Shiver + Duke that is “made from authentic buttons.”

In terms of the products, themselves, Chanel asserts that Shiver + Duke “have also added SD SHIVER + DUKE markings on the backs of the CC monogram buttons.”

Such modifications “do nothing to prevent consumers from mistakenly believing that the defendants’ jewelry originates from or is authorized by Chanel” because the “packaging still does not state that the jewelry is not authorized by or associated with Chanel, and the jewelry in the post-sale context conveys only that it comes from Chanel when it does not.” Chanel further claims that in response to its objections, Shiver + Duke “have added a small tag displaying the marking ‘SD’ to their button jewelry,” but “such use is not consistent across the product line.” And even when “the tag is used, it does not negate the primary visual focus of the defendant’s jewelry, namely Chanel’s CC monogram,” and such a tag “does nothing to inform the public that the product was repackaged and repurposed by the defendants without the authorization of Chanel.”

“Regardless whether [they] use disclaimers, tags or markings to designate [Shiver + Duke] as the manufacturer of the costume jewelry bearing Chanel’s immediately recognizable CC Monogram, in the post-sale context, the mark most prominently displayed on the defendants’ jewelry belongs to and identifies Chanel as the source of the defendants’ products,” according to Chanel. “Further, the defendants’ use of additional [Shiver + Duke] markings does not change the fact that the main source identifying feature of the costume jewelry is the CC monogram, that the jewelry is similar to Chanel’s actual products bearing the CC monogram, and that the selling power of the defendants’ products is based on the fame of the CC monogram.”

With the foregoing in mind and given the defendants’ allegedly “deliberate intent to ride on the fame and goodwill of Chanel’s trademarks, to profit from the CHANEL marks, and to create a false impression as to the source or sponsorship of the defendants’ goods or to otherwise compete unfairly with Chanel,” Chanel sets out claims of federal and state law trademark infringement and dilution, and unfair competition against Shiver + Duke and Hunt. In addition to potentially causing confusion among consumers as to the source of the allegedly infringing jewelry and “diluting or likely to dilute Chanel’s famous CHANEL marks by harming the reputation of the marks, thereby damaging the good reputation of Chanel and the CHANEL marks,” Chanel argues that the defendants’ “use of the CHANEL marks unfairly and unlawfully wrests from Chanel control over its trademarks and reputation.”

Chanel is seeking monetary damages, as well as injunctive relief to immediately and permanently bar the defendants from making, marketing, and selling the jewelry – or more broadly, using the Chanel trademark “or any simulation, reproduction, copy, colorable imitation or confusingly similar variation of the CHANEL marks.”

The case is the latest in a long line of legal actions initiated by luxury brands that have sought to exert control over distribution of goods post-first sale, including by preventing the sale of modified but otherwise authentic goods bearing their trademarks (the Rolex v. La Californienne case, for example, comes to mind) – or here, trademark-bearing parts derived from authentic goods – on the basis that such unauthorized use is both likely to mislead consumers and to cause damage to the brand.

These cases raise some interesting questions about the bounds of a trademark holder’s rights when it comes to the burgeoning resale market, as well as the role of the First Sale Doctrine, a trademark tenet that generally holds that once a trademark owner, such as Chanel, releases its goods into the market, it cannot prevent the subsequent re-sale of those goods by their purchasers. Put another way, the First Sale Doctrine enables the purchaser of a trademark-bearing product to resell that product – and/or potentially parts of it? – without facing trademark infringement liability.

A successful First Sale Doctrine argument assumes that the subsequently-resold product is not “materially different” from the original, which is, of course, a particularly relevant consideration in cases like this one. (As Seton Hall Law’s David Barnes previously noted in an article on the doctrine, when a trademark-bearing product “has been modified by its buyer is in some way marketed to third parties, however, there is potential for consumer confusion about the source of the good and the article’s qualities and characteristics,” which seems pertinent in the case at hand. “This creates a conflict between the first sale rule, which encourages competition between new and used or modified products, and trademark law’s goal of preventing consumers from being misled.”)

As for the policy concerns behind brands’ enduring attempts to police the use/sale of their products in a post-sale capacity, Yvette Joy Liebesman and Benjamin Wilson wrote an interesting article several years ago, entitled, “The Mark of a Resold Good,” in which they state that “encouraged by the expansion of trademark protection in the courts, mark owners have become increasingly aggressive in policing their marks, often relying on spurious claims of trademark infringement.” They assert that “policies that advance the mark owner’s ability to control all distribution channels would harm consumers and disincentivize competition; manufacturers would have less motivation to innovate and improve their product when they control all distribution of goods beyond their first sale.”

Ultimately, if the case at hand sounds familiar, it may be because Chanel was embroiled in a similar suit back in 2013, albeit instead of filing suit, the alleged infringer beat Chanel to court. A company called Button Jewelry by Val Colbert, faced with threats of litigation from Chanel over its button jewelry, initiated a declaratory judgment action, asking the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia to declare that it was not running afoul of trademark law by taking authentic Chanel buttons and turning them into accessories. Although, that case ultimately proven to be less-than-informative, as it quietly settled within a matter of weeks of it being filed, with the parties seemingly coming to a confidential settlement behind the scenes, and Colbert scraping her site of all Chanel-branded goods.

*The case is Chanel, Inc. v. Shiver and Duke, LLC, et al., 1:21-cv-01277 (SDNY).