Roughly 100 years after it was first released, Chanel is seeking to register the shape of the bottle its No. 5 fragrance as a trademark in the U.S. – and is facing some (unsurprising) preliminary pushback in doing so. On the heels of filing an application with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office late last year for a trademark that consists of “a rectangular shaped container with beveled sides, a thinner neck and on top a horizontal rectangular faceted shape” for use on “cosmetics; fragrances and perfumery,” an examining attorney for the trademark office has refused to register the mark, stating that the applied-for mark is not inherently distinctive because “the shape of the perfume bottle and the bottle stopper is a basic shape that is common in the fields of cosmetics, fragrances, [and] perfumery.”

Specifically, USPTO examining attorney Sabrina Tomlinson stated in a non-final Office action on August 15 that registration for the blank bottle design is refused (for now) because “the mark consists of a nondistinctive configuration of packaging for the goods that is not registrable on the Principal Register without sufficient proof of acquired distinctiveness.” Tomlinson asserted in the Office action that the bottle is “a common rectangular shaped container with beveled sides that is meant to be filled with perfume,” pointing to examples of “large, well-known retailers,” such as Macy’s, Sephora, and Ulta, that carry “many comparable and well-known cosmetics and perfumery brands that use the same rectangular shaped container with beveled sides as the base of the perfume bottle.”

“The shape is a common or basic shape that is not unique or unusual in the fields of cosmetics, fragrances, perfumery, and eau de parfum,” per Tomlinson, who notes that “although the simple rectangular shape of a perfume bottle container is relatively ubiquitous for perfume bottle shapes, the beveled sides of applicant’s configuration do not establish distinctiveness because it is a mere refinement of a commonly-adopted and well-known rectangle shape for perfume bottles that is regularly viewed by the public as the standard form for perfume bottles.”

She further asserts that the mark is “incapable of creating a commercial impression because [Chanel] has no distinctive accompanying words with the rectangular shaped perfume bottle container,” and so, “without additional and specific evidence of acquired distinctiveness, the applied-for configuration mark must be refused registration.”

Given that “the entire applied-for mark must be analyzed,” Tomlinson turns her attention to the “horizontal, rectangular faceted bottle stopper,” which Chanel claims as part of the mark. While Chanel’s bottle stopper is “faceted like a gemstone, like the bottle stoppers from Tory Burch, Versace, Kayali, and Tiffany & Co.,” it is still just a “mere refinement of a commonly-adopted and well-known horizontal, rectangular bottle stopper shape for perfume bottles that is regularly viewed by the public as a standard form of perfume bottle tops or stoppers.” As such, Tomlinson contends that without specific evidence of acquired distinctiveness, the top portion of the applied-for configuration mark must also be refused registration.

Against this background (and given that this is a non-final action), Tomlinson states that Chanel may respond by providing evidence of acquired distinctiveness in the form of “verified statements of long-term use, advertising and sales expenditures, examples of advertising, affidavits and declarations of consumers, and customer surveys. (She is also requesting that Chanel provide additional information about the mark, including (but not limited to) “a written explanation and any evidence as to whether there are alternative designs available for the feature(s) embodied in the applied-for mark, and whether such alternative designs are equally efficient and/or competitive.”)

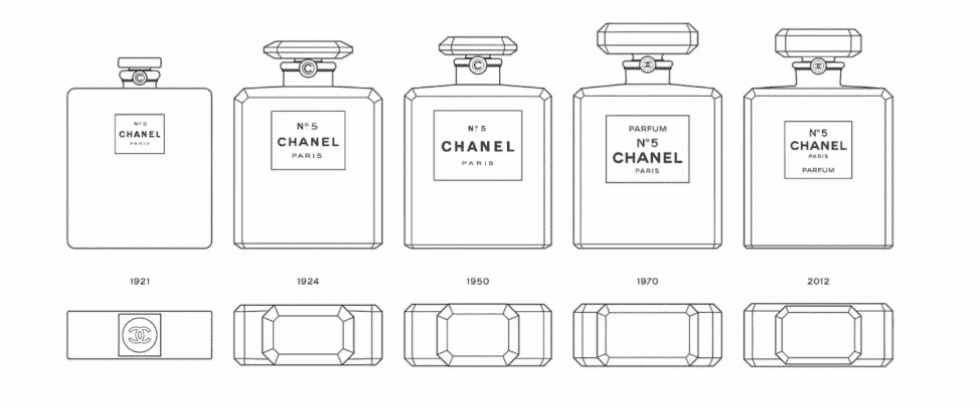

Proving secondary meaning should not be difficult for Chanel in some regards, as it has consistently made use of the bottle in its latest form since 2012. More fundamentally, Chanel No. 5, itself, is considered one of the world’s most famous and “top-selling perfumes,” according to the FT, “paving the way for the house’s broader fragrance and beauty division, which today accounts for around one third of the house’s $12.27 billion [in] annual revenue.” At the same time, the famed fashion brand has extensively advertised the fragrance – packaging, included – by way of ad campaigns. To put its No. 5-specific ad spend into perspective, Chanel reportedly spent an estimated $17 million on a commercial and print ad for Chanel No. 5 featuring Brad Pitt back in 2012 and is said to have shelled out as much as £18 million on a two-minute commercial for the fragrance starring Nicole Kidman in 2004.

Also on Chanel’s side: It has already been able to convince the USPTO to register the shape of the bottle (and has since enforced that mark via infringement litigation). The registration, which was initially registered in 2000 for use on perfume in Class 3, was renewed in 2020.

While “few fragrances – or objects, for that matter – carry as much symbolism as Chanel No 5,” Vivienne Becker wrote for the FT last year, one place where the brand could potentially face issues is whether consumers link the shape of the bottle, on its own, with a single source. After all, Chanel does not appear to use the bottle on its own, i.e., without some other forms of Chanel branding, such as the Chanel word mark, No. 5 mark, or its interlocking “C” logo. That is not likely to be an issue now, as Chanel and other brands have been able to register the shape of their perfume bottles sans any other branding elements.

Chanel, for one, boasts a U.S. registration for its cylindrically-shaped Chance fragrance bottle – sans any other branding elements, and Beaute Prestige International maintains a registration for the shape of a Narciso Rodriguez perfume bottle, which it describes as “a distinctively designed perfume bottle which comprises a unitary combination of a colored interior and a T-shaped top of the same color, to create the impression of a bottle within a bottle” – just to name a couple of examples. (These registrations are distinct from – and potentially much broader than – registrations that Saint Laurent, for example, has amassed for its Opium fragrance bottle, in which the mark is described as “the configuration of a distinctive fragrance bottle made from colored glass, and the atomizer and cap therefor,” including the use of “the wording ‘OPIUM’ and ‘YVES SAINT LAURENT.’”)

The existence of USPTO registrations – which Chanel will almost certainly amass for its No. 5 bottle (which is already has rights in) – does not, however, mean that these blank-bottle marks could not come under fire in the event that the brand attempts to enforce its mark against an alleged infringer, who could argue (in an attempt to escape infringement liability) that the brand does not actually enjoy such expansive rights, as it exclusively makes use of the bottle with its name on it, making it so that consumers do not link the bottle shape, on its own, to a single source.

Chanel’s application for registration for the No. 5 bottle shape comes as the company is also seeking a registration for the number 5 for use on cosmetics in furtherance of a larger trend of brands seemingly looking to bolster their rights in – or better yet, their registrations for – some of their most famous indicators of source.