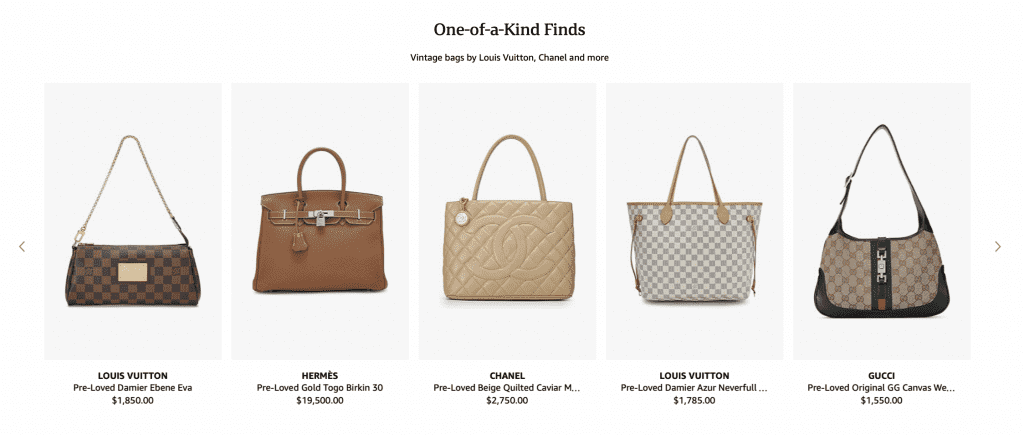

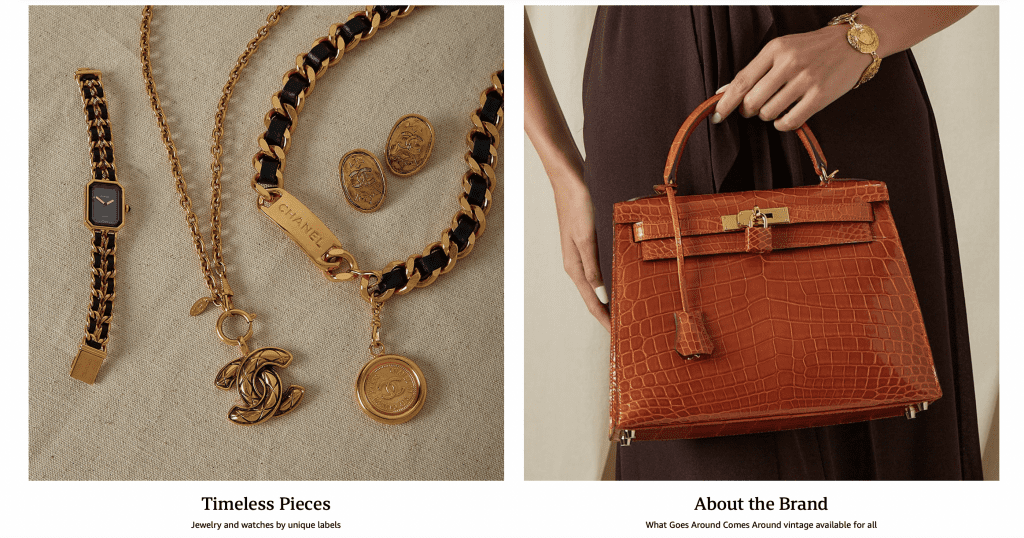

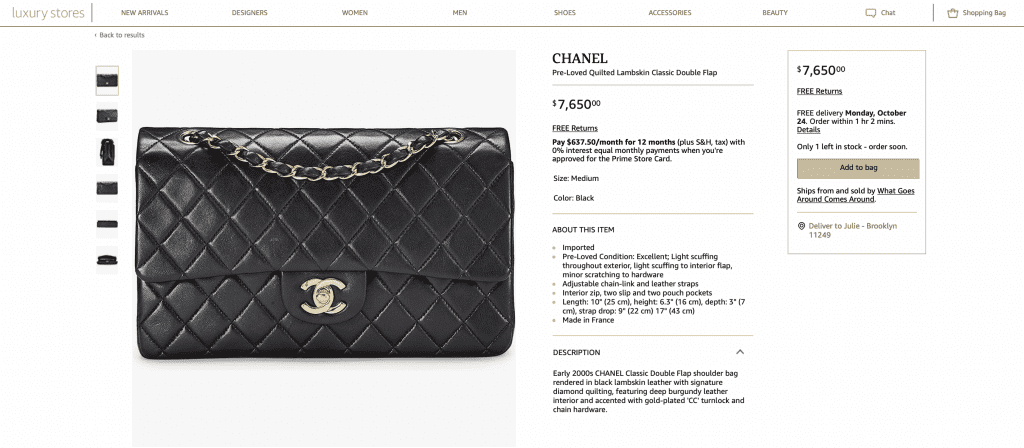

Two years after Amazon first announced the launch of its Luxury Stores venture, big-name luxury brands’ offerings – i.e., those of Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Rolex, and co. – are coming to the heavily-trafficked e-commerce platform. Unsurprisingly, things like Louis Vuitton bags and Rolex watches are not being stocked on the Jeff Bezos-founded platform by way of the brands, themselves. Instead, a partnership between Amazon and reseller What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”), which boasts its own storefront on Amazon as of Thursday, means that consumers can snap up an expanding selection of pre-owned luxury goods, from Chanel, Hermès, Louis Vuitton, Gucci, and Dior bags to Chanel jewelry, Hermès scarves, and a handful of Rolex watches via Amazon’s site.

The debut of WGACA on Amazon’s Luxury Stores – which follows from an already-existing tie-up between the established reseller and Amazon-owned Shopbop that results in a limited number of luxury goods listings on Amazon’s marketplace – is likely to prompt ire from the notoriously controlling luxury brands whose wares are being hawked without their involvement or authorization.

Top of mind is the potential for these brands to take issue with their trademark-bearing goods being marketed and sold alongside the stream of counterfeit and otherwise infringing goods that are readily available on Amazon’s main marketplace site. Chanel, for one, argued in its since-settled lawsuit against Crepslocker that the British reseller’s unauthorized use of Chanel trademarks alongside “other brands, which do not have similar associations of luxury, prestige, exclusivity and longevity to those enjoyed by [Chanel],” was problematic. (And there were not even counterfeit goods at play in that case.)

The offering up of authentic goods without a brand’s authorization after the goods are first released into the market by the trademark-holding brand is protected from infringement liability under the first sale doctrine. (It is well-settled that “the right of a producer to control distribution of its trademarked product does not extend beyond the first sale of the product,” in the words of the 10th Circuit.) Nonetheless, it is difficult not to wonder whether the brands whose wares are now being displayed on Amazon via WGACA still have some valid arguments to make, especially given existence of counterfeit and/or infringing luxury goods (like fake Gucci bags, fake Prada bags, Chanel knockoffs, and fake Dior bags) on Amazon’s site, which has almost certainly ruled out any possibility of most luxury brands partnering with it.

The most immediate exception to the first sale doctrine is when the goods at issue are “materially different” from those sold by a brand and/or its authorized sellers. This does not seem to apply on its face, as the products here, including Chanel flap bags, three Hermès Kelly bags, the long list of Dior Lady bags, etc., do not appear to be materially different than they were at the point of initial sale.

Not the Goods, But the Conditions

However, another exception to the first sale doctrine exists beyond the offering up of materially different goods, and applies in instances in which an unauthorized seller is reselling trademark-bearing products that are outside of the trademark owner’s quality controls – or in other words, the conditions of the sale are different. For this exception to apply, a trademark holder must show that: (1) it has established quality control procedures that are legitimate, substantial, and not pretextual; (2) it abides by its quality control procedures; and (3) the unauthorized seller is not abiding by the procedures and its sales of non-conforming products will harm the value of the trademark and create a likelihood of consumer confusion.

This would not be a tough argument for luxury brands like Louis Vuitton and co. to make. In fact, we saw this in the Crepslocker case, in which Chanel argued that it maintains stringent requirements governing “the location, interior arrangement, and signage of the store from which the goods will be sold,” staff training, “point of sale guidelines,” and “quality standards in relation to marketing, including appropriate brand adjacencies,” among other things, none of which were being observed by Crepslocker in connection with its sale of otherwise authentic Chanel-branded products.

Specifically, Chanel took issue with Crepslocker’s packaging, its requirement that consumers pay via PayPal (and not credit card), its no-return policy for items that had been specifically sourced for individual customers, its price premiums for items, and the alleged unavailability of authentication cards for certain Chanel bags. Taken together, these factors resulted in Crepslocker offering “a service that is materially worse” than what Chanel and its authorized retailers provide, and thus, damaging the Chanel brand. (That case settled before the court could provide any insight.)

More recently, the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado shed light on quality control exception to the first sale doctrine in a case over the unauthorized sale of Otter brand cell phone and tablet cases online, including on Amazon’s marketplace. Otter filed suit against Triplenet, arguing that the reseller’s distribution did not meet the quality control standards observed by the company and its authorized resellers, such as conditions that applied to shipping, product inspection, removal and reporting of damaged goods, and product display.

Siding with Otter (on a motion for partial summary judgment) in November 2021, the court held that the company established that it has legitimate quality control measures insofar as it allows its products to be sold to consumers only by it or authorized resellers, which Triplenet did not observe, and that Triplenet’s nonconforming sales diminished the value of Otter’s trademarks because such sales interfered with Otter’s ability to ensure its products adhered to its quality standards.

Potential Marketing Issues

Still yet, particularly displeased brands might try to go further and take issue with the marketing of the products being offered up by WGACA. In the still-pending lawsuit that it filed against WGACA, Chanel argued that the reseller was making “excessive” use of Chanel trademarks in an attempt to lead consumers to believe that it is in some way authorized or affiliated with Chanel. (Chanel filed suit against WGACA in March 2018, accusing the New York-based resale entity of selling “non-genuine, infringing Chanel products, and improperly us[ing] Chanel marks in its advertising and marketing.”) The strength of such an argument is questionable here, as it does not seem (to me) that WGACA and Amazon are using the brands’ marks in a manner that extends too far beyond listing/describing and displaying the available products.

Beyond that, brands might push back against the marketing of the goods here as “vintage,” as Chanel did in its case against WGACA (and still-pending lawsuit that it filed against WGACA, as well), asserting that the reseller runs afoul of the Federal Trade Commission’s advisory on the labeling of “vintage” products, which are items that are “at least 50 years old.” Per Chanel, WGACA represents “some of its Chanel-branded products to consumers as ‘vintage’ even though such items are of recent distribution and sale.” Some of its “rare vintage” Chanel bags are, according to Chanel’s complaint, “are less than twenty years old.”

It is worthing noting that with such resale-specific litigation presumably in mind (and knowing the claims that certain brands have made against resellers in the past), it is not surprising Amazon and WGACA have opted not to lean too heavily into explicit authenticity warranties. The claim that WGACA does make, which is included in the “About” section, states, “WGACA guarantees authenticity of every item through their multi-tiered authentication process. WGACA is not an authorized reseller and is not affiliated with any of the brands they sell; brands are not involved in their authentication process.”

As for whether WGACA and Amazon are concerned about legal issues, the consensus appears to be no. Amazon Fashion president Muge Erdirik Dogan told WWD that “Luxury Stores at Amazon is in regular touch with all luxury brands on various ways to collaborate with Amazon’s technology, operations, innovations and more.”

Hypothetical legal issues aside, the partnership between Amazon and WGACA is a striking one in light of Amazon’s well-established ambitions in the fashion and luxury space, and the unwillingness of top-tier fashion/luxury brands to take part. Against that background, the scenario seems like a major win for Amazon, which gets access to WGACA’s supply of pre-owned goods; if The RealReal’s costs and physical expansion is any indication, amassing high-quality supply is not an easy or inexpensive endeavor. Amazon also benefits from WGACA doing the authentication work – another cost-intensive and demanding effort. Finally, WGACA will also handle shipping for all of the goods at issue – making for what seems like the best possible scenario for Amazon given the large-scale refusal of luxury’s biggest names to play ball.

UPDATED (Sept. 20, 2022) : This article has been updated to remove a quote from WGACA.