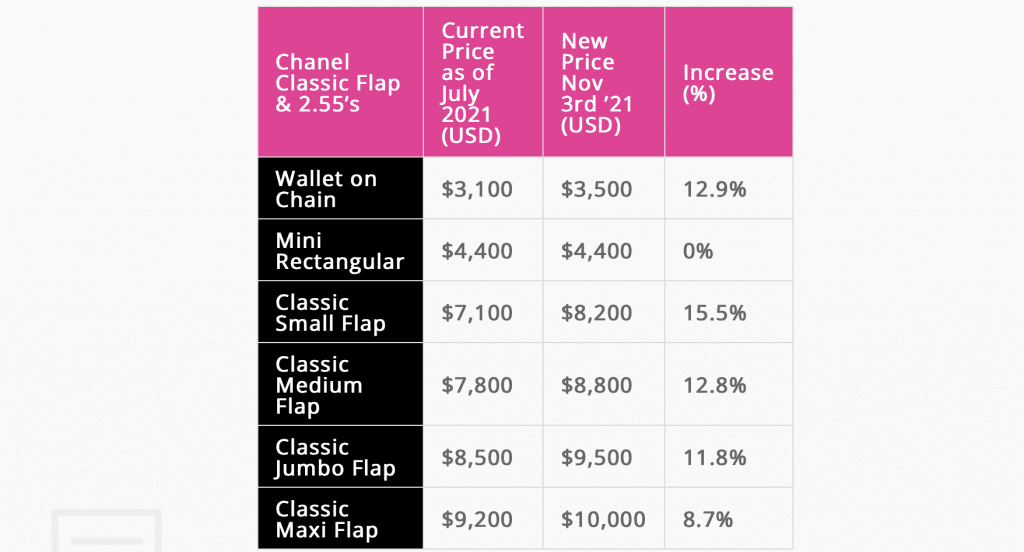

Chanel has raised prices yet again, marking its third price increase since the start of the pandemic. The French fashion house hiked up the price tags for its Classic Flap and 2.55 bags early this month by as much as 15.5 percent, sending prices of its Classic Small Flap and Classic Medium Flap bags up to $8,200 (from $7,100) and $8,800 (from $7,800), respectively, and its Jumbo and Maxi Flap at $9,500 and $10,000, thereby, putting the latter bags on par with the retail prices (as distinct, of course, from the resale prices) of certain in-demand Hermès models, such as its Birkin 25.

A spokesman for Chanel confirmed that the price increase is limited to the brand’s “iconic models, namely the Timeless Classic and the 2.55.” The representative also noted that “like all major luxury brands, Chanel regularly adjusts prices to take into account changes in our production costs and raw material prices, as well as exchange rate fluctuations,” a nod to attempts by a growing number of brands to crack down on price arbitrage and the gray market.

The price boosts come amid a larger string of changes at Chanel in furtherance of a push that appears to be focused on enhancing exclusivity and addressing the burgeoning resale market for its increasingly-expensive bags. Among a number of new initiatives that have been rolled out by Chanel is a new policy – currently in place in the Korean market, at least – that places limits on the number of bags that customers can purchase per year. Specifically, the Korea Times reported this fall that as part of a new policy, “Each customer can buy one Timeless Classic flap bag and one Coco Handle bag per year.” Similar quotas also exist for small leather goods, including wallets and pouches, assuming that “a customer wants more than one of the same model in the category.”

As TFL previously noted, Chanel is not the only brand placing strict limits on the sale of certain products; it joins the likes of Hermès, which has notoriously restricted the quantities that consumers can purchase of certain “quota” bags, namely, Birkin and Kelly bags, to two bags per a calendar year in furtherance of a “very limited distribution strategy.” At the same time, Rolex has reportedly been “restricting per-capita purchases” in the Korean market in light of raging demand and limited supply. Dating back further, Louis Vuitton has been known to curb the ability of consumers to purchase more than two of each handbag style per calendar year in an attempt to put a halt to “professional buyers” who were purchasing and then reselling luxury goods “through small shops throughout Asia, or through online retailers like eBay,” the New York Times reported back in 2008.

The aim for Chanel is largely the same: it is working overtime to ensure that its hard-earned luxury positioning (and its margins) remains intact and not at the mercy of the burgeoning resale market, where it has no control over the products being offered up, the condition of those goods, and the manner in which they are marketed and sold, hence, its rocky relationship with the segment.

Beyond quotas, Chanel has also revamped its warranty program, extending it from a mere one year to five years for customers that buy bags, as well as wallets on chain styles, from the brand, itself – again, as distinct from purchases that come by way of the resale market. TFL exclusively reported this summer that Chanel has been quietly filing a handful of trademark applications for registration in the U.S. (and beyond) that shed light on its ambitions in the space. Dating back to late last year, for instance, Chanel filed to register “Chanel & Moi,” as well as its famous word mark and double “C” logo for use on “cleaning and repair of fashion and fashion accessories.” It has filed additional applications for registration for similar goods/services for marks like “Ready to Care” and “La Sirene.”

All the while, in addition to announcing the terms of its new warranty program this spring, Chanel also unveiled “CHANEL Restoring Care,” which it describes as “an array of unique care services [that] will exist in each of [its] boutiques across the world” to repair and rejuvenate certain Chanel products. “This commitment to every CHANEL creation will engage the House’s singular ecosystem that emphasizes its artisans who specialize in restoration and repairs,” according to Chanel, which further asserts that the artisans’ “expertise and dedication showcase a seasoned savoir-faire that is deftly achieved in the CHANEL ateliers that are fabled for having every material and element at hand.”

By offering up these services, especially as it continues to raise prices (quite aggressively in some cases), Chanel is essentially providing consumers with additional value in connection with their purchases, a move that stands to engender goodwill for the brand and strengthen its bond with existing customers, while helping it to attract new ones. At the same time, these moves – including the attempt to rein in buying that is done purely for the purpose of resale (by way of the quota system), as well as Chanel’s recent swapping out of its authentication cards for technology-linked authentication plates – are also significant in that they appear to be the latest effort by Chanel (and others, of course) to limit the sale of their products exclusively to authorized distributors, as opposed to allowing them to slip into the luxury resale market.

Ultimately, the overarching effort here by Chanel seems to see it angling to align its model more closely with that of Hermès, which maintains a relatively tight hold on – and enjoys cult-like demand for – its most coveted offerings, and less like other luxury counterparts like Louis Vuitton and co., which depend, in large part, on higher turnover of their handbags and other accessories. (That is not to say that Hermès is immune from the impact of the resale market, and in fact, is looking to limit purchases for commercial purposes, as indicated by language added to its sales receipts and website terms.)

The apparent similarity between Chanel’s budding strategy and the time-tested Hermès model has not been lost on those close to the brand. Handbag news site PurseBop reported last week that at least one Chanel sales associate confided in the article’s author that it is, in fact, “leaning into the sales model followed by ‘another French brand.’”

As for responses to the latest price boost by the brand, they are proving to be mixed yet again. Following reports that price tag hikes were in the works, Korea Times reported this week that “hundreds of shoppers had lined up in the Chanel stores of major department stores from early morning to get the bag before the price increase was [rumored] to take effect,” with the publication also noting that existence of “complaints in online forums that Chanel considers Korean consumers pushovers who continue to purchase the company’s luxury goods.” Meanwhile, at least some industry experts have questioned the approach, suggesting that consumers may ultimately become dissuaded by “constant increases” and view them as something of “an insult and a form of disrespect, especially considering the incredibly high margins these products already have for luxury brands.”