From lawsuits over the unauthorized use of others’ imagery by brands like Volvo and famous figures like Emily Ratajkowski, and ongoing litigation centering on whether cosmetics giant Coty and hipster retailer Urban Outfitters misappropriated trade secrets in the course of M&A discussions (in Coty’s cases, this discussions resulted in headline-making deals with Kylie Jenner’s Kylie Cosmetics and Kim Kardashian’s KKW brand) to the enduring fights that Chanel has waged against players in the burgeoning resale market, there are an array of interesting lawsuits set to unfold further in 2021. Here is a look at a handful of the (many) cases we have our eyes on in 2021 …

1. Emily Ratajkowski Claims Instagram Post is Fair Use

Emily Ratajkowski’s “mood forever” got her sued in 2019. According to a complaint filed in a New York federal court in October 2019, photographer Robert O’Neil claims that Ratajkowski and her corporate entity Emrata Holdings LLC ran afoul of federal copyright law when the famous model posted one of his photos to her Instagram story without his authorization. Unlike the vast majority of paparazzi photo cases, this one did not swiftly run its course and end in a confidential settlement agreement, and instead, the two parties have been going back and forth in the case, which Ratajkowski’s counsel calls a “bad faith” quest for an “unsubstantiated payday.”

In one of the latest rounds, counsel for Ratajkowski has sought to have the case decided early and in her favor, arguing in a summary judgment motion in September that O’Neil failed to make his case on multiple fronts. In a subsequent filing on October 28, Ratajkowski’s counsel asserts that the paparazzi photographer’s cross-motion for summary judgment should be denied, and Ratajkowski’s motion for summary judgment – which would decide the case ahead of (and in lieu of) a trial as a result of a lack of disputed facts – should be granted.

The basis for Ratajkowski’s motion? According to Ratajkowski’s opposition to O’Neil’s cross-motion for summary judgment and reply in support of her own motion for summary judgment, counsel for the model sets the stage by asserting that O’Neil “regularly parks outside [her] home and follows her in hope that he can take her photograph without her permission, and then sell it to a third party.” That is precisely what happened last fall, Ratajkowski claims, when O’Neil took nine photos of her, one of which she subsequently posted to her Instagram story along with the caption, “mood forever.” According to Ratajkowski, her caption along with the fact that her “face is covered by a bouquet of flowers” in the photo – which appeared on her Instagram story for 24 hours – serves “to comment on her perception of the predatory nature of [O’Neil’s] practice.”

Piggybacking on the claims that she made in her motion for summary judgment, Ratajkowski argues that she is entitled to a win, as O’Neil has failed to prove “the basic elements of copyright protection,” and even if he had sufficiently proved that his photo is, in fact, subject to copyright protection, her “transformative use” of the photo constitutes fair use, thereby, shielding her from copyright infringement liability.

2. Volvo Argues that its Use of Publicly-Shared Photos is Not Infringement

In June, Jack Schroeder and Britni Sumida filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Volvo. In the complaint, which was filed in a California federal court, Schroeder, a photographer, claims that he organized a photo shoot in April 2019 that featured Sumida, a “highly sought after model,” and a Volvo S60, and was set against the background of the “super bloom” of wildflowers in the desert of Southern California. Not long after the shoot took place, Schroeder alleges that Volvo began running “a global advertising campaign” on social media “to increase sales, attract new customers, and enhance its brand goodwill.” The “campaign” – which was featured in Volvo’s Instagram Stories and on its Pinterest account – “inexplicably consisted solely of the nine photographs that [Schroeder] had posted to his Instagram account, as well as two photographs that he posted to his personal website, including images featuring Ms. Sumida.”

The problem, according to Schroeder and Sumida, is that Volvo was not affiliated with the shoot, and used the images without licensing them or otherwise receiving their authorization. With such unauthorized use of the photos in mind, Schroeder and Sumida filed suit, arguing in their copyright infringement, unfair competition, and misappropriation of likeness complaint that the car company “irreparably tarnished [them], diminishing the value of their work, and causing decreased revenue in the future.”

In response, Volvo filed a motion to dismiss in August, seeking to have the suit tossed out in its entirety on the basis that it “simply used basic social media sharing/publishing platform features to re-post” Schroeder’s images of its S60 sedan “after Schroeder and others had already published (and tagged Volvo in) the photos on their own public social media accounts.”

The crux of Volvo’s motion to dismiss: Schroeder and Sumida’s complaint overlooks critical language in Instagram’s Terms of Service. To be exact, Volvo states that pursuant to Instagram’s Terms, “whenever an Instagram user [publicly] shares, posts or uploads photos or videos, that user grants Instagram a broad, royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable license in and to that posted content … to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, [or] translate” that content and/or to “create derivative works [based on such] content.” That license, Volvo argues, is then granted to other users from Instagram in a sublicense capacity, thereby, enabling them to re-share the imagery on the app.

Judge Virginia Phillips of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California denied Volvo’s motion in September, holding that, among other things, “whether [Volvo] had a license to use Schroeder’s photographs falls outside of the allegations of the [second amended complaint] and are not facts of which the Court has taken judicial notice.” Volvo has since filed its answer to the amended complaint and set out counterclaims of trademark infringement and trademark dilution.

3. A Few Misappropriation by Acquisition Cases

Misappropriation by acquisition cases are having a moment in the fashion/beauty space. On the heels of Olaplex landing a $66 million win in the trade secret suit it filed against L’Oreal in January 2017 (less than a year after the enactment of the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act), in which the haircare startup accused the beauty titan of pilfering confidential information about its products during potential M&A discussions, three similar suits have since been filed. Le Tote sued Urban Outfitters in June, alleging that the company has stolen its trade secret-protected business model under the alleged guise of a potential acquisition in order to create a rival fashion rental business, Nuuly.

Around the very same time, Seed Beauty – the Southern California-based company responsible for “creating, developing, manufacturing, storing, selling, and distributing” the products of the billion dollar beauty ventures of Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner – filed two separate trade secret lawsuits: one against Kardashian’s KKW Beauty, and another against Coty, Inc. and Kylie Jenner’s corporate entity, in connection with Coty’s acquisitions of stakes in the half-sisters’ buzzy brands.

In both of its complaints, Seed alleges that as a result of the cutting-edge nature of its business model, the details of its “creative and logistical development services” and the terms of the “exclusive relationships [it has] with its beauty brand partners” amount to “highly sensitive, confidential and trade secret information.” Those “highly sensitive and confidential” elements of its business are at risk, Seed claims, due to Jenner and Kardashian’s respective headline-making deals with Coty.

All three cases – which raise interesting issues which may only end up growing in number in light of the enduring industry consolidation that is being born from COVID-19 and the resulting market volatility, demonstrates that “the risk for acquiring companies” or potentially acquiring companies – are still underway in the respective courts, with Urban Outfitters, for one, arguing this summer in response to the suit filed against it that “Le Tote is falsely accusing [it] of misappropriating and using unspecified ‘trade secrets’ – which Le Tote supposedly shared with [it] during those discussions – to launch Nuuly, Urban’s own fashion rental subscription business.”

“Stripped of its rhetorical flourish,” Urban argues that Le Tote’s complaint “boils down to two core contentions: (1) pursuant to a written non-disclosure agreement [“NDA”], Le Tote shared supposed ‘trade secrets’ with Urban (although the complaint never identifies a single specific trade secret disclosed to Urban), and (2) because Urban thereafter launched a business that competes with Le Tote, Urban must have misappropriated and improperly used those purported trade secrets.”

In lieu of identifying the “trade secret” information with any specificity, Urban alleges that Le Tote makes “vague references to broad areas of technology and practices within the rental clothing industry and asks the court to infer that something there must have been a trade secret, and that Urban must have misappropriated and used Le Tote’s trade secrets in order to launch a competing business notwithstanding Urban’s long-standing leadership within the retail fashion industry.”

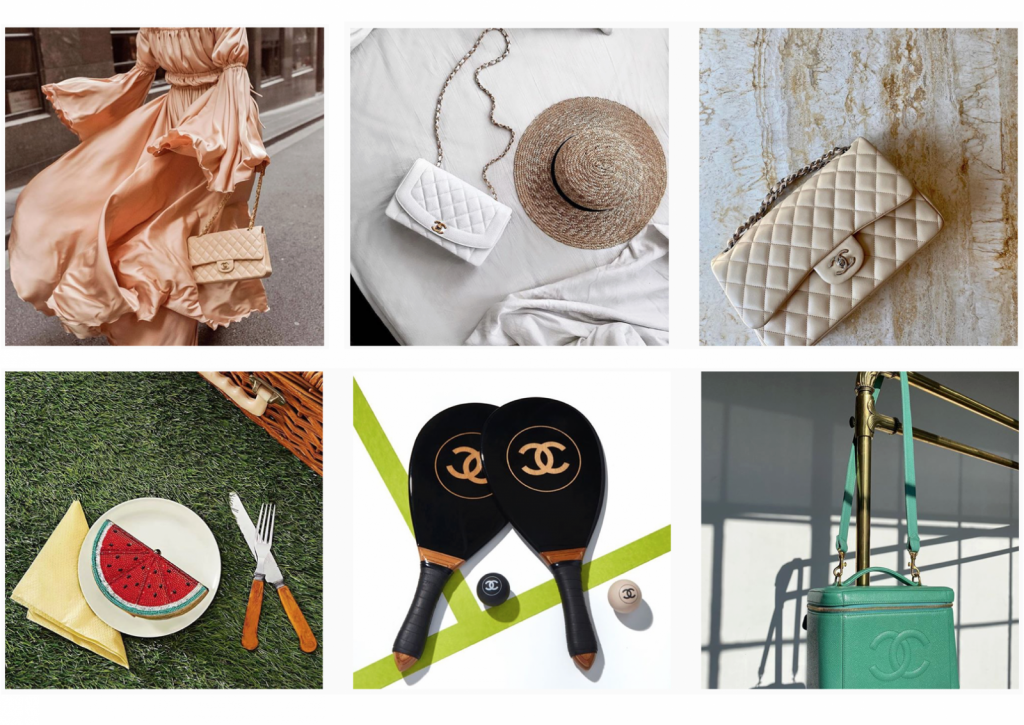

4. Resale Wars: Chanel v. The RealReal, Chanel v. What Goes Around Comes Around

The ongoing battles between Chanel and The RealReal (“TRR”), and Chanel and What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”) are still playing out in federal court, with both cases heating up in recent rounds. In late October, for instance, TRR sent a letter to Judge Gabriel Gorenstein of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District asking the court to permit it to “amend its answer to assert antitrust and related anticompetitive counterclaims” against Chanel in light of its discovery of “new evidence” about Chanel’s “motivation” in bringing various trademark-centric lawsuits against its competitors, including the one it filed against TRR in November 2018.

Along with the letter, the San Francisco-based resale company submitted a proposed amended answer and counterclaims, which follow from the allegations that Chanel made in its February 2019 amended complaint, including that TRR has engaged in trademark infringement and counterfeiting by offering up pre-owned Chanel products on its e-commerce site and in its brick-and-mortar outposts. The crux of TRR’s antitrust-centric arguments is that Chanel has been quietly carrying out an “aggressive campaign” of “exclusionary and anticompetitive conduct” aimed at “monopoliz[ing] the market” – and thus, the supply and price of its goods, both new and pre-owned – to the detriment of its competitors and consumers, alike.

Chanel has since pushed back, arguing that TRR’s attempt to lodge antitrust claims against it is a “transparent tactic … to divert attention” away from the counterfeiting claims at play, and claiming that even if TRR’s antitrust claims are not time-barred (Chanel argues that they are), the resale company has failed to adequately show that Chanel actually monopolized – or attempted to monopolize – the market, and that its tortious interference claims are similarly without merit.

As for the Chanel v. WGACA case, an interesting round was underway this summer in the midst of a discovery dispute between the parties. Despite instructions from the court that Chanel must specify with “particularity and detail” the products that WGACA sold that are not genuine; that were falsely advertised; or that were acquired under circumstances in which the first sale doctrine does not apply (in response to which WGACA would share “all documents, witness statements and arguments [in connection with those products] that it proposes to use or refer to at trial”), WGACA alleged that Chanel has failed to make good on its end of the deal.

The squabble raises the question of what products fall within the realm of counterfeit or otherwise infringing (and what constitutes infringement, more generally), with the parties clashing over whether bags that were made in authorized Chanel factories, but that “were never received by Chanel for quality control and approval” and were never they “actually sold by Chanel or any of its authorized retailers” were to be considered to be “not genuine.”

Chanel argued that some 51 bags that WGACA sold are counterfeit because they were never quality-checked, authorized, or sold by Chanel. According a July 31, 2020 letter than Chanel sent to the court, nearly “four decades of precedent” from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit establishes that, “simply put, goods that are not approved for manufacture and/or sale by the trademark owner are not genuine goods and the sale of such unapproved products gives rise to trademark infringement.” Meanwhile, WGACA called foul, arguing that a “Chanel bag made by an authorized factory does not morph into a counterfeit simply because the factory does not follow some element of a designated protocol.” In that same vein, WGACA asserts that such a claim is “hardly one that speaks to counterfeiting.”

At the same time, both TRR and WGACA have called attention to Chanel’s relationship with Farfetch, in which it maintains a minority ownership stake, and in particular, its failure to take uniform legal action against the fashion marketplace for offering up pre-owned Chanel bags in the same manner as they have. This shows that Chanel knows that they are “not engaged in wrongful conduct … and instead, has chosen to make a deal with one competitor, and attack other competitors (namely, WGACA and The RealReal) as part of a bad faith pretextual campaign to quash legitimate competition,” WGACA argued in a filing in November.

5. Models are Suing Moda Operandi, Vogue for Allegedly Using Photos of Them Without Their Permission

A group of nearly 50 models is suing Vogue’s parent company Conde Nast and fashion pre-sale site Moda Operandi for allegedly using images of them to sell high fashion garments and accessories without their permission. In a complaint filed in September, dozens of well-known models claim that both Moda Operandi and Vogue “broadly” used images of them despite knowing that their authorization was required.

According to the 87-page complaint, which was filed in a New York federal court. 44 models represented by the model management company, Next Management allege that they are professional models “who are routinely hired by companies for their modeling services to sell products,” and are all “well known in and to (at least) the modeling industry, and [their] image, identity and persona identity have been exposed and are known to the general public.” Despite being “sophisticated licensors and licensees of intellectual property and knowing that a model release is required to use a person’s name or image or likeness for trade, advertising or commercial purposes,” the plaintiffs claim that Moda Operandi and Vogue used their images on their respective websites for “trade, advertising and commercial purposes.”

The issue? At no time did either of the defendants “seek or obtain the prior written consent from any of the plaintiff(s) for the complained of uses of their images.”

Against that background, the models claim that their counsel sent cease and desist letters to Conde Nast and Moda Operandi in April 2020, but despite communications from both of the defendants, including entering into “a confidentiality agreement so that Vogue could provide certain pre-suit disclosures on a confidential basis and for settlement purposes,” the parties have not reached settlements and the photos remain on both parties’ websites.

6. Will “Bad Spaniels” Get the SCOTUS Treatment?

While Virgil Abloh’s brand Off-White is currently in the midst of a budding parody fight involving a California-based ice cream chain, another parody case may end up before the Supreme Court this year in light of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit’s decision – and Jack Daniel’s subsequently-filed cert petition – in the trademark infringement and dilution case that the whiskey-maker filed against dog toy-maker VIP Products LLC for including the trademark-protected branding of its famous whiskey to a lineup of offerings that also features bottle-shaped toys that read, “ButtWiper,” a play on Budweiser, and “Heini Sniff’n,” a take on Heineken.

By including a Jack Daniel’s play in its offerings, the spirits company claims that VIP Products hijacked its trademark and bottle design, thereby, running afoul of trademark law.

On the heels of the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona finding for Jack Daniel’s on all claims and entering a permanent injunction in its favor, VIP Products appealed, and the Ninth Circuit concluded that the Bad Spaniels toy is an expressive work entitled to First Amendment protection. In a decision from March 2020, the Ninth Circuit held that while VIP Products used Jack Daniel’s trademarks to sell its dog toys, the “humorous message” conveyed by the toy makes the use “expressive” and protected under a heightened First Amendment standard as a result.

Jack Daniel’s has since sought Supreme Court intervention, pointing to mixed treatment by lower courts of trademark infringement claims involving the use of famous marks on commercial products in a “humorous” capacity. In its September 15 certiorari petition, Jack Daniel’s asked the nation’s highest court to take on the case, and determine: (1) whether a commercial product using humor is subject to the same likelihood-of-confusion analysis applicable to other products under the Lanham Act, or must receive heightened First Amendment protection from trademark-infringement claims, where the brand owner must prove that the defendant’s use of the mark either is “not artistically relevant” or “explicitly misleads consumers,” and (2) whether a commercial product’s use of humor renders the product “noncommercial” under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(C), thus barring as a matter of law a claim of dilution by tarnishment under the Lanham Act.