On Instagram, there are currently more than 250,000 hashtags devoted to the Museum of Ice Cream and its various temporary outposts that have popped up in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Miami. The brainchild of 26-year old Maryellis Bunn – a former design consultant for Facebook – and her business partner Manish Vora, the Museum is a pop-up exhibit, complete with a sprinkle pool, a room with pink saltwater taffy-covered walls, and a mint-themed “grow room” with real mint plants, a key ingredient for mint-chocolate-chip ice cream. Selfies are encouraged and ice cream is offered all around.

Since its launch in the summer of 2016, the Museum has been met with marked demand. Its debut in New York’s Meatpacking District resulted in the sale of all 30,000 available tickets and a waiting list of more than 200,000 people. A year later, the first batch of tickets for its temporary San Francisco location sold out in 18 minutes. In a matter of just six months, that outpost attracted 600,000 visitors and announced a 3-month addition to its already-extended stay.

With such momentum in mind, the Museum’s creators have landed a deal with talent mega-agency WME, expanded to retail collaborations, and from the looks of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s (“USPTO”) records, are looking to gain exclusive rights in an array of trademarks associated with their venture, including for the Museum of Ice Cream name; flavors, such as Cherrylicious and Vanillionaire; and their marquee attraction, the Sprinkle Pool.

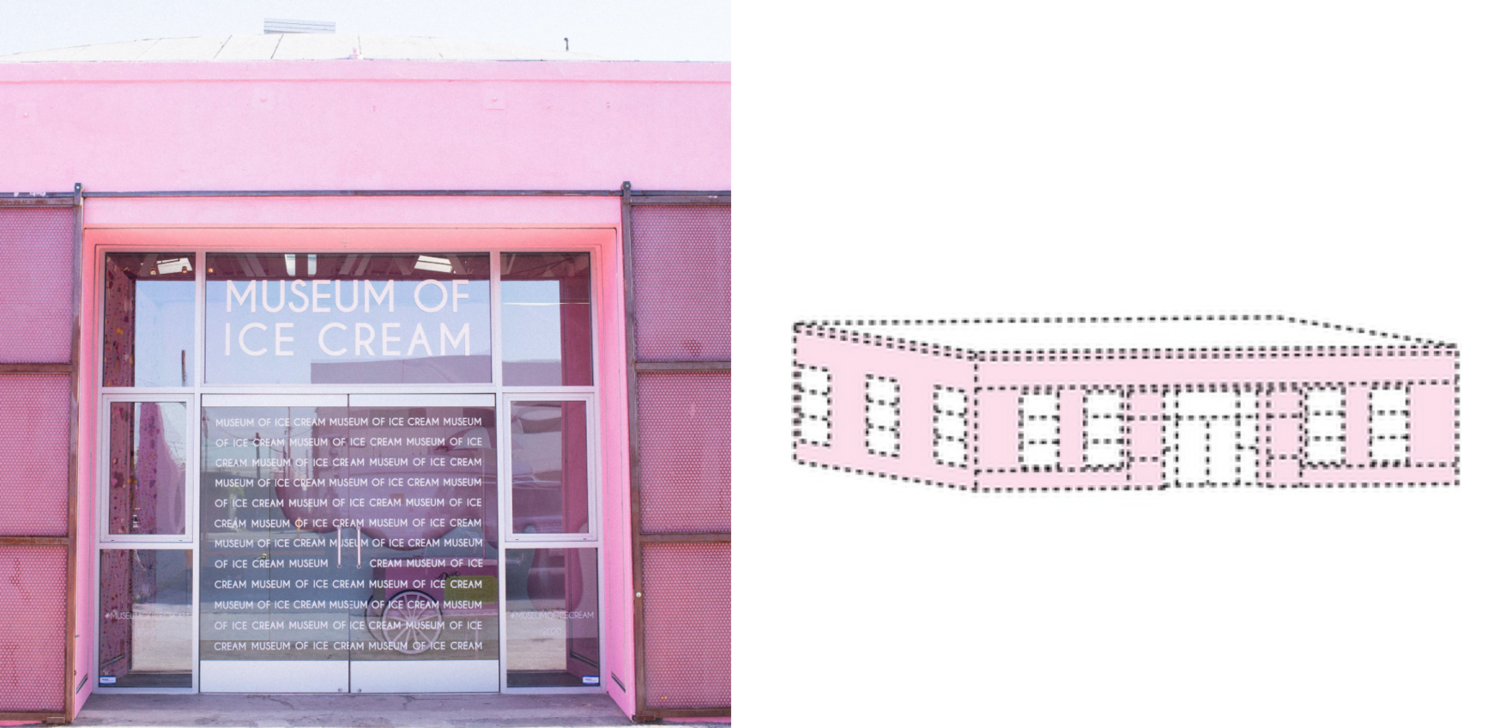

However, the most striking trademark filing comes by way of an application for registration filed in December 2017, in which the Museum’s holding company 1 AND 8 Inc. claims exclusive rights in “the color light pink as applied to a building in connection with entertainment services, namely, physical environments in which users can interact for recreational, leisure or entertainment purposes.”

One of the Museum’s outposts (left) & 1 AND 8 Inc.’s trademark drawing (right)

One of the Museum’s outposts (left) & 1 AND 8 Inc.’s trademark drawing (right)

Can one company claim the exclusive right to operate their business from inside a light pink building? That is the question at issue before the USPTO.

Given how the human mind works, color as a trademark makes sense. Trademark attorney and former USPTO examiner Ed Timberlake told TFL, “It might be fair to say that our understanding of cognition suggests that color is one of the qualities we notice first. With that in mind, it doesn’t seem like a stretch to me to think that quite often color – used consistently and in a trademark manner [i.e., as an identifier of source] – will be capable of indicating source.”

The USPTO agrees. In a non-final decision issued early this year, the trademark body held that it is, in fact, possible for companies to maintain exclusive rights in connection with specific uses of specific colors, citing Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp’s 20-plus year use of the color pink on residential insulation as an example of a color achieving “acquired distinctiveness” and thus, being protectable by trademark law, as one example.

The USPTO further held that while there are not any existing registrations that are too similar to 1 AND 8 Inc.’s application and would, therefore, block its ability to register its mark. However, the USPTO’s decision it is not looking promising for the wildly popular Instagram haven.

According to the Trademark Office, the Museum has not made its case. It stated the well-known trademark tenet that color is never inherently distinctive (meaning that they will never, on their face, serve to identify a source of goods/services, and as a result, making the bar for claiming rights in colors higher than for most traditional trademarks). As such, the USPTO stated that 1 AND 8 Inc. must show that its proposed mark has acquired source-indicating significance in the minds of consumers.

In short: It must show that the average consumer is able to identify a light pink building as being tied to a single company, something that can be demonstrated by showing of advertising expenditures by the company, sales success, length and exclusivity of use, unsolicited media coverage, and consumer studies.

The USPTO found that 1 AND 8 Inc. failed to provide the necessary evidence, noting that “a mere statement of long use [of the color] is not sufficient.” Moreover, the USPTO held that the press clippings that 1 AND 8 Inc provided, which “show the popularity of [the Museum’s] services … are insufficient to show acquired distinctiveness of the applied-for mark because the press clippings do not show that consumers have come to identify the color pink, used on the external surfaces of buildings, as being a source identifier for [the Museum’s] services.” Additionally, the USPTO notes, “very few of the clippings [provided] even mention the color pink.”

1 AND 8 Inc. responded to the USPTO’s decision last month, proposing to cut down on the language in its description for the goods/services covered by the mark to exclude “children’s entertainment and amusement centers, namely, interactive play areas.” It has also sought to alter its registration from being included on the USPTO’s Principal Register – which is reserved for the registration of marks that are distinctive – to the Supplemental Register, which provides protection for non-distinctive marks that may be capable of acquiring distinctiveness.

“It might not be entirely crazy to liken registration on the Supplemental Register to opening a show off-Broadway,” Timberlake says. “People would usually prefer to open on Broadway (the Principal Register), but opening off-Broadway isn’t necessarily the kiss of death.” In other words, 1 AND 8 “requesting registration on the Supplemental Register might not be a bad way to spend their time while they endeavor to amass evidence of source-indication.”

The USPTO has not yet responded to 1 AND 8 Inc.’s latest filing. So, stay tuned …