California is focusing its attention on the rise in sustainable marketing, including recycling-centric claims by way of a new law that mandates when recycling labels – including the “chasing arrows” motif – can be used. According to the bill, which was signed into law earlier this month by California Governor Gavin Newsom, unless a product or packaging is considered recyclable “pursuant to statewide recyclability criteria and is of a material type and form that routinely becomes feedstock used in the production of new products or packaging,” the use of “a chasing arrows symbol, among other symbols, statements [indicating the product is recyclable directly on the product], or directions,” will be deemed deceptive or misleading.

The new law – which amends Sections 17580 and 17580.5 of California’s Business and Professions Code and calls on the state’s Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery to publish standards on or before January 1, 2024 regarding what types of material types/forms are considered recyclable – applies to all consumer goods and product packaging, unless otherwise specified. And it is being widely characterized as the nation’s strictest standard for when items can (and cannot) display the recycling symbol and any other representation that advises consumers that a product or its packaging can be recycled.

The impact of the new recycling marketing law is limited in terms of its applicability – at least directly – to products sold within the state of California. However, it is likely to have a significant effect on brands if for no other reason that the sheer size of the consumer goods market in California. Beyond that, experts expect that the law will likely catch on in a broader capacity. Come 2024, when the law goes into effect, “California’s new stricter standard will likely become the rule to meet when it comes to recyclability,” says Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz attorney Jordyn Eisenpress. And while the Federal Trade Commission’s Green Guides “provide federal-level guidance on environmental marketing, state environmental marketing laws offer a patchwork of restrictions, resulting (similar to/as has been the case with privacy legislation), in the largest most-restrictive states setting the tone for the space overall.”

California’s law is the first of its kind in the U.S., although other states are, in fact, turning their attention to recycling. Maine and Oregon have enacted laws that require corporations to foot the bill for the cost of recycling their packaging, with the legislature in Oregon laying plans to put a taskforce in place to address potentially “misleading or confusing [recycling] claims” related to recycling. At the same time, a bill that relates to “false claims about recyclability and plastic container labelling” is pending in the New York Senate.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom’s Competition & Markets Authority recently published its highly anticipated Green Claims Code, with the competition and consumer protection regulator providing guidance for businesses making environmental claims. The newly-issued Code” – which is aimed at “helping businesses understand and comply with their existing obligations under consumer protection law when making environmental claims” – applies to all businesses across market sectors, and extends to claims made in advertisements, product labelling and packaging or other accompanying information, including product names, and presumably, logos or graphics that are used in connection with companies’ goods/services.

The Rise of “Green,” Recycling TMs

The flurry of activity comes as companies continue to bank on rising consumer sentiment around the need to consume more consciously by way of often-sweeping sustainability campaigns complete with no shortage of eco-buzzwords. Unsurprisingly, the widespread adoption of sustainability-centric marketing messaging by brands across the board – from fast fashion and high fashion names to beauty brands and consumer packaged goods companies – has brought within it a spike in misleading and/or unsubstantiated claims, and a bevy of confused consumers.

It will be interesting to see how far the impending crackdown on recycling – and other “eco-friendly” –symbols and advertising language will eventually go, as companies have been working overtime to cater to consumers’ growing climate concerns. The result goes beyond dedicated marketing campaigns and specific “green” products (such as recycled capsule collections), and also comes in the form of a growing amount of “green” trademark filings across the globe. The European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”), for instance, revealed in a report last month that more than 2 million applications for registration for what it calls “green trademarks” have been filed since 1996, with the volume of marks that make mention of “green terms,” such as recycling, “increasing significantly both in absolute figures and as a proportion of all EU trademark filings.”

“The main finding of the study,” according to the EUIPO is that “environmental considerations are becoming increasingly important for brand owners filing trademark applications, and to the consumers who are buying the resulting products and services.”

Reflecting on the EUIPO’s findings, Pinsent Masons’ legal director Désirée Fields stated, “With climate change and environmental issues featuring heavily on the global agenda in politics, business and public debates, consumers increasingly seek to purchase products which are considered to be environmentally friendly and sustainable, [and] trademarks can play an important part in helping consumers identify that they are purchasing a product that meets these characteristics.”

Aside from “certification marks, collective marks or guarantee marks, which indicate to consumers that a product complies with certain standards or characteristics,” Fields notes that companies have taken to adopting trademarks that not only indicate to consumers that a product or service originates from a particular source, but that they result from “an undertaking which, usually through heavy investment in marketing and education of consumers by the brand owner, have come to be recognized as ‘green brands.’”

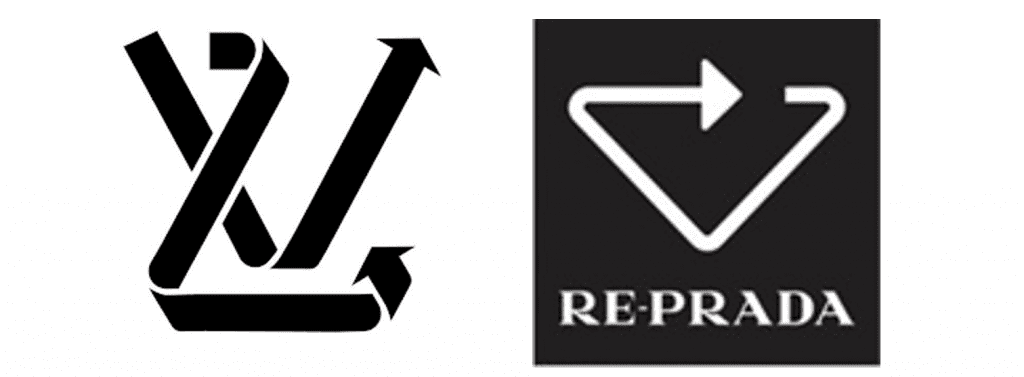

In this vein, marks that suggest elements of sustainability, such as recycling, are on the rise, as well. Prada, for instance, has filed applications this year for a mark that consists of the word Re-Prada along with a stylized take on its triangle logo for use in connection with its push to use recycled nylon – or econyl, a proprietary material made from upcycling industrial nylon waste like fishing nets and carpets – across its accessories offerings. Meanwhile, Louis Vuitton similarly filed an application for registration with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for a mark that consists of two twisting arrows that make out the letters “LV” for use on “upcycled” sneakers.

Marks like these are interesting in that they may not make use of the recycling symbol, itself. They do, however, implicitly make sustainability-centric claims by virtue of their appearance, and thus, may be subject to things like the FTC’s Green Guides, for instance, which apply to “environmental claims in labeling, advertising, promotional materials, and all other forms of marketing in any medium, whether asserted directly or by implication, through words, symbols, logos, depictions, product brand names, or any other means.”

“Investing in and integrating environmental protection and sustainability into a company’s brand [growth and] protection strategy can add value,” Fields says, given that there is “so much focus on these important issues globally.” While that remains true in light of rising regulator crackdowns on misleading sustainability marketing, including “general environmental benefit” claims – and the willingness of consumers and independent watchdogs to call out brands and/or initiate litigation in some cases, brands would be wise to consider the balance the benefits of such branding with the potential ramifications.