From Gucci girls to Dior homme dudes, luxury brands’ ad campaigns tend to have near-uniform subjects: young models hawking “it” bags, buzzy footwear, and/or expensive garments in furtherance of the industry’s unabashed obsession with the youth. It was not all that long ago, after all, that Francois-Henri Pinault, CEO of Kering, the corporate parent to Gucci, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, and Bottega Veneta, among others, revealed that millennials and Gen Z were responsible for nearly 50 percent of Gucci’s total sales. Meanwhile, UBS estimated that the purchasing behavior of consumers between ages 21 and 37 accounted for 33 percent of Louis Vuitton’s revenues.

Taken together, millennials and Generation Z consumers, those born between 1981 and 1996, and 1995 and 2015, respectively, were responsible for 33 percent of all luxury sales worldwide in 2018, according to consulting firm Bain & Co., a number that is expected to jump to as much as percent by 2025. All the while, they drove a whopping 85 percent of the growth in the $1.36 trillion luxury goods market as of 2017. In short: “New generations will be the primary engine of growth for the luxury market in the coming years,” as Bain put it.

With such sizable purchasing power and even more striking growth in mind, it is hardly surprising that luxury brands are pulling out all of the stops to cater to these younger consumers, particularly young-but-high-spending Chinese shoppers. But in its focus on this segment of consumers, fashion brands (and beauty brands, too) are setting themselves to miss out on a powerful consumer class that is right in front of them with money – oftentimes, a lot of money – to spend: aged 50 and above.

According to research from the International Longevity Centre (“ILC”), as cited by the Guardian, the fashion industry’s unwillingness to cater to older consumers could cost it. In a December 2019 report, entitled, “Maximizing the Longevity Dividend,” the London-based think tank found that rampant “institutional ageism” in the fashion and beauty industries stands in direct opposition to concrete figures that show growing spending by consumers that are over age 50. At stake, according to the ILC? Nearly $15 billion over the next 2 decades.

While the fashion industry is focusing on chasing millennial and Gen Z dollars, including by almost always representing only those demographics in their ad messaging and to a large extent, in their product offerings, “older people increased their spending on clothes and shoes by 21 percent – or $3.80 billion – between 2011 and 2018.” In the United Kingdom, alone, the group found that individuals over age 50 accounted for nearly 50 percent of spending as of 2018, up from 41 percent in 2003.

Looking ahead, that number is expected to grow further. By 2040, ILC projects that individuals aged 50 and over will be the fashion sector’s “key consumer base.”

“Not only are today’s over-50 consumers wealthier, they are also healthier and have more time to spend their money before and during retirement,” Ina Mitskavets, senior consumer and lifestyles analyst at Mintel, told the Guardian. “All these factors are contributing to a rise in a mature demographic of shoppers eager to explore all the options available to them.”

Statistics are similar in the U.S., where consumers age 50 and older account for half of all consumer spending, with individuals between ages 55 and 64 outspending the average consumer in nearly every category, including clothing and beauty, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ U.S. Consumer Expenditure Survey. More generally, baby boomers, those born between 1944 and 1964, commanded some 70 percent of the country’s disposable income (as of 2019) and were spending $3.2 trillion a year, according to U.S. News & World Report.

Meanwhile, Havas’s 2018 “Meaningful Brands” study revealed prominent e-commerce growth among consumers ages 55 and over, asserting that nearly 70 percent were making at least one online purchase every month.

Despite the striking statistics for consumers over age 50, who are also generally less burdened by debt than young consumers, this group is being targeted by only a small fraction of large-scale marketing efforts by fashion and beauty brands (and just 10 percent of marketing as a whole, per the AARP), and as the ILC puts it, those industries, in particular, have “been bewilderingly resistant to recognizing just how fashionable and stylish the generation of older consumers are and want to remain.”

Tricia Cusden, the founder of Look Fabulous Forever, a beauty brand aimed at older women, echoes this notion, saying that brands are making a mistake in overlooking those outside of the millennial and Gen-Z brackets. Baby boomers, in particular, she says, “are ageing in a completely different way from our mothers and grandmothers,” and desire to be provided with “style, relevant fashion and service” by brands and retailers.

In the best case scenario for fashion and beauty brands, their overarching aversion to speaking directly to older consumers means they are simply passing up on a lucrative segment of the market. A worse case sees them aliening these consumers entirely, something that the ILC says is, in fact, in play, noting that many “women older than 75 stop spending on fashion altogether, even though they have significant savings and say they are still interested in looking stylish.”

Those that are shopping “are not necessarily spending on clothes,” Maureen Hinton, director of research and analysis at Verdict, the retail consultancy, told the Financial Times a few years ago, “because many retailers are not targeting them successfully.”

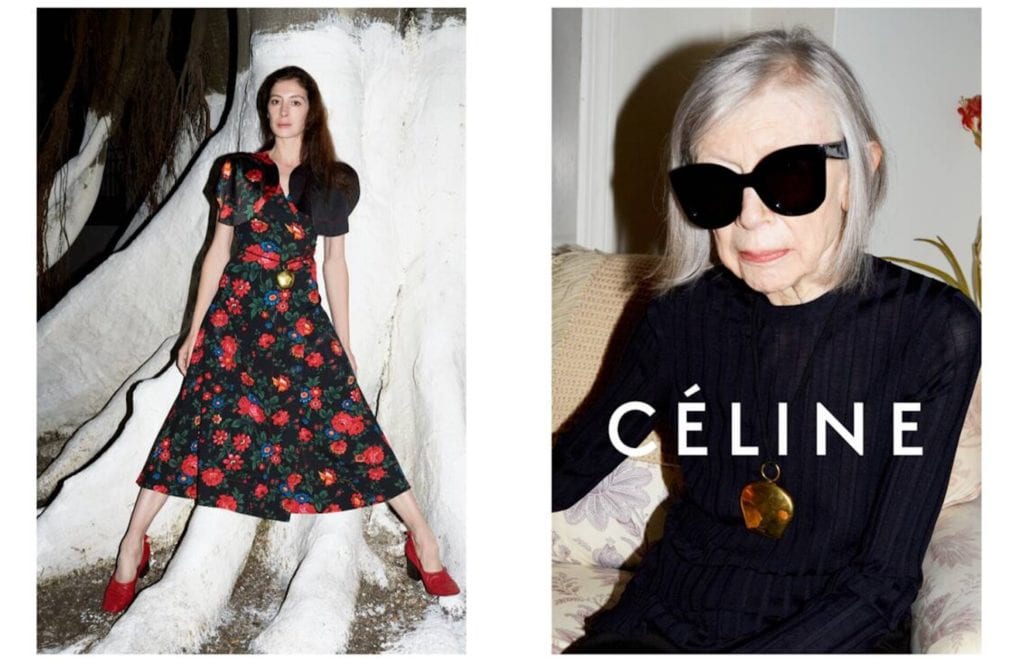

As for whether change is really afoot, there is certainly momentum. “One huge shift that seems to be making a difference is the power of older women on social media and Instagram,” Ari Seth Cohen, the creator of senior-centric blog Advanced Style, told the Guardian. This coincides with a rise in visibility in traditional ad campaigns. The Guardian noted that over the past decade, “older models have been increasingly used in advertising campaigns.” From former Celine creative director Phoebe Philo putting 82-year-old author Joan Didion front and center in a 2015 ad campaign for the Paris-based brand to Jane Fonda and Helen Mirren fronting ads for L’Oréal.

But the influx of more mature models in high fashion marketing (and the runway) “has never become the norm,” the publication notes.

Potentially more important than the attitudes and actions of brands in the upper echelon of the fashion industry are those of more mainstream brands and retailers, where the real bulk of consumer shopping is actually done.

(For a point of comparison, TJX Companies, for instance – which owns T.J. Maxx, and Marshalls, among other discount retail chains – generated revenues of $35.9 billion for 2018, quite a bit more than the $20 billion annual sales figure reported by Gucci, Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, and Balenciaga’s parent company Kering for the year. On the other hand, Costco, alone, sold $7 billion worth of clothing in 2018.)

In this section of the market, brands and retailers say that are trying to do better. A spokesman for Marks and Spencer, for one, stated last year, “We’re changing our core M&S clothing collection to deliver stylish wardrobe staples with broad appeal.” Maybe others will follow.