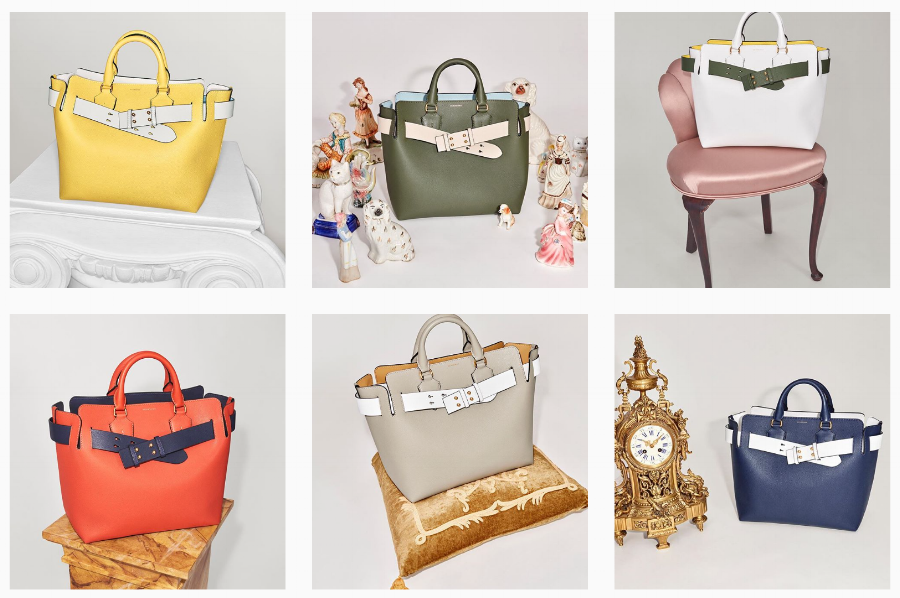

image: Burberry

Burberry is following in the footsteps of its fellow high fashion brands and acquiring one of its key suppliers. The British stalwart brand announced on Monday that it will be taking a team of around 100 leather goods specialists in-house as part of the deal agreed with CF&P, one of its longstanding Italian leather suppliers in a move to “boost its handbag business in a drive to take its brand more upmarket” with the help of former Celine CEO Marco Gobbetti and new creative director Riccardo Tisci, who comes by way of Givenchy.

As Reuters so aptly notes, “Luxury goods firms tend to make the largest chunk of revenues from high-margin leather accessories [as opposed to garments], and many seek where possible to cut out the middle-man, giving them more control over costs and turnaround times.” This is something CEO Gobbetti – who helped transform Celine from a dusty fashion brand to a globally-coveted maker of leather goods – well knows.

Burberry showed an array of surprisingly lust-worthy bags on the runway for Spring/Summer 2018. The power of its checkered canvas bags, and the more upscale leather ones that followed, is not to be underestimated. Unlike many of its biggest competitors, Burberry has, for years now, lacked an “it” bag.

In addition to churning out covetable accessories, Burberry’s rivals have been moving manufacturing and other operations in house in recent years. While Reuters states that Louis Vuitton and Hermes have long maintained manufacturing in-house, Gucci joined the camp in expanding its internal capabilities in opening a 800-person leather goods facility in Tuscany.

Chanel made headlines in 2016 when it purchased four of its silk suppliers in an attempt to further control its precious supply chain. The announcement came on the heels of a number of other supplier acquisitions by the Karl Lagerfeld-helmed house. In June 2016, the Paris-based design house took a majority stake in the family-run Richard Tannery, a provider of lambskins for its small leather goods – its second leather-specific acquisition in recent years. And in case that is not enough, that April, Chanel bought a minority stake in 129-year-old tulle and lace supplier Sophie Hallette near Calais, France’s lace capital.

The practice of luxury brands snapping up suppliers goes far beyond Chanel, and in fact, signifies a much broader industry trend. You may recall that beginning in the mid to late-2000’s luxury brands and conglomerates began buying up their leather suppliers with increasingly frequency in an effort better to control their supply chains.

Rival LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton similarly acquired one of its most integral suppliers several years ago, buying Heng Long, a crocodile tanning company. In October 2011, the French brand offered $160.8 million for a Singapore-based tannery, paying $0.60 each for all 268 million shares of the company. (Key Heng Long shareholders agreed to sell a total of 73.7 percent; Heng Long management has decided to reinvest $69.5 million in a joint venture where LVMH and Heng Long maintain ownership stakes of 51 percent and 49 percent, respectively).

Several years later, Prada entered into a deal to gain a controlling interest in France’s Tannerie Megisserie Hervy, which specializes in lambskin tanning, in particular soft plonge nappa leather. Prada also entered into the venture with Tuscan tannery Conceria Superior, a long-time industrial partner of the Milan-based brand.

And in an epically grander move, Hermès, the Paris-based brand known for its Birkin and Kelly bags, started breeding its own crocodiles eight years ago. In 2009, Hermès resorted to breeding its own crocodiles on farms in Australia to try to meet demand for its leather bags. According to the company’s then-CEO, Patrick Thomas: “It can take three to four crocodiles to make one of our bags. So, we are now breeding our own crocodiles on our own farms, mainly in Australia.”

The growing trend toward vertical integration – control from the raw material to the shop shelf – which once gave luxury brands a competitive advantage is becoming something of an industry norm.

Ownership of the supply chain not only raises barriers to entry and helps these brands to defend and preserve the high-quality image they want associated with their products, it is simply how business it done at this end of the spectrum.

Most immediately, it ensures that they will be far less likely to experience a shortage of materials for their pricey accessories (and silk for Chanel’s jackets and scarves, of course), for which so many of their businesses are so thoroughly dependent.