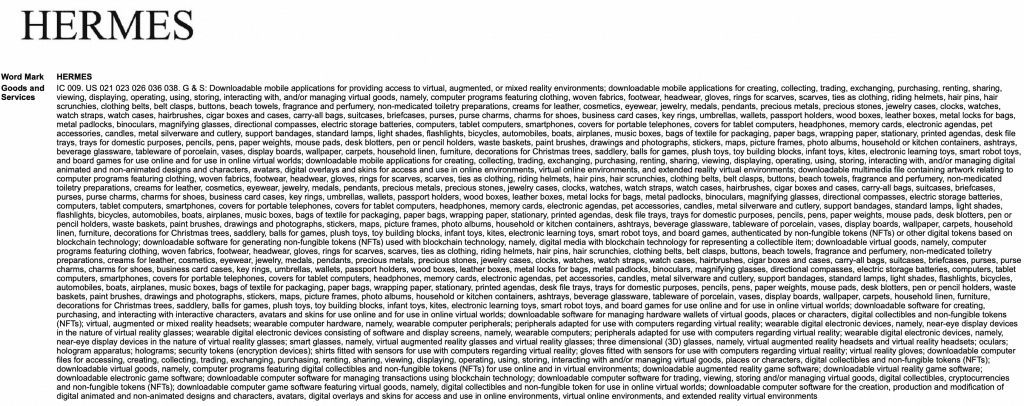

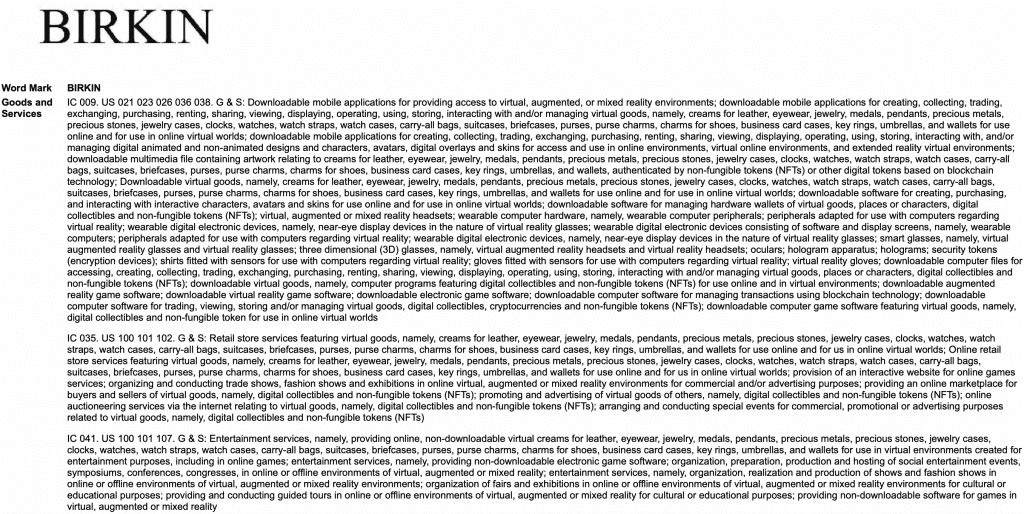

Hermès made headlines last month in the wake of filing a trio of intent-to-use trademark applications, seeking to register its name, along with the Birkin and Kelly word marks, across a number of quintessential metaverse classes of goods/services – namely, Classes 9, 35, and 41 for the two famed handbag style names and a longer list (Classes 9, 35, 36, 41, and 42) for the Hermès word mark. The filings that counsel for Hermès lodged with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office come as the French luxury goods company is embroiled in a trademark lawsuit against Mason Rothschild, which it lodged early this year over his sale of a collection of 100 “MetaBirkins” non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) tied to images depicting furry renderings of its famous Birkin bag.

At the same time, the Hermès applications fall neatly in line with an overarching trend among brands – mass-market entities and luxury goods purveyors, alike – that have filed similar applications for registration with the USPTO and other trademark offices, often in an effort to hedge their bets when it comes to the budding rise of the metaverse and new technologies like NFTs. How can we tell that brands are hedging by way of these applications? Look no further than the disparate classes they are filing for, which illustrate, among other things, that they are not quite sure what they are going to do in the metaverse – if anything at all.

By intentionally casting a wide net, listing goods/services that range from metaverse-centric entertainment services to technologies for crypto payments, companies are both following the lead – and the language – of early-moving parties (such as Nike) and looking to cover their bases for their future endeavors in this realm, even if they do not know exactly what those endeavors will look like.

It is difficult (for me) to imagine Hermès rolling out a metaverse venture – such as a partnership with platforms like Roblox or Mythical Games’s Blankos Block Party as Burberry and Gucci have done – any time soon. (The company has not even fully embraced e-commerce, announcing just two years ago that it was “going to gradually increase our offer of products online.”) And despite many media reports to the contrary, the applications that the Birkin bag-maker filed, on their own, do not necessarily mean that it has concrete plans to make inroads into the virtual world. Nonetheless, a discussion about some of the takeaways from the Hermès applications is still worthwhile, particularly as at least a couple of points stand out.

Authentication Over the Metaverse

Primarily, it is worth noting that in its application for its name, Hermès includes Class 42, specifically pointing to “authentication, issuance and validation of digital certificates; user authentication services using technology for e-commerce transactions; [and] providing user authentication services using blockchain-based software technology for cryptocurrency transactions,” as among the services it might use its name on. While it is interesting that Hermès (and other companies, such as Dior, Bulgari, Versace, Saint Laurent, Canada Goose, etc.) goes beyond that most commonly-cited metaverse/NFT classes (9, 35, and 41) in its application, it is not necessarily surprising, as it would be far less of a stretch (I think) to see Hermès and other similarly-situated ultra-luxury brands make use of web3 technology more as a way to provide customers with information about their purchases, including on the authentication front, than as part of a metaverse/gaming-centric scenario.

“The most obvious use case of tokenization,” according to fashion and luxury-focused NFT platform Arianee, comes in the form of digital product passports or digital twins that are tied to “real-world assets,” such as luxury handbags or watches, and that can provide “proof of ownership and authenticity by way of an NFT-centric watermarking system.” The benefits here go further, as such digital twins “follow the [corresponding physical] products throughout their lifespan,” and can capture/store information along the way, including in the event that the physical goods are resold and/or repaired or otherwise modified.

The use of NFTs in this way makes sense for luxury brands – especially craftsmanship-focused ones that maintain closely-controlled distribution systems and offer up investment-grade offerings – for a number of reasons. For one thing, no shortage of these brands are placing increased weight on repairs as a way to deepening their connection with clients (and potentially, justifying repeated price increases). Management for LVMH, for instance, recently rejected the idea of participating in the resale market and instead, “emphasized efforts to offer repair services for its products.” At the same time, Chanel – which has famously snubbed the secondary market – has filed trademark applications for registration of the past couple of years that shed light on its increasing efforts on the repair front.

Beyond that, accurate and up-to-date repair records are important, as TFL has reported in the past, in light of the strict stance that many ultra-luxury brands take in terms of the impact that modifications of their goods can have on the authenticity of those products. (As Chanel, for instance, states in connection with its repair/restoration services, “Only the House of CHANEL can offer the appropriate care ritual respecting the authenticity of each creation.” Meanwhile, luxury watchmakers largely treat previously authentic watches that have been modified to include unauthorized parts as inauthentic, which has led to a stream of lawsuits filed by watchmakers and secondary market watch buyers, alike.)

In theory, careful and consistent tracking of modifications could help to alleviate some concerns that brands/consumers have about the authenticity of altered goods, and thus, help to avoid litigation and/or more accurately determine the value of products from a secondary market perspective.

And still yet, this information is useful from a warranty perspective, as certain alterations/modifications serve to void warranties (such as for Rolex), while certain conditions of sale are relevant for warranty purposes. Chanel, for example, offers a five-year warranty exclusively for handbags and wallets on chain that have been acquired from its boutiques beginning in April 2021.

Token-Gated Benefits

The second thing that stands out in Hermès’ filing is the following language – “Creating an online community for registered users to participate in discussions, form virtual communities, and engage in social networking in the field of digital assets” – which also comes by way of Class 42. Is Hermès likely to launch a social media platform for its clients to network? Probably not. However, this seems like it could be a nod to the ability of brands like Hermès to use web3 tech to “reinvent their customer relationship management practices,” according to Arianee, with NFTs, for instance, capable of functioning as digital membership cards that provide consumers with access to “exclusive communities, events, sales, drops, or time-based privileges.”

Such a token-gated approach (by which brands can provide exclusive offers/benefits to token holders) could be especially relevant for companies like Hermès to use in connection with their most coveted offerings. After all, in theory, if an individual has acquired a Birkin or Kelly from an Hermès boutique, it generally means that they have purchased no small number of other Hermès offerings and thus, are the very type of client that the brand would be interested in consistently engaging with. (As distinct from the longstanding narrative about the near-impossibility of “bagging a Birkin,” consumers can get their hands on Hermes’ most prized handbags if they spend enough on the brand’s other offerings (i.e., homewares, ready-to-wear, etc.) and build up a relationship with the brand in the process.)

It is still early days for brands in the web3 arena, making it too early to say with certainty what – exactly – companies (including digitially-hesistant luxury players) will and will not opt to try. Chances are, while companies like Hermès might not jump at the opportunity to create a virtual pop-up in Roblox (save for maybe for things like their beauty ventures), the ultimate outcome for luxury brands in the virtual world will probably consist of a combination of creative products (even if those are merely digital representations of physical goods tied to NFTs that are provided to customers of those physical goods or NFTs tied to product-related editorial content) and uses born from a utility perspective, hence, the reference to authentication services in applications filed by Hermès.

UPDATED (Sept. 15, 2022): In an interview with the WSJ, Hermès CEO Axel Dumas shed light on the company’s thoughts on the metaverse/NFTs, saying: “Blockchain technology allows you to track your supply chain and add data in a faithful way, which is interesting. NFTs as a product for sale in their own right is a trickier question. We are craftsmen, and we’re not just selling an image. But in 10 years if our clients require NFTs to accompany physical products, so they can have an avatar dressed as they are, we can think about it. I’m not sure we’d ever sell an NFT without a physical product, but in a way it won’t be up to us to decide. It will be the client.”