USAPE LLC (“BAPE”) is looking to sidestep the trademark infringement and dilution claims that Nike lodged against it early this year, arguing that the Swoosh has failed to identify its purported trade dress with the necessary level of particularity and thus, the court should toss out the headline-making case in its entirety. In the motion to dismiss that it filed with a New York federal court on May 17, BAPE asserts that not only did Nike wait “nearly fifteen years [from when] it first contacted BAPE” over the footwear/streetwear company’s allegedly infringing footwear, it “has not identified which attributes of its sneakers are distinctive enough to constitute source-indicative, protectable trade dress, making it impossible for BAPE or any other shoemaker to know what designs to avoid in order to steer clear of Nike’s alleged rights.”

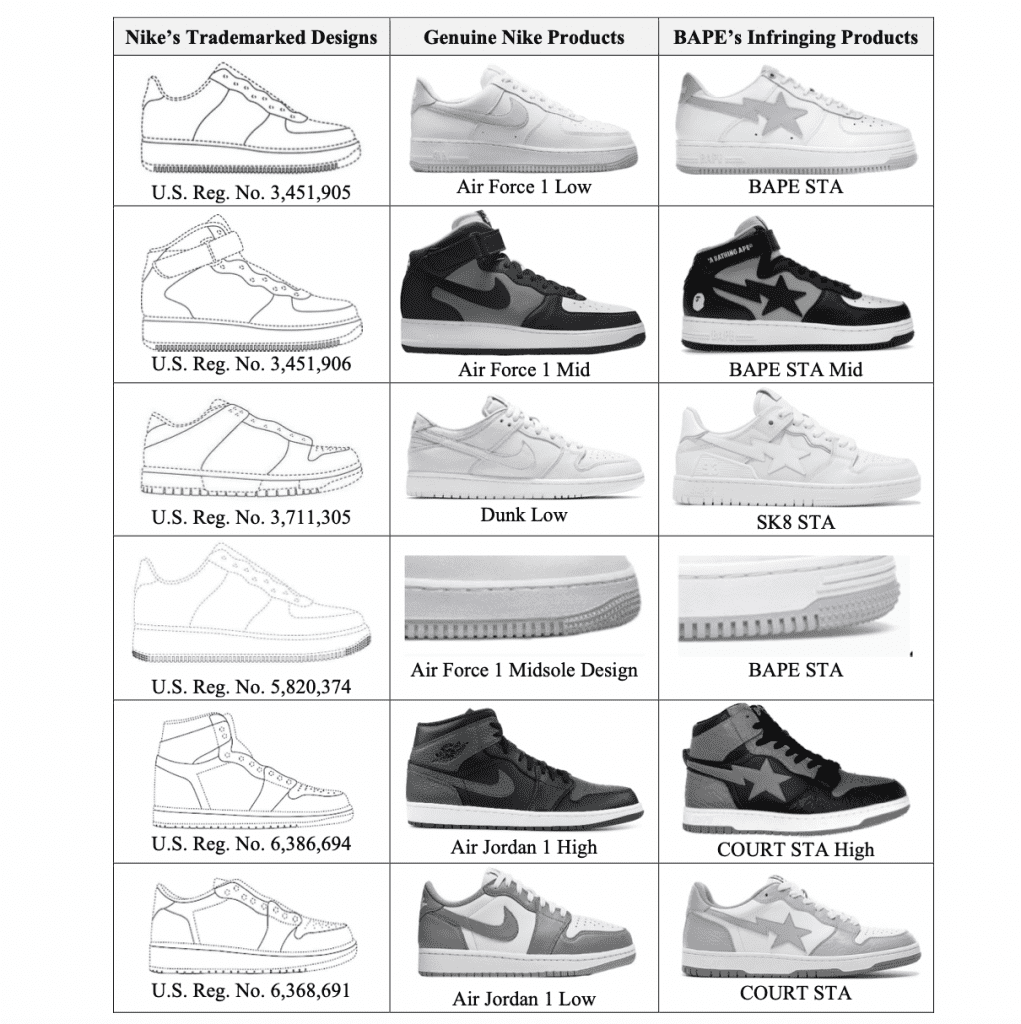

For some background: Nike filed suit against BAPE in January, alleging that while BAPE first introduced infringing footwear in the U.S. in 2005, for the majority of that time, BAPE’s infringement was “de minimis and inconsistent,” and thus, did not warrant litigation. It was not until 2021 that the company began to escalate its infringement scheme, prompting Nike to wage trademark claims on the basis that BAPE sneakers infringe its Air Force 1, Air Jordan 1, and Dunk sneaker designs.

Mirroring the claims it made in a letter to the court in February, BAPE asserts in its motion to dismissal that despite Nike’s numerous trademark claims, the sportswear giant “has failed to identify the elements of its purported trade dress” with the requisite specificity to pursue a claim for trade dress infringement. Citing previous SDNY case law, BAPE claims that this includes “an articulation of which of the plaintiff’s trade design elements are distinctive and how they are distinctive,” and it notes that “the standard for pleading trade dress protection is particularly high for product configuration trade dress … because [p]roduct design is driven primarily by the usefulness or aesthetic appeal of the object.”

Instead of pleading “any of the elements that make up its trade dress” in the Air Force 1, Air Jordan 1, and Dunk sneakers, BAPE maintains that Nike merely “provides the registration numbers associated with the asserted marks, the drawings attached to the asserted trademark registrations, and photographs containing images of certain shoes allegedly bearing the [infringed] trade dress,” per BAPE. “These pleadings are not sufficient to describe Nike’s trade dress with specificity,” it argues. According to BAPE, this is made worse by the fact that Nike is suing over “several iterations of its trade dress,” which makes it “even more important to identify the individual elements.”

BAPE goes on to respond to the arguments that Nike made in its defense in a joint letter to the court last month. (In the joint letter, Nike argued that it sufficiently pled the elements of its trade dresses by including with its complaint “detailed written description[s] and corresponding diagrammed illustration[s]” from its trademark registrations. Pointing to the relevant registrations, Nike argues that “courts in this district and others have found that referencing and incorporating federal trademark registration certificates is sufficient to identify the asserted trade dress with particularity.” Nike specifically cited Nat’l Hockey League v. Hockey Cup LLC, in which the court held that the NHL’s “list[ing of] its registrations for its Stanley Cup trade dress in the complaint” satisfied the trade dress pleading requirement.)

BAPE counters Nike’s argument here, citing the SDNY’s decision in Rémy Martin & Co. v. Sire Spirits LLC, in which the court held that “[a] plaintiff cannot simply submit an image and expect the court to determine what part or parts constitute protectable trade dress.” Nike’s inclusion of its trademark registrations is not enough, according to BAPE, as the descriptions of marks from the asserted registrations are “impermissibly vague,” as they “identify parts of a shoe but do not describe which elements of those parts are supposedly source indicative or what is distinctive about each of those elements.”

“Because Nike has failed to allege any elements of its asserted marks, let alone a description of how those elements are distinctive,” BAPE argues that the court should dismiss the complaint.

Finally, BAPE asserts that this is not the first time it has pushed Nike to elaborate on its trade dress rights. Back in 2009, in response to contact from Nike over its allegedly infringing sneakers, BAPE asserts that “despite [its] request that [Nike] do so, Nike refused to explain the source and nature of its alleged rights and dropped the matter.” Nike contacted BAPE again in 2012, per BAPE, “but again, Nike quickly dropped the matter.”

The case is Nike, Inc. v. USAPE LLC, 1:23-cv-00660 (SDNY).