A new filing in a trademark case that pits Nike against BAPE sheds light on Nike’s alleged pattern of granting “naked licenses” to third party sneaker-sellers in order to sidestep their efforts to invalidate the trademark registrations that it has amassed for some of its most famous sneaker designs. In an answer and corresponding counterclaim that it lodged with a New York federal court on March 18, BAPE is angling to escape the trademark infringement, dilution, and false designation of origin/unfair competition case waged against it by Nike early last year by getting the court to cancel a number of Nike’s registrations for its Air Force 1, Jordan 1, and Dunk trade dress, which serve as the basis for Nike’s closely-watched case.

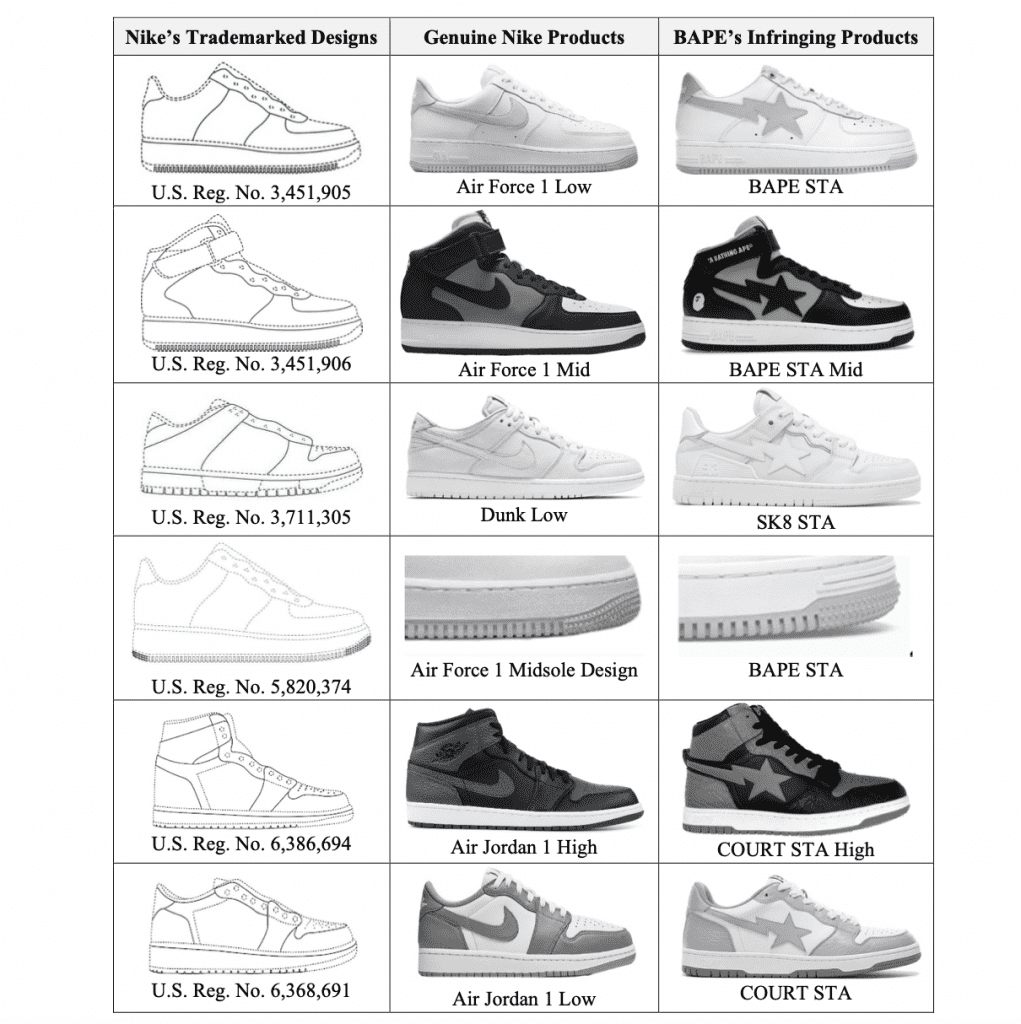

For some background: Filing suit against BAPE in January 2023, Nike alleged that the Japan-based sneaker and streetwear company has been engaged in an escalating infringement scheme by way of its manufacture and sale of sneakers that co-opt the registered trade dress for its the Air Force 1, Air Jordan 1, and Dunk sneaker designs. While BAPE sought an early dismissal of the case in May 2023, urging the court to toss out Nike’s claims on the basis that it waited too long to take legal action and has not sufficiently alleged the elements of its trade dress, Judge Paul Gardephe of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York refused to rule on whether Nike has met its burden of establishing its trade dress and thus, kept the case firmly in place.

Nike’s “Naked Licenses”

In the wake of the court denying its motion to dismiss, BAPE appears to have shifted its focus to some extent to draw the court’s attention to Nike’s alleged failure to police certain uses of its Air Force 1, Air Jordan 1, and Dunk trade dress. By failing to consistently take action to control the use of its trade dress in the aforementioned styles, BAPE claims that the sportswear titan has effectively forsaken its rights in those sneaker configurations, and the court should invalidate Nike’s U.S. registrations as a result.

“By granting third parties ‘naked licenses’ (i.e. permission to use Nike’s purported trade dress without maintaining any control over the quality of the sneakers bearing that trade dress), Nike has abandoned any rights it may have developed in that trade dress,” BAPE argues.

Delving into the naked licenses allegedly granted by Nike, BAPE claims that the Swoosh has granted “at least one sneaker company” – Already LLC – and any licensee of Already’s “immunity” from future trademark actions in connection with the lawsuit that Nike filed against Already back in 2009. In that case, Nike alleged that two of Already’s sneaker styles violated its Air Force 1 trademark. Already responded to Nike’s trademark claims by challenging the validity of its Air Force 1 trade dress registration, which ultimately prompted Nike to issue a covenant not to sue in order to “save its feeble registration from cancellation,” per BAPE.

At the same time, BAPE maintains that the covenant not to sue also permitted the private labelling of sneakers featuring its Air Force 1 trade dress. In other words, Nike allegedly went so far as to “allow other sneaker brands,” namely, Already and its licensees, “to place their word marks and logos on sneakers bearing Nike’s purported trade dress” – albeit without also including Nike’s own word marks or logos, thereby, “eliminat[ing] any connection consumers may have had between the purported trade dress on one hand, and Nike as the source of sneakers bearing that trade dress on the other.”

By doing this, BAPE contends that Nike “severed the connection in the minds of consumers between [the] purported Air Force 1 trade dress and Nike as a source” of that trade dress since “consumers would be confronted with sneakers bearing Nike’s purported trade dress, without the Nike word marks or Logo, [and] instead bearing the word marks and logos of others.” (Note: In furtherance of the covenant not to sue, Nike to refrain from bringing “any trademark or unfair competition claims against Already or any of Already’s past or future licensees … based on the Air Force 1 trade dress,” and then sought to get the case dismissed, including Already’s invalidation counterclaim, arguing that there was no longer a case or controversy at play.)

That case – and the covenant not to sue and corresponding naked licensing – is relevant here, according to BAPE, as while Nike still maintains three registrations for its Air Force 1 trade dress (Reg. Nos. 3,451,905, 3,451,906, and 5,820,374), the covenant not to sue serves to invalidate Nike’s rights in that trade dress “by granting third-parties permission to use its purported trade dress on sneakers without retaining any control over the quality of those sneakers.” And that is just one example, per BAPE, which claims that Nike has “permitted widespread third-party use of its purported Air Force 1, Air Jordan 1, and Dunk trade dress, beyond the use of the Air Force 1 trade dress by Already,” thereby, warranting the invalidation of a handful of Nike’s trademark registrations.

With the foregoing in mind, BAPE requests that the court dismiss Nike’s claims against it with prejudice and seeks an order from the court that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office cancel each of the relevant Air Force 1, Air Jordan 1, and Dunk trade dress registrations.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: The Supreme Court’s decision in Already v. Nike in 2013 – in which the majority held that Nike’s covenant mooted Already’s cancellation counterclaim – confirmed that companies like Nike can successfully use covenants not to sue as contractual shields to escape trademark invalidation counterclaims. Not necessarily a ramification-less win for Nike, though, the case raised questions about what impact of the covenant not to sue might have on Nike down the road and in particular, what it might mean for Nike’s ability to enforce its Air Force 1 trade dress against alleged infringers that are not party to the covenant.

Now, more than 10 years after the close of Nike’s case against Already, the notion that a broad covenant not to sue could negatively impact a company’s ability to enforce its rights in a mark is being put to the test.

The case is Nike, Inc. v. USAPE LLC, 1:23-cv-00660 (SDNY).