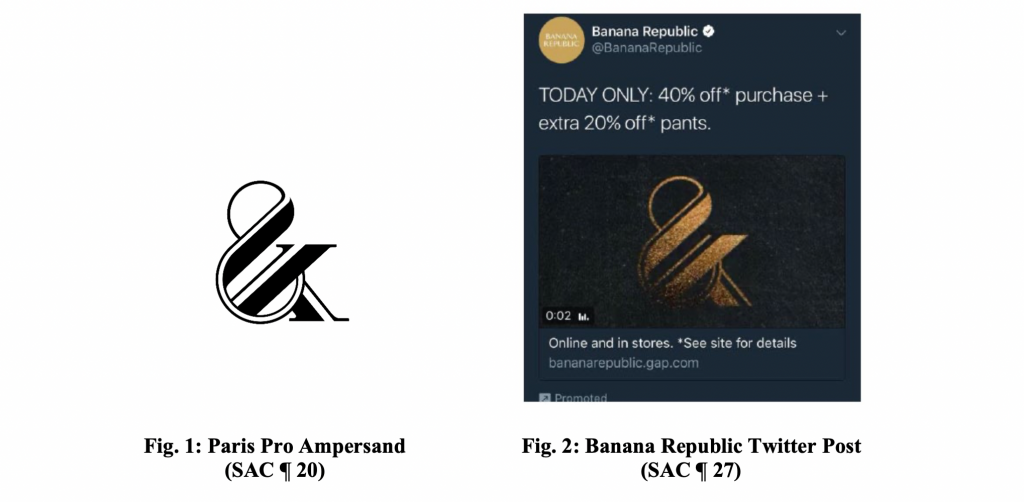

Banana Republic has managed to escape an unjust enrichment claim waged against it by Moshik Nadav Typography LLC, which claimed that the retailer co-opted the graphic design firm’s stylized ampersand symbol for a campaign of its own, thereby “depriv[ing] Nadav of any compensation for the commercial use of [its] work, while presenting Nadav’s work as its own.” Judge Jesse Furman of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York tossed out the unjust enrichment claim once and for all, while granting the design firm the opportunity to amend its insufficient unfair competition and New York General Business Law (“GBL”) claims.

In a memorandum and order dated June 10, as first reported by Law360, Judge Furman held that Nadav had failed to make its unjust enrichment claim primarily because it failed to allege that any relationship existed between itself and Banana Republic. “Unjust enrichment is available only in unusual situations when circumstances create an equitable obligation running from the defendant to the plaintiff,” according to Judge Furman, who states that in lieu of establishing any relationship between itself and Banana Republic, Nadav claimed that a relationship could be assumed based on its allegation that “Banana Republic misappropriated the Paris Pro Ampersand directly from Nadav.”

The court was not convinced by Nadav’s claim, and held that “the fact that Nadav has designed typefaces and logotypes for other entities in Banana Republic’s industry falls short of plausibly suggesting that the two companies had any relationship, dealings, or communications.” Moreover, even if Banana Republic were aware of Nadav, or of the fact that the New York-based firm had designed the Paris Pro Ampersand, “an unjust enrichment claim cannot be predicated on a defendant’s mere knowledge of the plaintiff’s actions.” If that were sufficient, “then the requirement would be rendered meaningless,” the Judge stated, dismissing Nadav’s unjust enrichment claim.

Judge Furman then turned his attention to Nadav’s unfair competition and GBL s. 349 claims, both of which he dismissed – albeit while giving Nadav the opportunity to amend the two deficient claims.

First up, the court determined that Nadav’s unfair competition claim must be dismissed because it failed to plausibly show that Banana Republic acted in bad faith, as required for under New York law, according to precedent from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. “Although Nadav pleads that Banana Republic acted in ‘bad faith’ by ‘deliberate[ly] and/or intentional[ly] copying . . . the Paris Pro Ampersand, it fails to support that conclusory assertion with any specific factual allegations,” the court stated. Beyond that, Judge Furman held that Nadav did not show that Banana Republic was even aware of “the existence of Nadav, the Paris Pro Ampersand, or the fact that Nadav had designed the Paris Pro Ampersand,” and without such awareness, “Banana Republic plainly could not have intentionally copied the design.”

Again, the court held that relying on the sheer similarity between the Paris Pro Ampersand and the ampersand that Banana Republic used in order to “suggest that Banana Republic must have intentionally copied [Nadav’s] design” is not enough. “Visual similarity alone is generally insufficient to support an inference of bad faith,” the judge held, and since Nadav did not provide any further support, the court dismissed the unfair competition claim.

Finally, in terms of Nadav’s GBL s. 349 claim, which prohibits deceptive and misleading business practices, the court sided with Banana Republic on the basis that Nadav did not allege that “any consumer suffered a cognizable injury as a result of Banana Republic’s alleged misappropriation of the Paris Pro Ampersand.” At the heart of the case is “a dispute between Nadav and Banana Republic over Banana Republic’s allegedly unauthorized use of a close approximation of the Paris Pro Ampersand in its marketing and social media campaigns,” the court notes. As such, the “core of the claim is a dispute between businesses, not harm to consumers,” and with that in mind, the court dismissed the claim, granting Nadav leave to amend to address the deficiencies in the GBL and its unfair competition claims.

The case – which Judge Furman says “might have dubbed the Case of the Stolen Ampersand” by Encyclopedia Brown – got its start back in October 2020 when Nadav filed suit, alleging that Banana Republic “engaged in an extraordinary, large-scale and widespread commercial use” of the little “and” symbol from its “distinctive and unique” Paris Pro typeface in an “extensive digital marketing” campaign, as well as on its “worldwide social media platforms.”

Not your average ampersand, Nadav – which describes itself as an “innovative typography and graphic design business” with clients that have included Vogue, Estee Lauder, Elle UK, Ann Taylor, Volkswagen, Harrods, Target, and GQ – has argued that the symbol is a “unique artistic logogram” that serves as “the centerpiece of Nadav’s brand identity.”

The case is Moshik Nadav Typography LLC v. Banana Republic, LLC, 1:20-cv-08325 (SDNY).