Trademark rights in (and registrations for) a single letter for use on certain goods/services? This is not only possible under trademark law in the U.S., but as it turns out, it is pretty common, as well. “Single letters are among the most popular trademarks registered in the United States,” Chris Chafin previously wrote for Fast Co. Back in 2017, each letter of the alphabet was the subject of, at a minimum, hundreds of trademark registrations, he noted. There were, for example, over 2,000 registrations for the letter S, making it the most popular. There were 1,102 registrations for V, 1,100 for E, and 1,816 for A. And those numbers have risen since then, there are currently almost 1,000 registrations for the letter X, as companies flock to and secure trademark registrations for single letters, usually in stylized forms.

The background here is this: While trademark laws in “many countries” make it so that “marks such as single letters or numerals are considered nondistinctive,” Baker & Hostetler’s Robert B.G. Horowitz stated not too long ago that this is not the case in the U.S., “which has a very broad definition of what comprises a trademark.” In accordance with the Lanham Act, trademarks can consist of “any word, name, symbol, or design, or any combination thereof, used in commerce to identify and distinguish the goods of one manufacturer or seller from those of another and to indicate the source of the goods.” And this includes single letters.

A Case(s) Note: Single letter trademarks have been at the center of an array of cases and proceedings before the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) over the years, including: (1) Singer Mfg. Co. v. Singer Upholstering Sewing Co., in which a W.D. Pa. court found, in part, that the letter “S” is a valid trademark for use on sewing machines and related products; (2) Michelin Tire Corp. v. General Tire Rubber Co., a TTAB proceeding that centered on Michelin’s X mark; (3) Quality Semiconductors, Inc. v. QLogic Corp, in which an N.D. Cal. judge held that a stylized letter “Q” mark was conceptually strong because it was “arbitrary” and “unique” within the industry; and (4) New Balance Athletics, Inc. v. New Bunren Int’l Co., in which a federal court in Delaware determined that New Balance’s “N” marks are both conceptually commercially strong.

Meanwhile, in Professional Sound Services, Inc. v. Guzzi, an SDNY judge held that the plaintiff’s use of a letter “S” without “any unique design or stylized appearance” was not inherently distinctive, and that the plaintiff failed to provide any evidence to show that “the naked letter ‘S’” was “capable of distinguishing its goods from goods of others.” And for an international view, L’Oréal nabbed a favorable outcome before the European Union’s General Court last year in a case that centered on two trademarks that consisted (mainly) of the single letter “K” letter.

Cubs v. Create

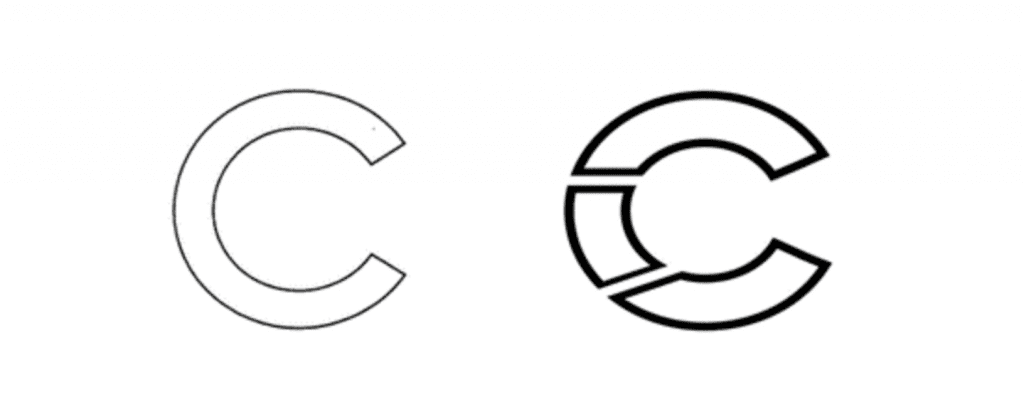

Horowitz points to an opposition proceeding that Chicago Cubs Baseball Club, LLC lodged against The CREATE Inc. in 2018 as a good example of “how a mark comprising a single letter is protectable and enforceable.” In that case, CREATE Inc. filed a trademark application for registration for a stylized letter “C” for use on “Hats; Headbands; Hoodies; Jackets; Shirts; Sweaters; Sweatpants.” In response, the Chicago-based baseball team sought to block the application on the basis that it has rights in and registrations for “C” marks of its own for use on “clothing, namely, caps, hats, headwear, headbands, shirts, t-shirts, baseball uniforms, jerseys, sweatshirts, sleepwear, jackets,” etc.

Before sustaining the Cubs’ opposition, the TTAB considered a number of the likelihood-of-confusion factors from In re E I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., and held that the goods on which the two parties were using their respective “C” marks were “identical or overlapping,” such goods would travel in the same channels of trade and be offered up to the same classes of consumers, and the marks, themselves, were highly similar in appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression.

One DuPont factor worth looking at here is, of course, the strength of the opposer’s mark, as it sheds light on the robustness of the Cubs’ “C” mark and potentially, single letter marks more broadly. The TTAB held that it had “no evidence that the letter ‘C’ has a particular significance in the clothing industry” and it similarly lacked evidence of “third-party registrations of marks comprised solely of the letter ‘C’ for the same or similar goods that might demonstrate the inherent weakness of this component as a source identifier.” As a result, on this record, the Board held that the Cubs’ registered mark for the identified goods is “inherently and conceptually strong.”

At the same time, the TTAB considered the number and nature of similar marks in use on similar goods, a factor that explores whether “customers have become so conditioned by a plethora of such similar marks that customers have been educated to distinguish between such marks on the bases of minute distinctions.” On this front, the TTAB held that it had “no evidence that consumers have been exposed to so many letter C trademarks for use in connection with apparel that [they] ‘have been educated to distinguish between [such] different marks on the bases of minute distinctions.’”

Such an analysis is interesting for a few reasons, not least of which is the fact that it is a clear indication that while parties can amass trademark rights in and registrations for single letter trademarks, such rights are likely to be narrow in most cases, particularly where the marks commonly used in connection with the goods/services at issue. New Balance’s various “N” marks come to mind here, as the relevant trademark registrations convey relatively narrow protections. Instead of providing the sneaker-maker with unencumbered rights in the letter “N” for use on footwear, the registrations are limited by stylization-centric specifics, such as “a stylized representation of the letter ‘N’ with a contrasting border,” or “a stylized representation of the letter ‘N’ that is slanted and has curved edges at the top and bottom.”

Twitter’s new X logo also comes to mind due to the notable number of entities that maintain trademark registrations for X in the tech space (and beyond), including Facebook-owner Meta and Microsoft. This will inevitably serve to limit rights that the Elon Musk-owned company amasses in the mark to the specific design of the logo and thus, limit its ability to claim infringement in connection with marks that are not confusingly similar to the logo design, itself, and not merely uses of the letter X on similar gods/services.

Against this background (and considering the policy considerations that weight against providing companies with a monopoly on single letters), companies are likely to have the most luck from a protection – and certainly an enforcement – perspective when their marks go beyond the single letter to stylized depictions of it. And the same will hold true from an enforcement perspective, as well.

A QUESTION TO GO: The very-finite-scope of the rights at play and the potentially very limited opportunities for enforcement for single letter trademarks ultimately raise the question of what the value of such marks is. From a branding standpoint, single letter trademarks offer up benefits, particularly given the space constraints of things like iPhone icons and social media profile photos. (Adopting single letter marks could be the newest iteration of the larger branding trend that saw companies pare back their logos in order to implement them more seamlessly across multiple formats.) The inherently short nature of single letter marks also may make them visually appealing and capable of being incorporated into a larger stylized word mark or logo, the latter of which stands to help companies to bring consistency and continuity to their branding.

For Twitter, experts are less-than-bullish on brand value in the wake of the company’s recent adoption of single letter branding; although much of the skepticism seems to have less to do with the new single-letter-logo than it does with the overarching shift away from a well-known brand. “Musk’s move wiped out anywhere between $4 billion and $20 billion in value,” Bloomberg reported, citing analysts and brand agencies, including Steve Susi, director of brand communication at Siegel & Gale, who says, “It took 15-plus years to earn that much equity worldwide, so losing Twitter as a brand name is a significant financial hit.” Allen Adamson, co-founder of marketing and brand consulting group Metaforce, took a similar view, telling Fortune the rebrand is “completely irrational from a business and brand point of view.”

As for the enforceability of single letter marks, such as those in the X realm, we might not have to wait long to see if/how such a case is waged. In light of the large number of companies that maintain registrations for X marks and if the lawsuits that followed Facebook’s rebrand to Meta are any indication, Musk’s venture will almost certainly land on the receiving end of a trademark suit very soon.