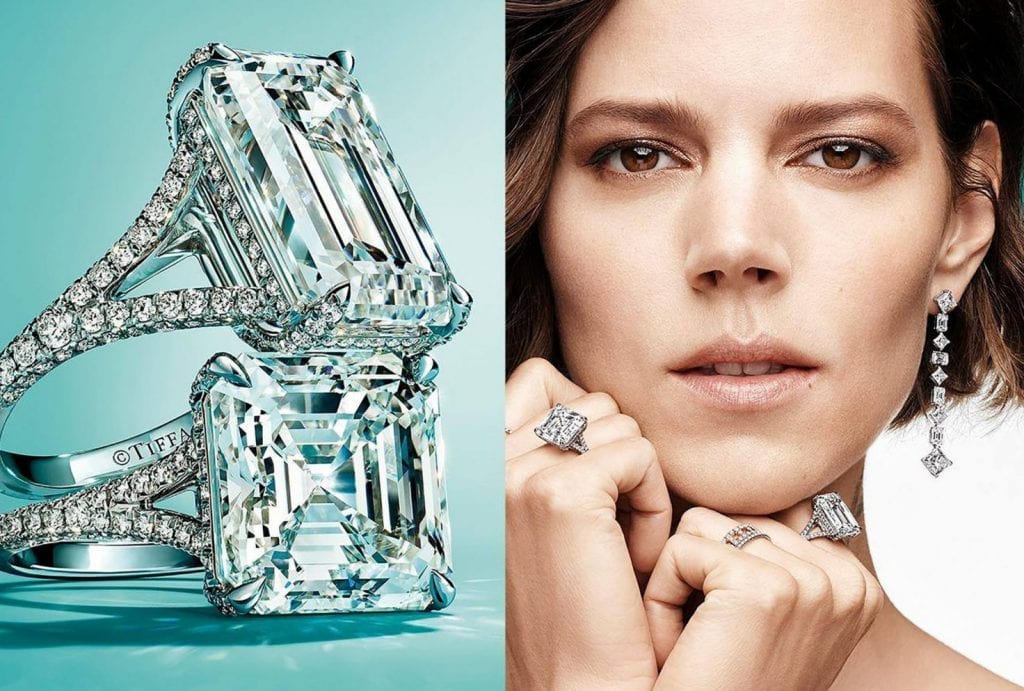

Tiffany & Co. “beat Wall Street expectations for quarterly profit as the U.S. jeweler benefited from an over 70 percent rise in sales in China and a recovery in demand at home,” Reuters reported on Tuesday. “We had a strong third quarter, which speaks volumes about the enduring strength of the Tiffany brand and gives us confidence as we enter the important holiday season,” Chief Executive Officer Alessandro Bogliolo said in connection with the company’s quarterly revenue report for the three months ending October 31, 2020.

The results do “bode well for the upcoming holiday season for the jeweler and other luxury retailers in general, which have been hit hard by the pandemic,” per Reuters, and a 30 percent rise in revenue in the Asia-Pacific region “underscores the growing importance of sales within mainland China to offset [their] dependence on tourism, especially on Chinese tourists visiting fashion hubs like Milan and Paris.”

Beyond that, though, the sizable uptick in sales is particularly interesting given that just two months ago, LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton sought to pull out of its $16 billion-plus deal to acquire Tiffany & Co., pointing to the way in which the stalwart jewelry company’s “management and its Board of Directors … has handl[ed] the [COVID] crisis,” and arguing that Tiffany’s business was thoroughly “devastated” by the global health pandemic.

LVMH’s attempt to back out of the $16.2 billion deal swiftly prompted Tiffany to file suit, with the New York-headquartered jeweler seeking an order from a Delaware Chancery Court judge requiring LVMH to “abide by its contractual obligation under the merger agreement to complete the transaction on the agreed terms.” LVMH responded by threatening litigation of its own on the grounds that its board “had the opportunity to examine the current economic situation of Tiffany and its management of the crisis,” and found that “the first half results and its perspectives for 2020 are very disappointing, and significantly inferior to those of comparable LVMH Group [brands] during this period.”

The Bernard Arnault-run conglomerate further asserted that Tiffany had failed to “follow an ordinary course of business, notably in distributing substantial dividends when the company was loss making,” while also claiming that “the operation and organization of [Tiffany] are not substantially intact,” thereby, invoking the Material Adverse Effect (“MAE”) clause in the parties’ merger agreement, which they signed-off on in November 2019, ahead of the onset of COVID.

In the complaint that it did eventually file, LVMH argued, among other things, that Tiffany “hemorrhaged cash for the first time in a quarter century, with no end to its problems in sight,” and asserted that “Tiffany’s performance will continue to be poor,” at least in part because its “retail strategy” is “particularly ill-suited for the challenges ahead” and will “have a significant long-term detrimental impact on the company.” With that in mind, and given “the decision by two sophisticated parties, represented by sophisticated advisers, to omit a pandemic carve,” LVMH stated the pandemic has, in fact, “caused a material adverse effect that allows LVMH to terminate.”

What MAE?

From the outset, Tiffany characterized LVMH’s MAE allegations as lacking in “factual, contractual or legal support,” and argued that “nothing alleged by LVMH has come close to meeting the MAE definition in the merger agreement, which excludes all ‘changes or conditions generally affecting the industries in which [Tiffany] operate[s]’ and ‘general economic or political conditions.’”

Now that the dust has settled on the Tiffany v. LVMH legal battle, the current state of Tiffany’s business – which saw it beat Wall Street expectations with a “smaller-than-expected decline” in revenue of 1 percent to $1.01 billion for Q3, as opposed to expectations of a lesser $980.71 million in sales – seems to back up its assertions that LVMH’s sweeping MAE claims were largely without merit. To be exact, Tiffany’s recently-reported results call into question the veracity of LVMH’s previous assertions that the “pandemic has devastated Tiffany’s business,” that “[its] recent woes are just the beginning of its troubles,’” and that the company was being mismanaged in light of the COVID pandemic, thereby, creating a contractual “out” for LVMH.

In other words, Tiffany’s “strong trading improvements” and “beat on the profit line” in Q3 (as Bernstein analyst Luca Solca put it) goes against LVMH’s previous deal-breaking argument that Tiffany was in the midst of suffering from a “durationally significant downturn,” or MAE, according to Brian JM Quinn, a professor at Boston College Law School, who focuses on corporate law, M&A, and transaction structuring.

Clues in the New Deal

But even before Tiffany topped analysts’ expectations for the quarter, there were some marked indications – namely in the terms of the deal that resulted from the parties’ renegotiations after Tiffany filed suit – that Tiffany’s business may not have been faring quite as poorly as LVMH had publicly proffered, and thus, that LVMH’s likelihood of success on the MAE front was very slim.

The “new” deal that Tiffany and LVMH were ultimately able to reach in late October, one that shaved a single-digit percent off of the total purchase price by dropping the price that LVMH will pay for each Tiffany share from $135 to $131.50, seems to evidence that Tiffany was not in quite as much trouble as LVMH may have made it seem. While LVMH did get a 2 percent “discount” in accordance with the terms of the amended merger, bringing the total price tag of the deal to $15.8 billion, that price drop was not a purely one-sided gain for the luxury goods titan.

A close read suggests that the renegotiated price was not necessarily the result of MAE-esque financial turmoil on the part of Tiffany that made it an outlier compared to other industry players in the wake of COVID. In reality, it was a trade off, with Tiffany getting “real value” in exchange for that 2 percent, according to Quinn. “The deal that Tiffany got for giving up 2 percent basically included no walkaway rights for LVMH.” Tiffany’s executives “basically said, ‘Sure, we will give you 2 percent off, but if we have to go back to the Chancery Court to try to enforce this deal, the price that will be used by the court for determining damages is not $131.50 but $135, the original price.”

Put another way, if the deal does not get done, Tiffany will, nonetheless, “get full price” for it.

An underreported term that was added to the amended merger agreement, sets this out, stating that “in the event that [Tiffany] brings any claim, litigation, or other similar proceeding to enforce the terms of the amended merger agreement or for money damages, the ‘Per Share Merger Consideration’ will be deemed, for all purposes in such proceeding, including any award of specific performance or damages, to be $135.00 in cash … as was in the original merger agreement.”

Beyond that, Tiffany also benefits from the removal of two conditions that were previously included in the original merger agreement: one that conditions the closing of the deal on “the absence of a law or order in effect that enjoins, prevents or otherwise prohibits the consummation of the merger issued by a governmental entity,” such as if the French government sends LVMH a letter formally requesting that it delay the deal, and another that mandates that the deal cannot close if there is a material adverse effect in play.

As the amended merger states, these “conditions to the consummation of the merger” are removed, thereby, giving LVMH far less room to potentially wriggle out of the deal.

These new terms are hardly unimportant, according to Quinn, who says that they take away “all the conditionality” and give Tiffany “a lot of certainty” in connection with the newly-fashioned deal, which is valuable in dealmaking, especially given the history between the parties to this transaction. At the same time, the language of the amended merger gives Tiffany “the ability to jam Arnault if [he] tries to go back” on the deal for a second time.

They Almost Never Work

In terms of the reliance on MAE clauses generally, which have been thrown around quite a bit in conjunction with the onset and enduring duration of COVID, from the Tiffany, LVMH deal to assertions made when Sycamore sought to get out of its deal to acquire Victoria’s Secret’s parent company L Brands early this year, the potential for success is extraordinarily unlikely. In short: they almost never work.

To date, there has only been one instance in which a court has found that an MAE has occurred, and thereby, allowed a buyer to terminate an existing deal to acquire another company. In that case, Akorn, Inc. v. Fresenius Kabi AG case, the Delaware Chancery Court determined in 2018 that an MAE existed and that the buyer had validly terminated a merger agreement on the basis that the MAE at issue “substantially threaten[ed]” the earnings potential of the entire business of the target “in a durationally significant manner.”

That is, however, almost certainly not what would have transpired in connection with LVMH’s MAE claims. In a situation like COVID, which “doesn’t impact Tiffany, per se,” Quinn says, but “impacts the entire world” – including other luxury retailers – “in the same way,” an MAE claim would not have proven a fruitful defense for LVMH. This is likely why the luxury goods group agreed to settle the matter – and make peace with Tiffany – after asserting MAE claims in a countersuit of its own.

As for the deal that LVMH ultimately got, it is not exactly the glowing victory of renegotiation that it has been made out to be. Put simply, LVMH did not really get a “deal” or a “discount,” according to Quinn, noting the not-insignificant strings attached to the mere 2 percent price drop, or $425 million savings off the original $16.2 billion price tag.

“It is basically the equivalent of going into a Tiffany store and asking for a 2 percent discount on a diamond,” he says. “You’re embarrassing yourself just by asking for it.”