Sales on a Chinese e-commerce platform called Dewu are exploding thanks to its offering of heavily discounted luxury goods, including coveted bags, footwear, and jewelry, among other goods from the likes of Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Prada, Gucci, and Hermès. The almost 10-year-old marketplace – which offers up “brand-new, authenticated goods” acquired outside of China and resold for discounts of up to 40 percent their original retail price – is swiftly gaining traction on the mainland, as consumers seek discounts amid an enduring economic downturn.

Dewu works like this: Sellers on the increasingly popular platform procure luxury items from companies’ stores and/or e-commerce sites in countries outside of China and transport them back to the mainland, where they offer them at an often-heavily-discounted rate. Thanks to “hefty luxury taxes” and a frequent “disconnect” between prices in China and other markets (which is due, in part, to a lack of global price harmonization), Bloomberg recently reported that the practice is “profitable for parallel importers even after shipping costs and discounts.”

Daigou Grows Up

Once a cottage industry of individuals that catered to Chinese consumers angling to avoid added taxes and growing price tags on luxury goods, the gray market – or daigou – is growing up. Nowadays, it “should be thought of less as an army of individuals,” as the practice has spawned “big organizations that are able to make money through razor-thin margins at scale,” Thomas Piachaud, head of strategy at China-focused consultancy Re-Hub, previously stated.

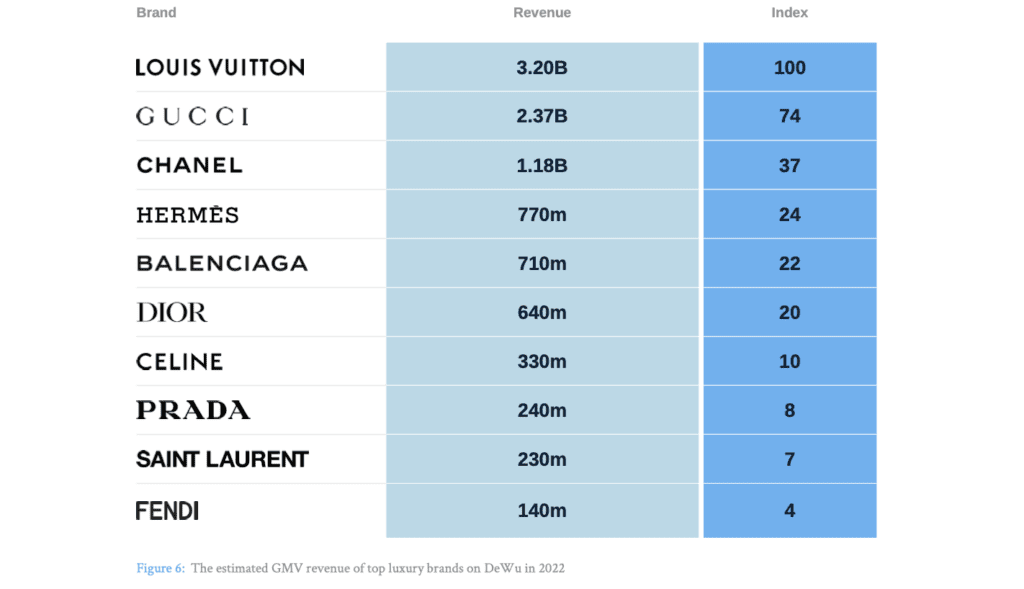

With the growing strength and sophistication of the Chinese gray market has come an eye-watering increase in sales. Dewu, alone, accounted for 73 percent of China’s gray market revenue for 10 top luxury brands across key categories as of August last year, a report from Re-Hub reveals. More broadly, Dewu and other companies like it are contributing to an evolving system of parallel trade in China, where the gray market as a whole generates an estimated $81 billion in revenue each year, with the luxury sector playing a key role, per Re-Hub.

Meanwhile, a March 2024 report from Bain & Co. projected that gray market sales could represent “as much as 70 percent of some companies’ official turnover in mainland China.”

The luxury goods sold on sites like Dewu are originally purchased from the manufacturing brands in countries outside of China, thereby, generating revenues for the brands. But these parallel imports are not without drawbacks: They “erode companies’ profit margins,” impact companies’ operational efficiencies and supply, and “lay waste to the billions of dollars that fashion houses have invested in building up stores and operations in China,” per Bloomberg. They also stand to tarnish companies’ meticulously-curated public profile. During LVMH’s FY2022 earnings call last year, LVMH chairman and CEO Bernard Arnault, for example, spoke to the unauthorized sale of gray market goods, saying, “For your [brand] image, there is nothing worse. It’s dreadful.” LVMH CFO Jean-Jacques Guiony echoed this sentiment, noting that parallel imports negatively affect “brand capital.”

These effects – paired with the well-established demand for gray market goods, particularly among younger consumers who have grown accustomed to purchasing from daigou and very well may continue to do so – raise questions about what brands can do about this ever-growing channel of trade.

Down with Daigou

Against that background, there are ways that companies can contend with the rise of the daigou market. No shortage of luxury brands have expanded their online and physical retail presence in order to cater to Chinese consumers directly, which could serve to diminish some of the draw of daigou sellers. At the same time, many luxury entities have significantly reined in their wholesale operations in order to bring most – if not all – of their distribution in-house. (While not a daigou-focused effort, the shift from wholesale to pure retail stands to have a diminishing effect on secondary market sales, nonetheless, since cutting out department stores and other third-party platforms gives brands more control over how their goods are distributed.)

Other brands, such as Chanel and Cartier, for example, have implemented global pricing, a system by which companies harmonize price tags for their goods in order to avoid the price significant gaps in different markets that result from currency fluctuations, taxes/duties, etc. and that fuel price arbitrage. And still yet, brands have introduced quotas on coveted items as a way to quell bulk buying that often funnels directly into the secondary market.

The Legal Angle

Finally, a number of companies have looked to legal avenues in response to the rise in gray market activity targeting their brands. Fendi, for one, filed a closely-watched lawsuit in China back in 2016 against the owner of an unaffiliated retailer, alleging that the use of Fendi trademarks in connection with its sale of gray market Fendi goods – including on its official WeChat account – amounted to trademark infringement and unfair competition.

Siding with Fendi in a decision in March 2021, the Shanghai High Court upheld an appeals court’s decision that Defendant Yi Lang’s infringed the LVMH-owned brand’s trademarks, as its use of the Fendi marks was likely to mislead consumers into believing that it was affiliated with or otherwise endorsed by Fendi, and therefore, was not engaging in fair use of those marks.

The court also found that Yi Lang engaged in unfair competition on the basis that the Fendi name maintains a certain level of market awareness in China, and is well-known among the relevant public, and as a result, is protected as a “tradename” under the national Anti-Unfair Competition Law. With that in mind, the court took issue with Yi Lang’s use of the Fendi trademarks on things like its store signage, shopping bags, and sales receipts, holding that such use was likely to further cause confusion among consumers.

As TFL reported at the time, the decision was a welcome one for trademark holders, as it served to clarify issues in the realm of gray market goods. Daigou and the corresponding sale of authentic but unauthorized goods has been a particularly hotly-debated phenomenon in China (and beyond) in light of the longstanding conflict between parallel importers and trademark owners in China due, in fact, to China’s substantial adoption of the principle of the trademark exhaustion (also known as the first sale doctrine), which generally makes the sale of gray market goods a legitimate endeavor from a trademark point of view.

The outcome in the Fendi case and others like it could provide further ammunition for brands that are looking to crack down on daigou in China, particularly if sellers make extensive – and potentially confusing – use of their marks in connection with the sale of gray market goods.

Updated

September 30, 2024

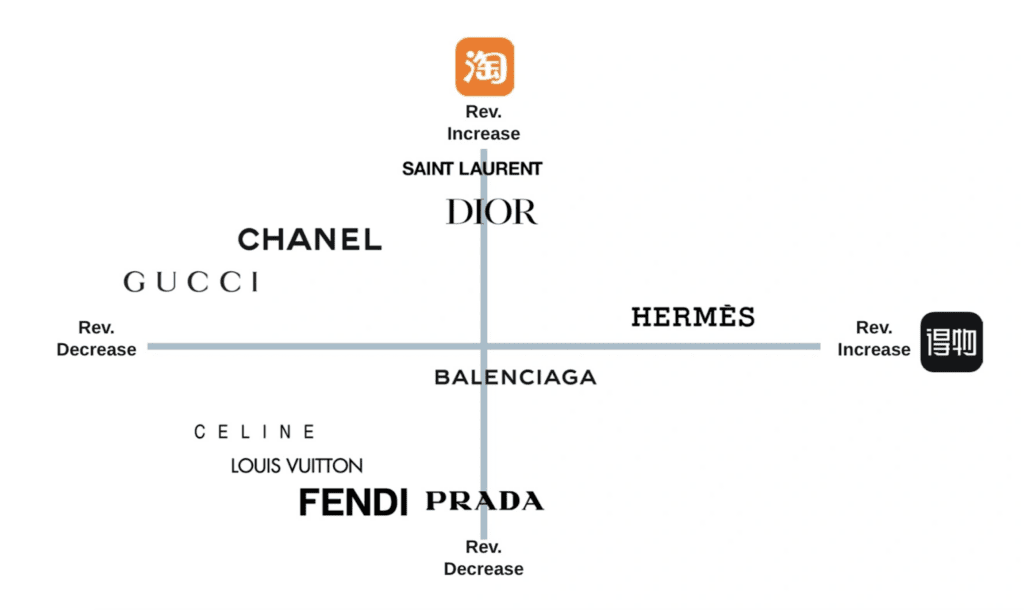

This article was initially published on Aug. 6, 2024, and has been updated to include channel growth/decline in gray market revenue in August 2023 vs. July 2024.