The beginning of a new year is often the impetus for change. For companies, this may mean a rebranding initiative involving an update to a company’s branding, including its logo. In recent years, several major companies – from including Google and Facebook to Starbucks and MasterCard (and even Yves Saint Laurent) – have redesigned their well-known logos in an attempt to appeal to modern consumers.

Although rebranding can provide a boost to a company’s image as a whole, particularly as it evolves in its tangible offerings and/or its larger mission or position in the market, such an exercise is not without potential risks – both in terms of legal rights/protections at play but also in terms of consumer reception. On the legal front, one key concern when it comes to updating a logo or a trademark is the potential loss of trademark rights in a prior logo. This is particularly relevant if that previously-held logo was used for an extended duration, and was recognized and beloved by consumers. At issue in such a scenario will be the need to establish trademark rights and consumer recognition from scratch in a new logo, which will take time and resources, and will also require ensuring that the new logo does not infringe any other parties’ already-existing marks.

Companies that wish to refresh their branding but benefit from the goodwill surrounding a prior mark should consider modifications that update – but do not completely change – the commercial impression of the brand. Under this scenario, a brand owner may be able to rely on the doctrine of “tacking” in a later procurement or infringement matter, which allows a trademark user to “clothe a new mark with the priority position of an older mark,” as discussed by the U.S. Supreme Court in Hana Financial, Inc. v. Hana Bank. (In that case, the court asserted that the test for “tacking” is whether the two marks create the same, continuing commercial impression so that consumers consider both as the same mark).

The doctrine sounds simple in theory; it requires only that the old and new marks be “legal equivalents.” Applying it, however, is more challenging because the determination of legal equivalency depends on whether the two marks “create the same, continuing commercial impression such that the consumer would consider them both the same mark,” as the Federal Circuit stated in In re Dial-A-Mattress Operating Corp.

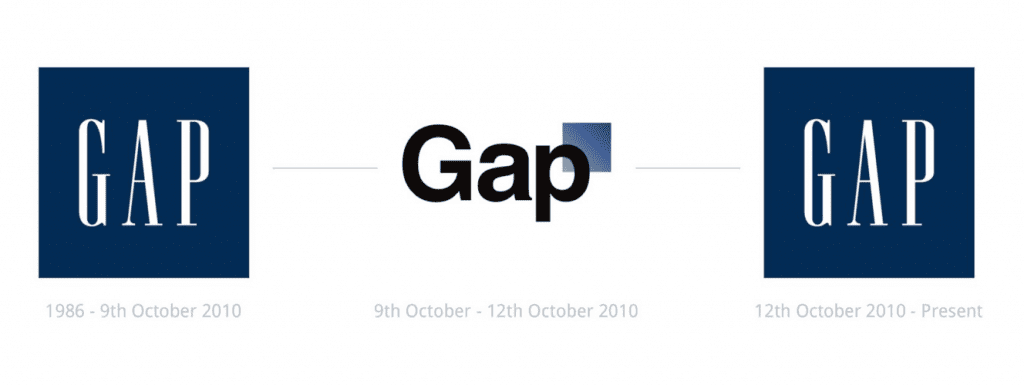

While there are few (if any) hard-and-fast rules, there are a few things to keep in mind when companies are thinking about making changes to their branding. For instance, companies are encouraged to conduct pre-launch market research to ensure that the new mark is well-received by their customers. If done properly, this well enable brands to avoid rebranding fiascos, such as the one that the Gap faced in 2010 when it unveiled a new logo, its first redesign in nearly 25 years.

Consumer response to the rebrand was swift and striking: they hated it, and “Gapgate” was born. Faced with extensive negative feedback from the consuming public, the Gap was prompted to make what media outlets called “an embarrassing U-turn,” scrapping the new logo – a white square encasing a small blue square sitting over the letter “p” in “Gap” – and reverting back to its trusty graphic, the one that consists of the word “Gap” in capital letters inside a dark blue square.

Reflecting on the failed brand at the time, Marka Hansen, president of the Gap brand in North America, conceded that the “outpouring of comments” showed the company “did not go about this in the right way.”

“We missed the opportunity to engage with the online community” when fashioning the revamp, he said, further asserting in response to sweeping consumer complaints, “We’ve been listening to and watching all of the comments this past week. We heard them say over and over again they are passionate about our blue box logo, and they want it back. So we’ve made the decision to do just that – we will bring it back across all channels.”

The failed rebrand reportedly cost the company a whopping $100 million.

With such an instance in mind, companies should consider conducting surveys or other marketplace research to determine whether consumers will appreciate the new mark as a mere extension of the old mark. If they do decide that the rebrand is in their interest, they should then plan an education/public relations campaign that will educate consumers on how the old mark fluidly transitions to the new, to reinforce the continuity of the brand. Finally, they would also be smart to consider and implement a strategy for amending current trademark registrations, or for filing new applications claiming the first use dates of the prior marks, to preserve priority dates for enforcement purposes.

Ivy Estoesta is an associate in the Mechanical and Design practice group at Sterne Kessler. Monica Talley is a Director in Sterne Kessler‘s Trademark practice. (Edits/additions courtesy of TFL)