Amazon garnered attention this summer when it teamed up with Valentino S.p.A. to file suit over the sale of counterfeit goods on its marketplace site. In a 36-page complaint lodged with a federal court in Washington in June, Seattle-based Amazon and fellow plaintiff Valentino alleged that Kaitlyn Pan Group, LLC and Hao Pan were offering up stud-accented footwear that blatantly copied “the iconic look and design of Valentino Garavani Rockstud shoes” on Amazon and a separate site of their own, while making use of Valentino’s “Rockstud” word mark, thereby, “infringing Valentino’s trademark rights and design patents.”

The case got its start on the heels of Valentino determining that Kaitlyn Pan Group and Hao Pan were “knowingly and willfully” manufacturing and selling counterfeit footwear, including on Amazon, and sending a cease and desist letter to them. The famed fashion brand asserted in the jointly-filed complaint that it also alerted Amazon, which similarly put the defendants on “notice” in connection with their sale of the allegedly infringing shoes on Amazon’s marketplace, where Valentino does not stock its products, and ultimately, shut down their seller account as a result of its “rights under [its third-party seller agreement] to protect its customers, Valentino, and the integrity of its store.”

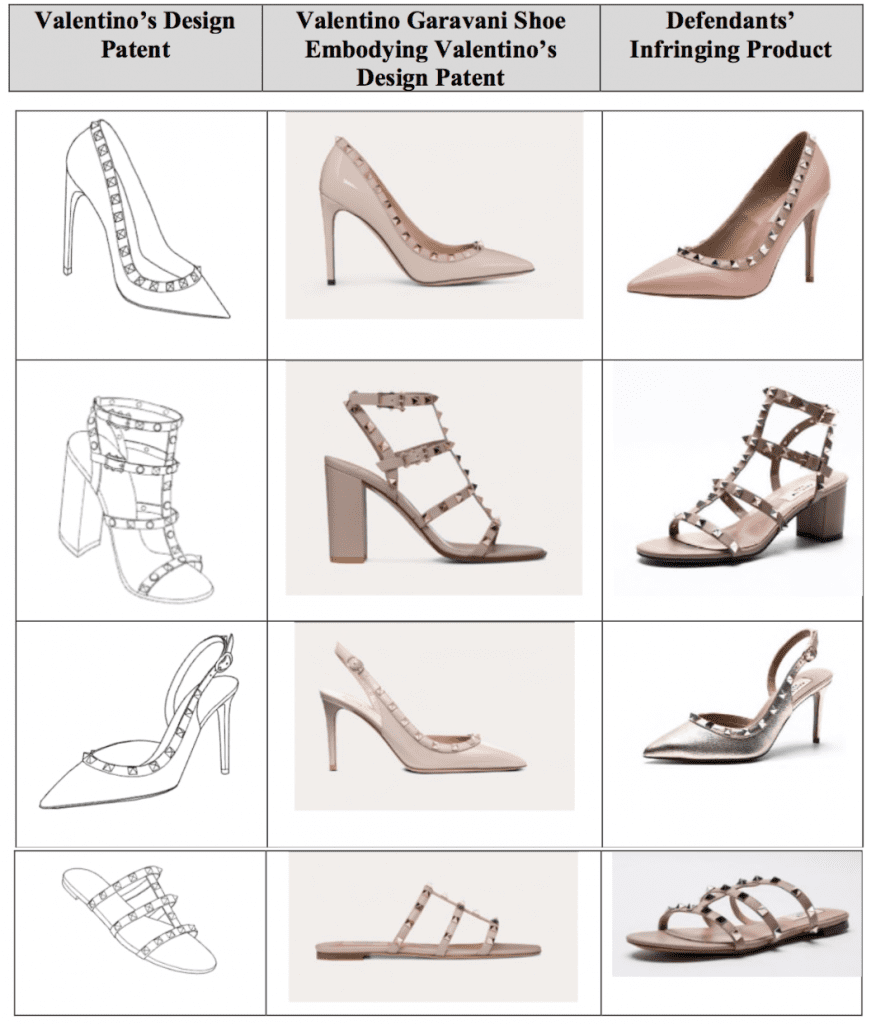

In addition to breaching “numerous provisions” in Amazon’s third-party seller agreement – which “strictly prohibits” the sale of counterfeits (i.e., a “spurious mark [that] is identical with, or substantially indistinguishable from, a registered trademark” that is used on the same types of goods as the ones for which the original mark is registered) and which entitles Amazon “to injunctive relief to stop the defendants from infringing and misusing Valentino’s intellectual property,” Amazon and Valentino asserted that the defendants also ran afoul of federal trademark law. By using the “Rockstud” trademark on lookalike footwear, the defendants created a likelihood that consumers would be confused as to the source of – and/or Valentino’s connection with – the copycat footwear, while also infringing four of Valentino’s design patents that protect the ornamental elements of its various Rockstud shoes.

Finally, Amazon and Valentino asserted that in furtherance of a larger “bad faith” attempt to bank on Valentino’s trademark rights and reputation, Kaitlyn Pan Group and Hao Pan went so far as to file a trademark application for registration with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) on September 10, 2019 for “ROCK’N STUDS BY KAITLYN PAN,” for use on “footwear; shoes; boots; handbags.” The application – which “fully incorporates Valentino’s [Rockstud] trademark,” the fashion brand argued – was filed “after the defendants received notice from Valentino of their infringing activities.” (The application was ultimately declared “abandoned” by the UPSPTO in July 2020 after Kaitlyn Pan failed to respond to an Office Action from the trademark body).

With the foregoing in mind, Amazon and Valentino filed suit and set forth claims of trademark infringement, counterfeiting, patent infringement, unfair competition, and breach of contract, with the latter referring to the defendants’ failure to abide by Amazon’s third-party seller agreement.

Fast forward to December 30, and before Kaitlyn Pan Group and Hao Pan filed their first substantive response to the complaint, counsel for Amazon and Valentino alerted the court that the parties’ had settled their suit. In a notice of settlement and unopposed motion to vacate case schedule, counsel for the two plaintiffs told the court that they have “reached a settlement with Defendants Kaitlyn Pan Group, LLC and Hao Pan,” and are “circulating final settlement documents for execution, but have agreed to all material terms,” none of which have been made public.

Interestingly, the settlement comes just week after Valentino landed a Rockstud-related trademark win, with the USPTO granting three registrations for variations of the hot-selling footwear.

Amazon’s Other Suits

While the Valentino case is readying for a close, Amazon is still in the midst of a number of similar suits. For instance, just two months after initiating the Valentino case, Amazon partnered with another brand, KF Beauty, to file a joint trademark action. In the complaint that they filed in August, Amazon and KF Beauty claim that four companies and 16 individuals are on the hook for selling counterfeit versions of KF Beauty’s WUNDER2 beauty products, including its best-selling WUNDERBROW eyebrow gels, on Amazon’s sweeping third-party marketplace site.

That same month, Amazon also filed suit – along with stroller and travel accessories company J.L. Childress – against almost a dozen different Amazon-seller defendants on counterfeiting grounds. According to their complaint, Amazon and J.L. Childress argued that the defendants “willfully deceived and harmed Amazon, J.L. Childress, and their customers, compromising the integrity of Amazon’s stores, and undermined the trust that customers place [in them].”

Amazon went on to sue influencers Kelly Fitzpatrick and Sabrina Kelly-Krejci, along with 11 Amazon marketplace sellers in November for the “unlawful and expressly prohibited advertisement, promotion, and/or sale of counterfeit luxury products on Amazon.com” in violation of Amazon’s policies, and federal and state law. And still yet, Amazon and YETI filed suit against Michael White and Karen White, a couple of California-based Amazon sellers, in December for allegedly offering up counterfeit Yeti products on Amazon’s marketplace and ignoring cease and desist letters from the cooler company.

As for what is driving Amazon’s increased legal action: such activity is likely based to a notable extent on optics; the Jeff Bezos-founded company – likely taking a page from Alibaba’s transformation of its Tmall site, which is now home to luxury goods purveyors and their offerings – is looking to lure brands to list their products on its marketplace, including its newly-unveiled Luxury Stores, and at the same time, it is aiming to entice consumers to view it as a trustworthy source of goods.

Liability in the Internet Age

In the midst of its attempts to reposition itself in the eyes of brands and deep-pocketed consumers, Amazon is also ending up on the receiving end of a growing number of lawsuits of its own, albeit ones that largely come in the context of defective products – from hoverboards to dog leashes, which are prompting courts across the U.S. to consider the question of whether Amazon should be held responsible for its vendors’ products.

“With two notable recent exceptions, courts have gone along, absolving Amazon of liability,” the Wall Street Journal noted in February 2020. In the last Amazon liability decision of 2020, the Ninth Circuit followed that same trend, holding in the State Farm v. Amazon case that “Amazon provides a website for third-party sellers and facilitates sales for those sellers, [but] it is not a ‘seller’ under Arizona’s strict liability law for the third-party hoverboard sales at issue here.”

So, while Amazon has, in fact, garnered attention for the striking rise of fakes on its site, most of the headline-making cases that Amazon is facing do not center on counterfeits. Given the sheer volume of counterfeit or otherwise infringing goods on its site, which is evidenced – to some extent – by the lawsuits increasingly being filed by Amazon, and which has been largely attributed to the e-commerce titan’s 2014 decision to enable Chinese sellers to list on its marketplace, why is Amazon not facing more trademark-centric lawsuits?

Put another way, “How is Amazon able to continue allowing the sale of counterfeit goods with impunity?,” as Burns Levinson partner Mark Schonfeld put it. The answer, he says, “lies in a 2010 case brought by Tiffany & Co. against eBay,” in which Tiffany unsuccessfully accused eBay of trademark infringement on that basis that more than 70 percent of the Tiffany goods sold on eBay were counterfeit.

In response to Tiffany’s argument that eBay had a responsibility to police its website to prevent the sale of counterfeit Tiffany goods, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit determined that eBay was not liable for trademark infringement because eBay had a program in place to remove the sales of counterfeit goods upon request by the brand owner. Also significant: the curt fund that eBay did not possess the level of knowledge necessary for a finding of contributory trademark infringement. (The proprietor of an online marketplace must have “more than general knowledge” that its site is being used by third parties to sell counterfeit goods).

And with that (and in light of a cert refusal from the Supreme Court), the marketplace was off the hook for contributory trademark infringement, and walked away with what has been repeatedly characterized with a significant win for itself and for other website operators.

But are Amazon’s operations so perfectly analogous to eBay’s that the Second Circuit’s decision continues to be neatly applicable?

More recently than the Tiffany v. eBay case, Amazon prevailed when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed the lower’s court’s decision that Amazon was not liable for trademark infringement – or for patent or copyright infringement either – in connection with third party marketplace vendors’ sale of fake Milo & Gabby pillowcases. In that case, the district court dismissed Milo & Gabby’s trademark infringement claim on summary judgment because “the evidence demonstrates that Amazon is not the seller of the alleged infringing products.”

However, the ground may be shifting as courts examine issues of where liability lies in the digital economy.

“Amazon does a lot more to broker the arrangements between buyers and sellers than eBay has ever done,” Eric Goldman, a professor at the Santa Clara University School of Law, told Modern Retail last year. “Things like taking possession of the goods” – and then also processing the payment for them, packaging and shipping them, etc. – “puts Amazon in a qualitatively different place than eBay has ever been.”

eBay, itself, “emphasized the differences between [its] business model and Amazon’s,” Reuters wrote this summer. In connection with a now-defunct California bill – AB 3262 – which aimed to “make it easier for consumers to hold electronic retailers responsible for allowing defective products to reach the marketplace,” eBay and Etsy, too, argued in a joint letter in August that “they do not have warehouses to store products from outside vendors, they do not act as go-betweens for buyers and sellers and they do not ship products,” and thus, their buyers, “unlike Amazon buyers, should have no reasonable expectation that they are acting as sellers or retailers.”

And at least some courts are actively narrowing the applicability of the tenets of Tiffany v. eBay. In an April 2020 decision in the Chanel v. The RealReal (“TRR”) case, Judge Vernon S. Broderick of the U.S. District court for the Southern District of New York held that TRR’s operations are distinct from those of eBay, despite what arguments to the contrary from the luxury consignment company.

As distinct from the Second Circuit’s finding in Tiffany v. eBay, Judge Broderick held in April 2020 in response to TRR’s motion for summary judgment that the luxury reseller may be liable for infringement in connection with the sale of allegedly counterfeit goods on its site because while it does not take title to the merchandise that it sells, it does take physical possession and maintains an inventory of the merchandise (in much the same way as Amazon), and all the while “retain[s] the power to reject for sale, set prices, and create marketing for goods.”

In other words, “Unlike eBay, it is more than a platform for the sale of goods by vendors.”

“By adopting a business model in which it controls a secondary market for trademarked luxury goods, and by curating the products offered through that market and defining the terms on which customers can purchase those products, [TRR] reaps substantial benefit,” the Judge held, referencing specific divergences from eBay’s strictly sales-platform site. “As a result of this business model, [TRR] must bear the corresponding burden of the potential liability stemming from its ‘sale, offering for sale, distribution, [and] advertising of’ the goods in the market it has created.”

These issues are expected to continue to play out in courts across the U.S. in connection with the product liability cases that Amazon continues to face, as “the issue of liability when it comes to defective products is not completely removed from counterfeit liability,” according to Proskauer Rose’s Jeffrey Warshafsky, who states that how the issue of liability plays out “may have ripple effects beyond the realm of product liability cases.”