The striking rise in demand for non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) has captivated a growing pool of creators, consumers, and brands, and one of the immediate ramifications of that – aside from eye-watering sales, such as the millions of dollars that Beeple works and CryptoPunks have commanded – is the reality that NFT marketplaces are facing off against a perfect storm of fakes. One need not look further than the OpenSea and similar marketplaces to see how a sizable number of NFT creators are minting unique digital tokens tied to others’ art works and trademarks, and offering them up for sale, resulting in allegations of trademark and/or copyright infringement and in some cases, counterfeiting, from parties ranging from artists to famed luxury goods brands.

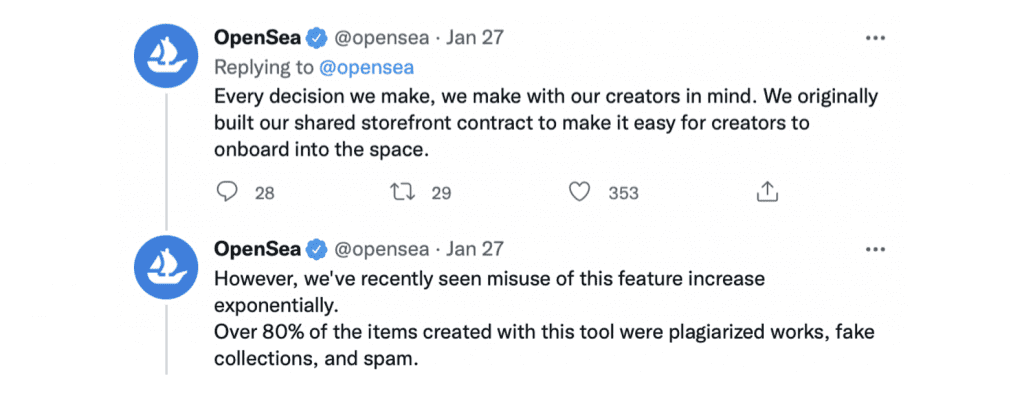

Shedding light on the issue of infringement when it comes to the explosive rise of NFTs, OpenSea stated in a string of tweets in January that it has experienced a “exponential” increase in “misuse” of its free minting tool, and that “more than 80 percent of the items created with this tool were plagiarized works, fake collections, and spam.” Reports from the likes of the Verge further expose the issue, recently revealing, for example, that artist Aja Trier’s viral Vincent Van Gogh-style paintings have been turned into nearly 86,000 NFTs – all without her involvement or authorization. And as TFL reported last year, platforms were being inundated with NFTs bearing the branding of others (from Chanel to Supreme), without the companies’ involvement or authorization.

Speaking about the surge in problematic offerings on Cent, the platform that he co-founded in 2017 and that played host to the sale of an NFT of Jack Dorsey’s first tweet for $2.9 million back in March 2021, Cameron Hejazi told Reuters that the sale of certain NFTs – namely, ones that consist of “unauthorized copies of other NFTs,” “content that does not belong to them,” and “sets of NFTs which resemble a security” – is a “fundamental problem” in the fast-growing digital assets market.

Shortcomings in the Law?

Interestingly, a fair share of the media narrative surrounding the increasingly rampant infringement within the so-called metaverse has suggested that some of the surge may be due to shortcomings in the law. The Wall Street Journal, for instance, recently stated that “government policies haven’t caught up to this technology, so it isn’t entirely clear what legal consequences there might be for someone who creates an NFT of someone else’s art.” While there is undoubtedly plenty of gray area at play when it comes to the law and the metaverse, a lack of applicability of existing intellectual property laws and policy does not appear (to me, at least) to be at the heart of what is going on here.

As the WSJ correctly notes, and as no small number of listings on NFT platforms indicate, “It is possible for anyone to make an NFT of any image or video, even if he or she doesn’t own the copyright for the image.” The same is true for the unauthorized use of another party’s trademark-protected name, logo, or other source-identifying symbol, by way of an NFT, as well as the unapproved use of another’s likeness, which is generally protected via states’ right of publicity laws.

However, the fact that NFTs can be minted and tied to others’ intellectual property does not necessarily mean that existing law does not apply and that the resulting product falls within the bounds of the law. (This is where there is room for discussion about what the product at issue actually is and what role the NFT plays.)

Despite the narrative that the metaverse is a “Wild West” in which anyone can co-opt another’s copyright-protected works or trademark-protected branding and link them to an NFT, the reality can be quite different. “If the NFT-linked work is an exact copy of a copyrighted work or it constitutes an unauthorized derivative work,” for example, Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP attorneys Anastasia Dergacheva and Christopher Archer assert that “the copyright owner may assert infringement on the basis that a copy was made to generate, display, or promote the NFT, or some other exclusive right of the copyright owner was violated.” As such, they state that “the person or entity minting the NFT must either own the underlying asset or have the necessary rights to mint and sell the NFT.”

On the trademark front, use of another party’s trademark in connection with an NFT could give rise to infringement claims in the event that consumers are likely to be confused about the source or sponsorship of the NFT, and assuming that the trademark asserting party has rights in the mark when it comes to virtual goods/NFTs.

Or a Problem with NFT Marketplaces?

More than signifying critical issues with existing trademark or copyright laws (which apply to uses in the digital realm and likely are not fundamentally unable to provide protection for and enforcement against assets tied to NFTs, as well as other virtual goods/services), the proliferation of NFTs tied to allegedly infringing works seems to more clearly indicate NFT marketplaces’ inability to prepare for and subsequently address the sheer spike in minting and sales transactions – including for allegedly infringing works – that have taken place over the past year.

(To put growth in the NFT space – which is on track to blossom into a $80 billion market by 2025, according to projections from Jefferies – into perspective, OpenSea, which nabbed a $13.3 billion valuation in January after closing a $300 million Series C round, boasted a transaction volume that surpassed $14 billion for 2021, up from $27.1 million in 2020. After doing more volume in sales during two days in August 2021 (a total of $95 million) than it did in all of 2020, OpenSea co-founder and CEO Devin Finzer stated on Twitter this past summer what has become perfectly clear over the past year: “The growth curve for NFTs is insane.”)

Primarily, the issue appears to be that platforms that enable individuals to list – and oftentimes, mint – NFTs generally enable those individuals to list NFTs without employing meaningful screens for potential infringements. Second, there seems to be a lack of effective enforcement of the platforms by the platform operators. In actuality, most of these NFT marketplaces have relied almost exclusively on reactive measures when dealing with allegedly infringing works. In other words, the marketplaces are largely policed by rights-holders, themselves, who file notice and takedown requests in order to have (allegedly) infringing materials removed.

Notice and takedown procedures are not in any way unique or limited to NFT marketplaces; the existence of a robust takedown system helped eBay to sidestep liability in the trademark case filed against it by Tiffany & Co. more than a decade ago. Not a perfect solution, rights-holders have accused platforms like OpenSea of failing to act on takedown requests in a timely manner (or to act at all in some cases). In other instances, creators have complained that even when allegedly infringing listings are removed, new ones pop up in their place, mirroring the game of whack-a-mole that rights-holders are forced to play when it comes to listings of tangible counterfeit or otherwise infringing goods offered up on established marketplaces and/or by way of third-party domains.

OpenSea revealed recently that it is “working through a number of solutions to ensure we support our creators while deterring bad actors,” and at the same time, a rep for the company told the WSJ that will be “hiring dozens of employees to deal with infringement and security problems in the coming months.” Meanwhile, in an even more aggressive move to put a stop to the sale of infringing NFTs, Cent has “halted most [NFT-related] transactions because people were selling tokens of content that did not belong to them.”

Consumers & Contributory Liability

As for what is prompting marketplaces to take increased action, chances are, it is due, at least in part, to their desire to hold on to existing users and attract news ones, something that would likely be difficult to do if a lack of enforcement against copycat NFTs starts to chip away at trust in such platforms in a meaningful way. (The stakes are of, course, higher given the decentralized nature and irreversibility of the transactions – even if the goods at issue are not above-board in a legal sense.

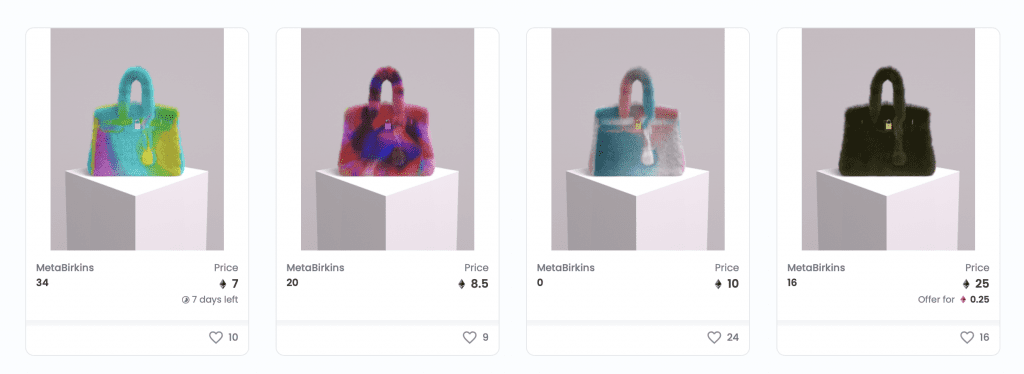

There is also the potential for liability for platform operators in light of the influx of allegedly infringing listings on their sites. While Hermès, for instance, did not name OpenSea, Rarible, or LooksRare – the platforms upon which the allegedly infringing and diluting MetaBirkins NFTs have been made available – as defendants in its lawsuit against MetaBirkins creator Mason Rothschild, the potential for contributory liability for platforms is not impossible to imagine.

“In some cases, a rights-holder may have a claim against the marketplace operators for contributory liability of it can show that she marketplace was aware of the infringing activity, and induced, cause, or materially contributed to the activity,” according to Skadden attorneys Stuart Levi, Eytan Fisch, and Alex Drylewski. Given the active role that many marketplaces play in enabling individuals to create and offer up of NFTs (OpenSea’s since-discontinued free minting tool comes to mind), they assert that “the second prong could be easy to establish.”

On the contributory liability front, the Skadden lawyers suggest that a plaintiff could “analogize today’s NFT marketplaces to those of a swap meet operator” like the defendant in the Fonovisa v. Cherry Auction case, in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held that a party that has “knowledge of the infringing activity, induces, causes or materially contributes to the infringing conduct of another, may be held liable as a ‘contributory’ infringer.” However, it is worth noting that in order to successfully establish knowledge (and secondary liability more broadly), a plaintiff would need to demonstrate that the defendant marketplace has knowledge of “specific infringing material,” which can vary depending on “the type of infringing activity, the nature of the services used by the direct infringer and provided by the online provider, and the online provider’s control over those services.”

THE BOTTOM LINE: Lawsuits will continue to be filed by brands and other rights-holders, as the NFT market shows no signs of subsiding. Given that the identity of NFT-makers may be difficult to discern in no small number of instances (thereby, potentially taking some remedies off the table for rights-holders) , increasingly-valuable and easily-identifiable marketplaces are likely to be an attractive target, which is almost certainly part of why they are increasingly taking action to address allegations of infringement and limiting their involvement beyond acting as pure marketplaces.