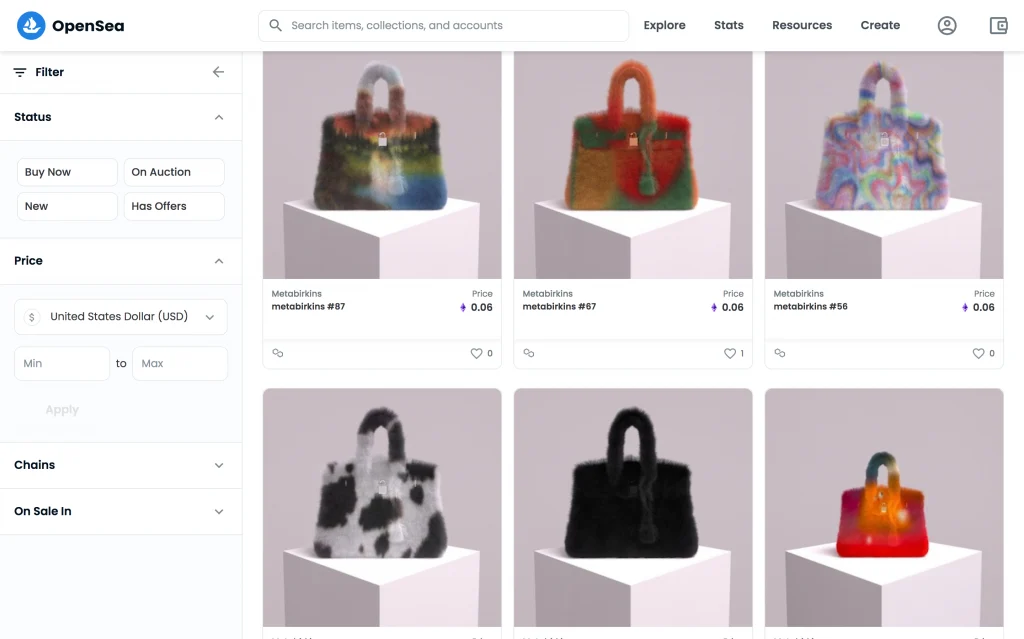

Amid the trial that is currently underway before a jury in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, in which Hermès is accusing Mason Rothschild of infringing and diluting its famed Birkin trademark and trade dress by way of a collection of “MetaBirkins” NFTs tied to imagery that depicts fur-covered Birkin bags, the court has reaffirmed an earlier order refusing to grant either Hermès or Rothschild’s motions for summary judgment. Following from a brief order last month, Judge Jed Rakoff has set out the reasoning for his denials, and shed light on an array of interesting elements from the parties’ discovery, including Rothschild’s alleged plans to make additional meta-titled NFTs, including, “MetaPateks.”

In furtherance of their motions for summary judgment, Judge Rakoff states that Hermès and Rothschild asked the court to determine two questions: (1) Whether the digital images underlying the MetaBirkins NFTs should be evaluated under the Rogers v. Grimaldi test for artistic works or the Gruner + Jahr test for general trademark infringement; and (2) whether, under whichever test is applied, the MetaBirkins NFT images or related products infringe and/or dilute Hermès’ trademarks pertaining to its Birkin handbag.

As to the first, “threshold question,” the court reaffirms the determination it made in its May 2022 order, in which it stated that the plaintiffs’ claims should be assessed under the Rogers test, noting that “courts in this circuit and elsewhere have long applied a two- tiered approach to trademark infringement claims” when the alleged infringement involves works of “artistic expression.” Judge Rakoff says that the gist of fellow district courts’ holdings is that “as long as the plaintiff’s trademark is used to further plausibly expressive purposes, and not to mislead consumers about the origin of a product or suggest that the plaintiff endorsed or is affiliated with it, the First Amendment protects that use.”

Hermès has argued that that because “Rothschild had no discernable artistic intent or expression in promoting and selling [the MetaBirkins NFTs],” the Gruner test should apply. In arguing its position, Hermès points to evidence of actual confusion, as well as evidence “from which a reasonable juror could conclude that Rothschild’s claims that he viewed MetaBirkins as a largely artistic endeavor is a fabrication.”

For instance, Hermès relies on evidence in which Rothschild – in discussions with investors – “observed that ‘he doesn’t think people realize how much you can get away with in art by saying ‘in the style of’ and boasted that he was ‘in the rare position to bully a multi-billion-dollar corp[oration].’” Additionally, Hermès put forth a text message in which “Rothschild told associates that he wanted to make ‘big money’ by ‘capital[izing] on the hype’ in the media generated for the [MetaBirkins] collection.” Hermès argues that these comments “are probative of an intent to exploit [the reputation of the Hermès Birkin marks],” and that Rothschild “invoked the First Amendment as a defense only after it had sent [him] a cease-and-desist letter.”

Unpersuaded, Judge Rakoff contends that “such evidence does little more than show that Rothschild’s project was driven in part by pecuniary motives, a fact that does not bar application of the Rogers test.”

Rothschild, on the other hand, has consistently asserted that “the project’s expressive purpose was clear from its inception.” Specifically, the MetaBirkins NFTs are “‘part of [an] artistic experiment to see how people with money and influence who drive the culture would respond to’ the MetaBirkins and ‘whether they actually would ascribe value to the ephemeral MetaBirkins” in the same way they attached value to the physical Birkin bags.”

Ultimately, the court states – and the currently-pending trial centers on the fact – that there is “a genuine factual dispute as to whether Rothschild’s decision to center his work around the Birkin bag stemmed from genuine artistic expression or, rather, from an unlawful intent to cash in on a highly exclusive and uniquely valuable brand name.” Because “reasonable individuals could reach different conclusions on the ‘artistic relevance” factor,’” the court denied both parties’ summary judgment motions on that front.

Turning to the issue of whether Rothschild’s MetaBirkins are “explicitly misleading,” the court states that the parties “disagree vehemently over whether consumers were confused about Hermès’ association with the MetaBirkins project,” which is just one of the Polaroid factors. Because there remain “substantial factual disagreements between the parties with respect to many – if not most – of the eight factors, any of which could be dispositive to the outcome,” the court similarly declined to grant summary judgment for either party on this issue.

An additional point worth noting: Judge Rakoff delves into what the works at issue are “from the perspective of the prospective consumer,” stating that “individuals do not purchase NFTs to own a ‘digital deed’ divorced from any other asset: they buy them precisely so that they can exclusively own the content associated with the NFT.” More than that, he states that “undisputed evidence in the record indicates that consumers did in fact understand themselves to be purchasing exclusive ownership of the digital image alongside the NFT.”

Some Discovery Takeaways

By way of some background, the court’s order shed light on some interesting elements that were uncovered during discovery in the case …

– Rothschild considered creating more than the first 100 MetaBirkins NFTs. According to the order, “Rothschild contemplated ‘minting’ more MetaBirkins NFTs to sell.” In conversations with his associate, Mark Berden, Rothschild remarked that they “should consider producing upward to nine hundred, adding that the profits of these newly minted NFTs should be divided between the two, with $400,000 going to Rothschild and $100,000 to Berden.”

– “Rothschild also discussed [with his associates] potential future digital projects centered on luxury products, such as watch NFTs called ‘MetaPateks’ that would be modeled after the famous watches produced by Patek Philippe.”

– Hermès asserts that Rothschild’s project has “disrupted [its] efforts to enter the NFT market and hindered its ability to profit in that space from the Birkin bag’s well-known reputation … Indeed, the company alleges that it has for years developed potential uses for NFTs as part of its overall business strategy. Rothschild’s efforts to crowd it out of the NFT market, Hermès claims, places it at a competitive disadvantage: its plans to enter this market follow on the efforts of several top fashion brands to develop NFT strategies that would allow them to market their goods to a wider audience.”

– There is substantial disagreement between the parties as to whether Rothschild himself created the digital images associated with the MetaBirkins project or whether another artist – Mark Berden – was responsible for designing and rendering them. (The court has stated that this dispute is “legally irrelevant so far as the instant motions are concerned. Whether there is admissible evidence that the MetaBirkins are art – and therefore, whether the Rogers test should apply – does not turn on who designed the NFTs.”)

The case is Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, 1:22-cv-00384 (SDNY).