image: Vogue Arabia

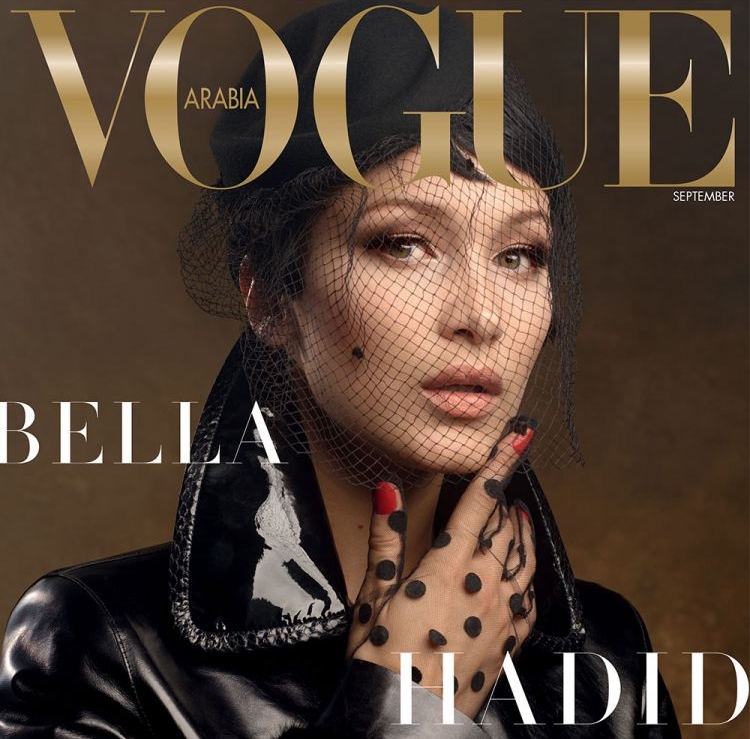

After the abrupt ousting of Deena Aljuhani Abdelaziz, who served as the editor-in-chief of newly-launched Vogue Arabia before being fired after the release of only two issues, Vogue Arabia’s September issue is here. Under the creative control of brand new editor-in-chief Manuel Arnaut, who formerly held the same role at Architectural Digest Middle East, the magazine has put forth an interesting first cover, one that amounts more to an advertisement than an editorial.

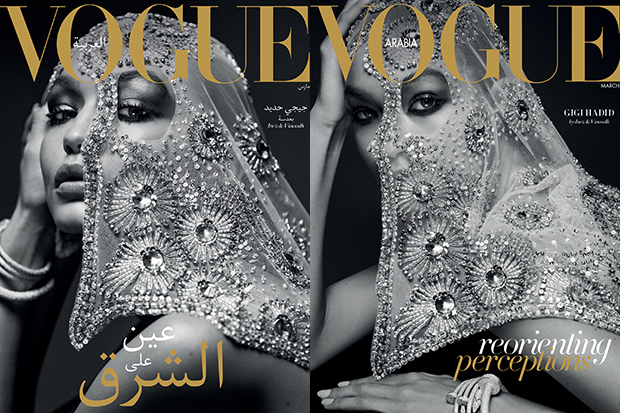

On the heels of her sister Gigi Hadid gracing the first-ever cover of Vogue Arabia in March (yes, fashion is really running with the Hadids’ Muslim roots), Bella Hadid appears on the September cover dressed in Fendi and photographed by Karl Lagerfeld.

While not out of the ordinary on its face, this cover – and the circumstances that surround it – becomes interesting if we consider a few facts.

First: Cover star Bella Hadid is the current face of Fendi; she appeared in the Italian design house’s most recently-released ad campaign. Second: Karl Lagerfeld, who photographed the cover and corresponding editorial, is the creative director of Fendi’s womenswear collection. Third: Hadid is styled in head-to-toe Fall/Winter 2017 Fendi (which is conveniently in stores right now in case you are tempted by the editorial) for the cover and corresponding editorial. And lastly, let us not overlook the fact that Fendi spends big advertising dollars to appear in Conde Nast publications – Vogue Arabia certainly falls under that umbrella.

While none of these elements are inherently problematic, when taken together, the cover and corresponding editorial seems to reek of exactly the type of murky dealings that former British Vogue director Lucinda Chambers highlighted last month in a particularly telling excerpt of her interview with Vestoj magazine. That specific excerpt spoke to Vogue’s preferential treatment of advertisers. Chambers said, “The June cover with Alexa Chung in a stupid Michael Kors T-shirt is crap. He’s a big advertiser, so I knew why I had to do it.”

This is not the only example we have. Remember the internal Harper’s BAZAAR document that made the rounds online several years ago? As first published by Racked in November 2010, the document listed the brands to feature in upcoming editorial spreads, ranked according to priority — and helpfully divided between “Advertisers” and “Non-Advertisers,” suggesting that advertiser status does, in fact, impact editorial decisions in some form.

A more recent example that seems to suggest that publications give preferable treatment to advertisers: BoF’s “The 16 Best Companies to Work for in Fashion 2017” list. The vast majority – if not all – of the companies that appear on BoF’s highly-promoted “Best Companies” list are active and in many cases, longstanding, advertisers on the publication’s site. That list did not, at the time of publication, disclose that it primarily consists of and serves to promote BoF advertisers.

This preference for advertisers is certainly not new practice within the fashion industry, but nonetheless, feels, for lack of a better word, icky, due to the lack of transparency that comes along with it. Read: The average consumer – the ones that both advertising laws and journalistic ethics standards aim to protect – would otherwise have no idea about it.

As for whether such preferential treatment – which would, of course, be rather difficult for a government regulator or industry watchdog to prove in many cases – gives rise to legal and/or ethical concerns, you can count on it.

The guidelines of the Federal Trade Commission, alone, which require disclosure of “material” relationships between parties, seem to apply quite neatly here. As for why that agency has allowed fashion to get away with such large scale tactics – which could quite easily amount to deceptive advertising in accordance with its standards – for so long, that is another matter entirely. It does, however, make its recently initiated fight against influencers seem a bit one-sided.