LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton completed its $15.8 billion mega-deal to buy famous American jewelry giant Tiffany & Co. late last month. The French luxury goods conglomerate – which owns Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Celine, Fendi, and Givenchy, among 70-or-so other luxury brands – originally agreed to pay $16.2 billion for New York-headquartered Tiffany in 2019, but when the market sufficiently changed thanks to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was able to talk down the premium.

That is just one example of the fire that the global health pandemic has ignited in many industries. There has been a surge in global mergers and acquisitions since the second half of 2020 as the strong snap up the weak. Driven by the tech, media, entertainment and telecoms sectors, total deals for the year were worth $2.9 trillion. Recent moves include Ladbrokes Coral owner Entain’s £250 million takeover of Swedish gaming group Enlabs, and U.S. group Alden Global Capital’s $520 million bid to take full control of Tribune Publishing, owner of the Chicago Tribune. As no shortage of media outlets have proclaimed in recent weeks, this trend looks likely to snowball in the coming months. But what does this actually mean?

Houses of Cards

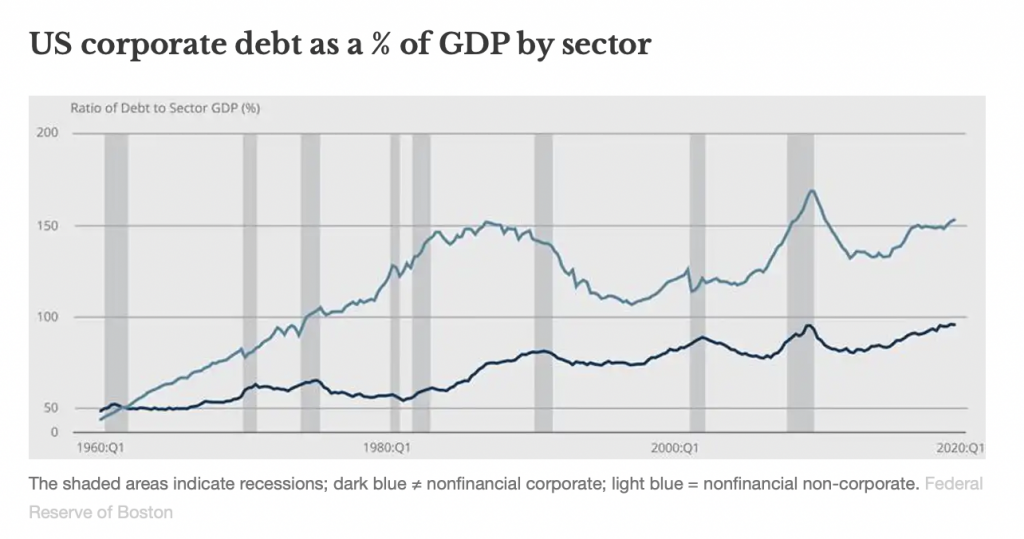

The reality of the market is that many firms were vulnerable even before the pandemic. For over a decade, low – or sometimes negative – interest rates had driven businesses to reduce their rainy-day cash holdings and embark on a borrowing spree that left them heavily indebted. The default strategy in advanced economies like in North America and Europe was often to maximize leverage – meaning to borrow as much as possible from banks and the markets to try and maximize returns from the capital employed. You can see in the graph below how leverage has steadily increased over the decades in the US, for instance.

But in the low-growth environment since the 2008-09 financial crisis, times have been hard. Many companies experienced disappointing returns and rising portions of profits being diverted towards interest payments, which left many businesses cash-strapped and unable to invest. This further weakened their profitability – in many cases turning them into zombie companies that would be put out of their misery when credit conditions tightened.

Many companies swapped long-term stability for short-term gains, relying on financial schemes with high hidden risks. For example, companies increasingly borrowed to buy back their own stock for an immediate uptick in the share price. With management teams often paid partly in share options, they had a personal financial interest in this strategy.

Life Support

When COVID panic set in last spring, it threatened a financial crisis caused by corporate bonds being dumped by the markets. This could have driven up interest payments to ruinous levels and caused many corporate collapses. Central banks responded with a major new round of quantitative easing (“QE”), expanding the supply of money to effectively put a floor under bond prices. They then did more QE later in the year. This kept many firms afloat, but pandemic lockdowns have also jeopardized many business models. The long buoyant conditions that many took for granted are gone. Low on cash reserves and buried by debt, companies in industries like hospitality or airlines, and manufacturers whose supply chains have been shredded, have joined the zombie hordes.

Numerous governments have tweaked laws to keep companies on life support. For example, Germany relaxed the rules around over-indebted companies filing for insolvency. Meanwhile, banks have made credit lines and interest payments flexible to allow companies to hang in there. And companies have been issuing new corporate bonds at record levels to get the cash to survive. But in the end, collapses are often unavoidable.

Distress, distress, distress

Against that background, we are seeing three kinds of distress: owners, lenders and buyers. When owners cannot keep their cash flows positive, are refused cheap loans, or are forced to accept higher loan rates on existing debt, they often fail. It happens to listed and privately held companies alike, and even those with strong underlying assets can get into trouble. They must either restructure debts, find a buyer or do both.

Lenders are under pressure, too. Corporate bondholders face being left with worthless bonds. Banks must decide whether they believe in a company’s ability to pay back their loans or to accept less than the full payment and get the debt off their books. Having just cleaned up their bad loans following the global financial crisis of 2008-09, they will be experiencing a bad case of deja vu. In many cases, banks are being asked to accept less as part of a takeover. Just like the Tiffany shareholders must have concluded in the LVMH deal, it is often better to have an end with horror than a horror without end.

For buyers, companies with good assets that are insolvent only because of the crisis can be a smart acquisition. Bloomberg is to raise $1 billion to acquire prime commercial real estate from distressed sellers, for instance. But many buyers are pushed to the negotiating table. Rather than seeing key suppliers sink, doing a deal that incorporates them into your business is often preferable. Otherwise your competitor might do the deal instead, threatening your competitiveness and bottom line.

It is in the interests of all three groups to survive the current crisis by negotiating compromises, so a huge wave of mergers and acquisitions is inevitable in 2021. This boom will touch many people in society. Perhaps the most important reason why governments and central banks have been keeping zombies from going under is to prevent massive layoffs. When these distressed companies are bought and restructured, it will likely cost many people their jobs and force them to search elsewhere.

Yet at the same time, some employees will enjoy career advances by striving in the rejuvenated subsidiaries of new parent companies. M&A can also be a relief for taxpayers if zombies no longer waste valuable public resources that can be used more efficiently elsewhere. In short, more change is coming. It will produce winners and losers, but it is better to expect it than be taken by surprise.

Patrick Reinmoeller is a Professor of Strategy and Innovation at the International Institute for Management Development.

Karl Schmedders is a Professor of Finance at the International Institute for Management Development.