“Last year, millennials unknowingly spent $482 million on counterfeits on Black Friday, [with] one in four likely to fall for counterfeits due to their inability to spot fakes online.” That is what digital IP infringement detection and removal firm Red Points stated in the market research report it released ahead of Black Friday in 2018. While younger demographics of consumers are not immune to being duped into buying counterfeit goods online, if TikTok is any indication, many young consumers are actively seeking out counterfeits, making videos dedicated to finding fakes a top type of content on the video-sharing social media site.

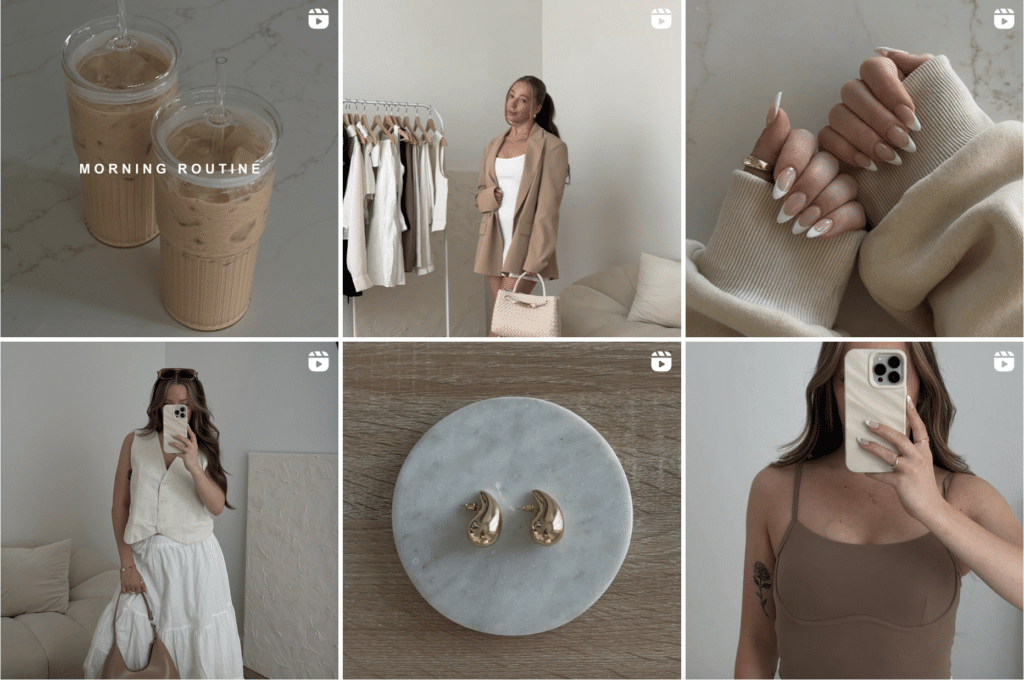

According to a recent report from CNBC, “A major video genre on TikTok is videos on finding” – and proudly showcasing – items conveniently (albeit erroneously) labeled as “dupes.” Realistically, these items are not “dupes,” a term used to refer to legally above-board products that take inspiration from other, existing (and often much more expensive) products, from fast fashion garments to buzzy makeup and skincare products. Instead, these products, which make unauthorized use of brands’ names and other legally-protected trademarks, are trademark infringing and/or counterfeit goods).

CNBC notes that most of these items, which “look like [those coming from] Chanel, Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Cartier or other pricey designers, can be found on sites like DHGate, AliExpress or Amazon.” And in addition to luxury labels, activewear brand Lululemon and teen-focused retailer Brandy Melville populate the list of names for which TikTok stars are providing their followers with “dupes” for in furtherance of a larger trend in light of the fact that “many younger consumers are cost-conscious but also photographed at a dizzying rate.”

A Larger Trend

These findings – and the larger trend of “dupe”-centric TikTok videos – coincide with those reflected in a 2019 report from the International Trademark Association (“INTA”), which polled 1250 American consumers between the ages of 18 and 23 and uncovered some telling insights on the state of the counterfeit economy. Among the striking takeaways from INTA’s report: 71 perfect of Gen Z-ers in the U.S. had purchased a counterfeit good over the past year, with apparel and footwear being among the most-purchased types of fakes.

As for why – exactly – these consumers are driven to purchasing counterfeit goods (i.e., ones that are “exact imitations of a brand’s product and its packaging”) in the specified year-long period, INTA discovered that 73 percent of the American consumers surveyed said that such purchases are driven, at least in part, by the fact that they “feel they cannot afford the lifestyle they want.” And of those consumers, only 35 percent said that they “expected to purchase fewer counterfeit products in the future.”

Pointing to one specific example, CNBC cites Holly Yazdi, an 18-year-old high school senior from Alabama, who counts “dupe” videos among her most heavily-viewed posts on TikTik. “A video of how to buy an Amazon dupe of Cartier’s $1,650 yellow-gold ‘Love Ring’ for less than $20” is her most popular post, per CNBC, with “other videos including [where to find] lookalike Gucci boots ($89 for the dupe; $1,190 for the real thing).”

While social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram have explicit policies that prohibit users from selling and promoting counterfeits and otherwise infringing products, it is unclear, CNBC states, what TikTik’s official policy is for posts like this, the 3-year old Beijing-based company, which boasted more than 1 billion users as of February, “could potentially be liable if lots of users are directing other users to the sales of dupes. As for who else could be liable, the e-commerce marketplaces offering up these so-called “dupes,” a term that is used interchangeably with legal term of art, namely, counterfeits and trademark infringements.

There is also a chance that the individual TikTok users, themselves, could be liable from a secondary perspective given that in an attempt address the difficulty that exists in stopping counterfeiters online, at least some intellectual property owners have tried and “will continue to try to expand the boundaries of secondary liability by suing parties involved in some manner in the sale, advertising, payment, shipment or other activities relating to such goods,” according to Lewis Roca partner Michael J. McCue.

After all, 15 U.S.C. § 1114 sets out that “any person who shall … be liable in a civil action” if he/she “use[s] in commerce any reproduction, counterfeit, copy, or colorable imitation of a registered mark in connection with the sale, offering for sale, distribution, or advertising of any goods or services on or in connection with which such use is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive.”

The idea of establishing secondary liability in connection with the promotion of counterfeits is not entirely novel. As Tiffany & Co. argued (albeit unsuccessfully) in the heavily-cited case that it filed against eBay in connection with the sale of counterfeit goods, eBay not only knew about the sale of counterfeit goods by third-parties on its marketplace and refused to stop these sales, but it actively promoted these products since it garnered fees for each sale of these counterfeit products.

From TikTok to Amazon

In light of such rampant availability of counterfeit or otherwise infringing products on its site and given increased pressure from the Trump administration, including a recent U.S. Department of Homeland Security report centering on the role of marketplace sites in the sale of counterfeit goods, Amazon is reportedly readying a new program in which it will provide an increased amount of information about the sale of counterfeit goods on its platform to law enforcement in furtherance of its effort to cut down on fakes.

As for the brands, themselves, most have been reluctant to – or in the case of LVMH, have been openly opposed to – enter into a partnership with the likes of Amazon due, in part, to the presence of counterfeit goods on such sites, CNBC’s Megan Graham says that brands “have to decide whether to encourage the creativity of its fans,” including their penchant for making “dupes” by affixing brands’ trademark-protected logos to garments and accessories and posting videos of this on sites like TikTok, “or come off as buzzkills if they try to clamp down on the activity.”

“If you’re Chanel and you believe the only way to be Chanel is to sell thousand-dollar handbags, and you don’t at least take a look at what’s happening on TikTok or what’s happening in this generation, you [are being shortsighted] to what will make you relevant for generations to come,” says Katy Hornaday, chief creative officer at advertising agency Barkley.

But in reality, the decision that brands have to make are nearly non-existent when it comes to fans because brands do not tend to take legal action against individual consumers for buying and/or displaying fakes. This is not only because such actions come with a risk of public relations pushback, but because there is no legal basis for policing the buying and wearing of fakes in the U.S.; trademark infringement and counterfeiting liability rests, instead, with the manufacturers and/or sellers of counterfeit goods.

With that in mind, brands have focused almost exclusively on the sellers when it comes to counterfeit goods, with that pool being widened to e-commerce marketplace sites and other third-party actors, such as customs brokers and other import-related parties … but not consumers.