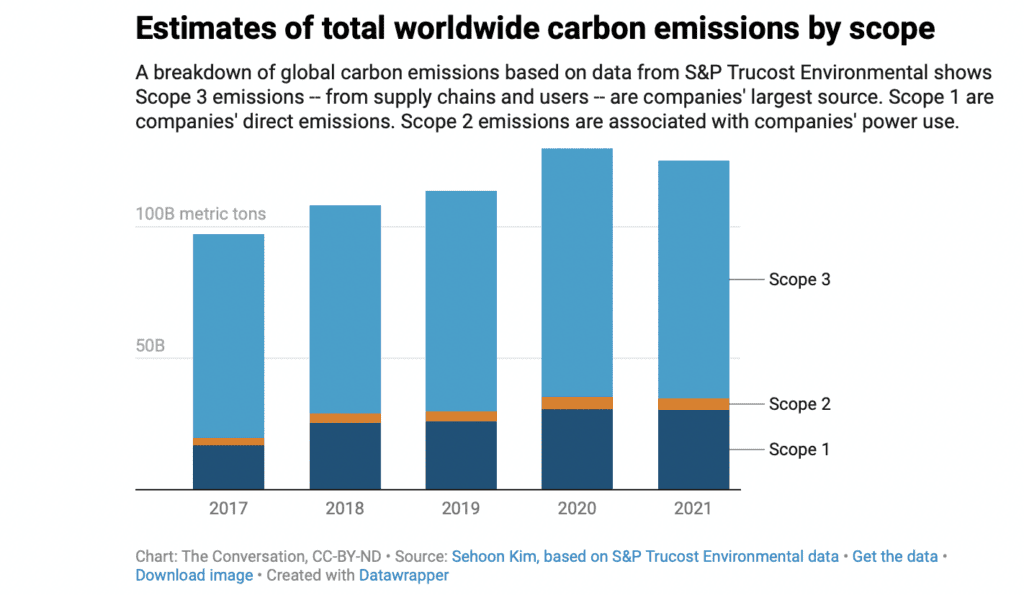

After two years of intense public debate, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission approved the nation’s first national climate disclosure rules on March 6, setting out requirements for publicly listed companies to report their climate-related risks and in some cases their greenhouse gas emissions. The new rules are much weaker than those originally proposed. Significantly, the SEC dropped a controversial plan to require companies to report Scope 3 emissions – emissions generated throughout the company’s supply chain and customers’ use of its products.

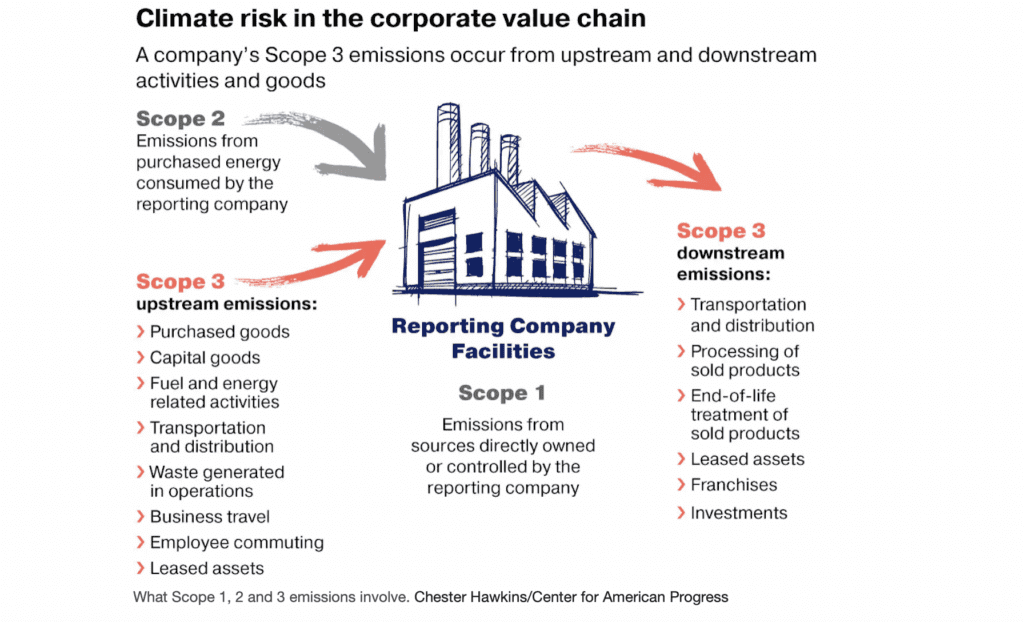

The rules do require larger companies to disclose Scope 1 and 2 emissions, which are emissions from their operations and energy use. But those disclosures are required only to the extent that the company believes the information would be financially “material” to a reasonable investor’s decision making. More broadly, the new rules require publicly listed companies to disclose climate-related risks that are likely to have a material impact on their business, as well as disclose how they are managing those risks and any related corporate targets.

After announcing its initial proposal in 2022, the SEC received a staggering number of comments from experts, companies and the public – about 24,000 of them, the most ever received for an SEC rule. The comments reflected both strong public interest in being informed about corporate climate-risk exposures and greenhouse gas emissions and also significant pushback, particularly over how much the rules would cost companies. Several Republican state attorneys general threatened to sue.

In response to the comments, the commissioners took their time to adjust the disclosure requirements, but the legal challenges may not be over. Against that background, here are some of the major issues that led to this change and the implications of the new disclosure rules as they phase in starting in 2025 …

The climate disclosure cost to companies

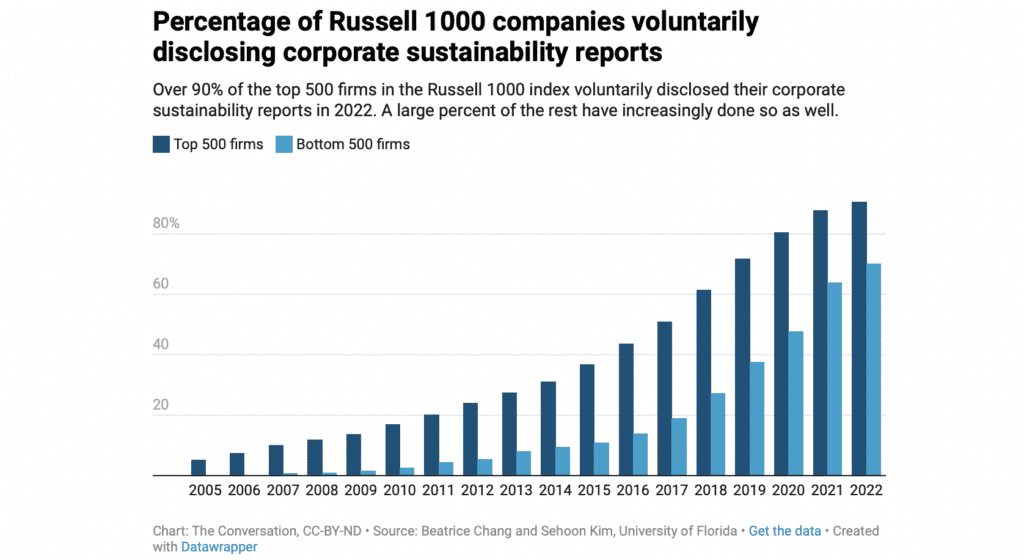

The most important reason for adding climate disclosure rules, as SEC Chairman Gary Gensler has noted, is that climate-related risks and greenhouse gas emissions appear to be financially material information demanded by investors. Indeed, for the past several years, large institutional investors have been vocal about the need for more transparency and consistency in corporate climate-risk disclosures.

As the SEC has often emphasized, most large companies already disclose some of this information voluntarily in their sustainability or ESG reports, which often are published alongside their annual reports. Since investors seem to demand this information, and many companies are voluntarily providing it, the SEC and proponents argued that it would be sensible to mandate some consistency in disclosures. However, much of the debate around the new disclosure rule has focused on whether it passes the cost-benefit smell test. In other words, would the compliance cost borne by firms potentially outweigh the financial benefits of mandated disclosures of climate risks and emissions that investors might value?

The compliance costs of federal disclosure requirements have been estimated to be substantial. When the SEC first proposed the rule in 2022, the commission’s own estimates implied that disclosure-related compliance costs would nearly double for the average publicly listed company.

Comments on the rule have since pointed out that there are also likely to be even greater indirect costs related to adjustments that companies might have to make in how they conduct their operations. These costs might also have broader implications for employment in certain jobs and sectors. Given that many smaller listed companies do not have voluntary disclosure practices in place, the burden is also expected to hit companies unequally, disproportionately affecting smaller companies while large corporations see little impact.

Measuring emissions isn’t simple

Another practical problem lies in enforcing consistent measurement of emissions and climate-risk exposure. International groups, such as the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures and the International Sustainability Standards Board, have provided reporting standards and guidelines. But the measurements themselves are still subject to estimation and collection problems that might vary across industries and activities.

Moreover, estimating Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions separately presents significant challenges. In particular, the difficulty of measuring a company’s indirect emissions from its supply chain – Scope 3 emissions – exponentially compounds the estimation problem. Reporting Scope 3 emissions also opens a floodgate of legal issues, as many smaller organizations in a large company’s value chain might have no legal obligation to disclose their own emissions.

The backlash over the challenges inherent in measuring Scope 3 emissions led to the commission’s decision to pare back that part of its proposed rules. Many companies will also likely have to outsource the estimation and quantification of emissions and climate risks to third-party companies, where there have been concerns about higher costs, conflicts of interest and greenwashing.

How SEC stacks up to California, EU rules

The SEC is not the first to adopt climate disclosure rules. A similar rule went into effect in the European Union in January 2024. California has an even more stringent rule, signed into law in October 2023. It will require both publicly listed and privately held firms to fully and unconditionally disclose all of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions when it goes into effect in 2026 and 2027. Since California is among the world’s largest economies, its regulations are already expected to have wide effects on corporations around the world.

Hardcore proponents of the SEC rule who wanted California-level disclosures across the board argue that Scope 3 emissions need to be disclosed given that they compose the largest fraction of all carbon emissions. Skeptics of the rule, including two of the five SEC commissioners, question whether there needs to be any rule at all if things are inevitably watered down anyway.

Given the recent conservative backlash against companies focusing on ESG issues and the ensuing retrenchment by several institutional investors from their previous climate commitments, it will be interesting to see how the new corporate climate disclosures will actually affect investors’ and corporations’ decisions.

Sehoon Kim is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Florida. (This article was initially published by The Conversation.)