Deep Dives

The past couple of months have demonstrated the enduring rise in fashion and luxury deals, the very ones that were expected to unfold in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fosun Fashion Group, for instance, acquired Sergio Rossi in June, and a week later, LVMH assumed the outstanding 33% stake in Emilio Pucci. This month, Swiss conglomerate Richemont took a 100 percent stake in Belgian luxury brand Delvaux, LVMH announced a minority stake in Phoebe Philo’s soon-to-launch eponymous label, L Catterton Europe revealed that it will acquire a majority stake in Etro (pictured above), and just yesterday, LVMH made headlines when it confirmed that it will buy a 60% in Off-White.

Much has been made of growing number of M&A transactions, with many rightly pointing to the effect that the pandemic has in bringing these deals into fruition. As Ermenegildo Zegna Group CEO Gildo Zegna noted this week in connection with news that the privately-held Italian fashion group will go public on the NYSE later this year via a merger with Investindustrial Acquisition Corp., a special purpose acquisition corporation, “The luxury business has become very challenging,” making it even more difficult for independent brands to compete. Low interest rates and excess cash on hand for the likes of LVMH, Kering, and co. have further spurred the trend.

To date, conversations have largely centered on the impetus for these tie-ups, the deals that may still in the making (An acquisition by Prada? A deal between Exor and Armani, despite recent reports to the contrary? The sale of Valentino?), and what this wave of consolidations means for the industry as a whole. One thing that has not been discussed with the same frequency is the topic of goodwill and brand equity, and how these are impacted by M&A activity, such as the deals that are currently underway.

Two heavily intertwined concepts, brand equity is the value premium that a company generates from a product with a recognizable name (or logo) compared to an equivalent. Goodwill, on the other hand, refers to the reputation that a company earns in the minds of consumers. Ultimately, both are dependent on the fact that a brand (and its value) is more than just a name or a logo.

Certainly, trademarks – from brand names and logos to source-identifying product configurations and packaging – are valuable and heavily monetizable assets for companies, especially in the fashion and luxury space, hence, the markup for logo-bearing luxury goods and the often-eye-watering valuations for brands in this segment of the market. Yet, the reason that brands’ names and other trademarks have such significant value is a direct result of the goodwill that they embody. This is built by brands over time (arguably less time than ever before thanks to the rise of e-commerce and social media) by consistently providing quality products and services, telling carefully-crafted stories by way of their marketing efforts, etc.

Given that trademarks depend, in large part, on things like goodwill in order to generate value for a company both in terms of day-to-day interactions with consumers, as well as in M&A scenarios, the influx of deals in the luxury space raises important questions about how goodwill may be impacted in the event of a sale, and if and again, how a company can maintain a brand’s goodwill – which is a big part of what it paid for, albeit indirectly – on the heels of an acquisition.

A review of the market reveals (at least) two common instances in which goodwill is potentially at risk: (1) instances in which a large conglomerate takes ownership of a company, and grows the scale, potentially risking saturation of the market and weakened demand and pricing power; and (2) situations where the buyer and acquisition target lack synergy, thereby, resulting in a different – and most likely, diminished – reputation in the eyes of consumers. (These are not necessarily mutual exclusive.)

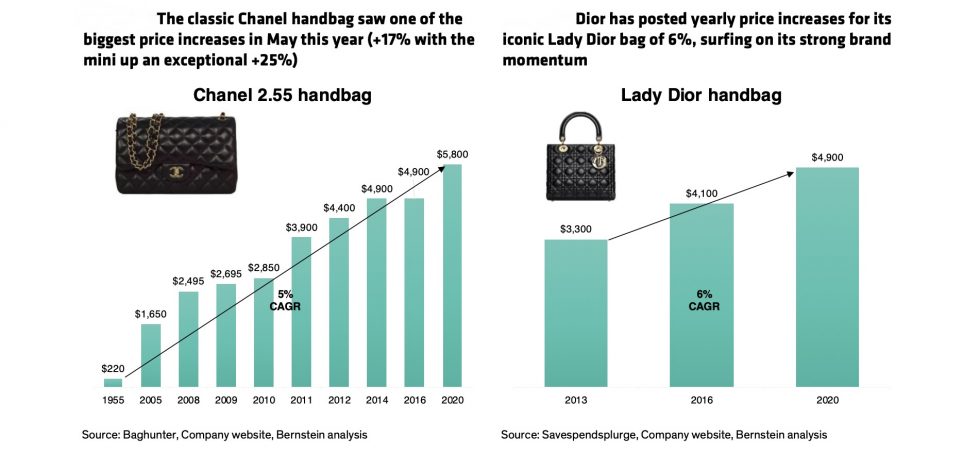

The first situation is a familiar one, as big fashion and luxury groups are in the business of buying up established but not-fully-scaled brands, and creating further opportunities for growth. There is a risk of over-saturation of the market as a whole – and the various regional markets – when volume is increased, which stands to negatively impact a carefully-positioned brand’s goodwill and equity, particularly if that positioning involves the notion of scarcity. However, luxury strategy consultant Jean-Noël Kapferer, for one, has long held that “the size of a brand and its growing volume of sales is not a problem, as long as prices keep rising.” And in the luxury sphere, prices are, in fact, rising – from Chanel and De Beers to Dior and Tiffany & Co.

Tiffany, which was brought under the LVMH umbrella late last year, is one example. Luxury consultant Alain Huy has predicted that within 5 years, LVMH is likely to double the size of Tiffany’s business, which generated revenues of $4.4 billion in fiscal 2019 and $2.2 billion through third quarter 2020. If such sales growth is to be achieved, it will require expansion both in terms of product and reach, and LVMH chairman and CEO Bernard Arnault says that the group is “optimistic about Tiffany’s ability to accelerate its growth,” presumably while still maintaining its cache. Or better yet, with Alexandre Arnault in place as the brand’s head product and communications, improving its cache, one splashy (and pricey) advertising exercise at a time.

Another example worth watching when it comes to maintaining brand equity while engaging in expansion is streetwear brand Supreme, which VF Corp. acquired in November 2020 for $2.1 billion. Given that Supreme has built a name that is “predicated on scarcity, which has driven the extremely strong full price sell-throughs and high margins,” Wells Fargo analyst Ike Boruchow has said that VF will need to “be careful about driving growth without losing the brand’s ‘secret sauce.’” Boruchow asserted that the biggest question in his mind centers on whether Supreme will be able to “balance growth and brand perception” amid VF’s plans for international expansion.

That is still up in the air, as major expansion efforts have not yet come into fruition. For the time being, the lines outside of Supreme’s New York locations each Thursday as of late – which is when the brand drops new wares, routinely drawing eager fans (and resellers) to its stores – seem to indicate that any potential for dilution has not kicked in. Any chance of waning demand will, of course, take time.

With the foregoing in mind, Tiffany and Supreme are key brands to watch if you want to gauge if – and how – companies can successfully balance the largely competing aims of equity and expansion.

The second scenario is one in which the buyer and acquisition target lack synergy, thereby, giving rise to a potential for a diminished reputation in the eyes of consumers. This very well might be what plays out in connection with the recent acquisition of Ralph & Russo. The London-based couture house made headlines early this month when it was bought out of bankruptcy for an undisclosed sum by Retail Ecommerce Ventures. In furtherance of what it calls a “strong track record of acquiring and growing iconic retail brands globally,” Miami-based REV has readily been snapping up bankrupt brands since it launched in 2019.

Unlike the allegedly mismanaged Ralph & Russo, whose clients consisted of British aristocrats, Hollywood stars, and Middle Eastern royalty, REV’s current holdings consist of mass market companies like Pier 1, Radio Shack, Stein Mart, and Dress Barn.

Speaking of 15-year-old Ralph & Russo, REV Executive Chairman Tai Lopez stated that it is a “globally celebrated brand with a unique position in the luxury sector and significant brand affinity.” The question is whether REV can maintain that position – and the goodwill associated with it – in a post-acquisition capacity. This is where synergy (or maybe better yet, a lack thereof) comes in. REV’s lack of experience in the high fashion space sets the companies up for a potential disconnect, which may only be furthered by the fact that Ralph & Russo founders Tamara Ralph and Michael Russo are no longer in the picture.

It is worth noting that goodwill does not automatically carry on just because it was once established by a company – i.e., if a brand does not continue operate in a way that enables it to hold a certain position and level of goodwill, it will lose it. As such, should REV operate Ralph & Russo in a way that consumers do not view is line with its previous endeavors (at least in a creative and client capacity), it runs the risk of losing value, which could have an impact on its pricing power. And if I had to guess, it is precisely the brand’s name and its association with truly high-end fashion that REV is likely banking on in order to leverage them to sell more accessible offerings in a purely digital capacity.

Again, it is too early to tell how it will play out, but I will certainly be watching.

Finally, it is worth considering – even with the foregoing in mind – that the notion of goodwill, while significant, is maybe not as rigid as we think it is. As marketing expert Mark Ritson asserted not too long ago, “The business of brand management is very risk-averse. We use words like ‘tarnish’ or ‘damage’ whenever we see a brand deviate from the strict trajectory that its positioning and brand image dictate.” But he also notes that “time after time, almost without exception, these deviations do not result in destruction.” Off-White and Virgil Abloh’s seemingly endless lineup of collaborations – from Evian and Ikea to Nike and Rimowa – something that goes against many of the tenets of high fashion and luxury marketing, might be proof of this. (There’s more about that here.)

The potential for brands to be surprisingly flexible in terms of their strength and for consumers to be forgiving in the face of robust expansion, if that expansion is done well, is something for companies to consider when it comes to the length to which they can extend their valuable brands, including in instances of buyouts.