Artificial intelligence (“AI”) tools are increasingly used at work to enhance productivity, improve decision making, and reduce costs, including automating administrative tasks and monitoring security. But sharing your workplace with AI poses unique challenges, including the question – can we trust the technology? Our new, 17-country study involving over 17,000 people reveals how much and in what ways we trust AI in the workplace, how we view the risks and benefits, and what is expected for AI to be trusted. We find that only one in two employees are willing to trust AI at work. Their attitude depends on their role, what country they live in, and what the AI is used for. However, people across the globe are nearly unanimous in their expectations of what needs to be in place for AI to be trusted.

AI is rapidly reshaping the way work is done and services are delivered, with all sectors of the global economy investing in artificial intelligence tools. Such tools can automate marketing activities, assist staff with various queries, or even monitor employees. To understand people’s trust and attitudes towards workplace AI, we surveyed over 17,000 people from 17 countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, the Netherlands, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States. This data, which used nationally representative samples, were collected just prior to the release of ChatGPT. The countries we surveyed are leaders in AI activity within their regions, as evidenced by their investment in AI and AI-specific employment.

Do employees trust AI at work?

We found nearly half of all employees (48 percent) are wary about trusting AI at work – for example by relying on AI decisions and recommendations or sharing information with AI tools so they can function.People have more faith in the ability of AI systems to produce reliable output and provide helpful services, than the safety, security and fairness of these systems, and the extent to which they uphold privacy rights.

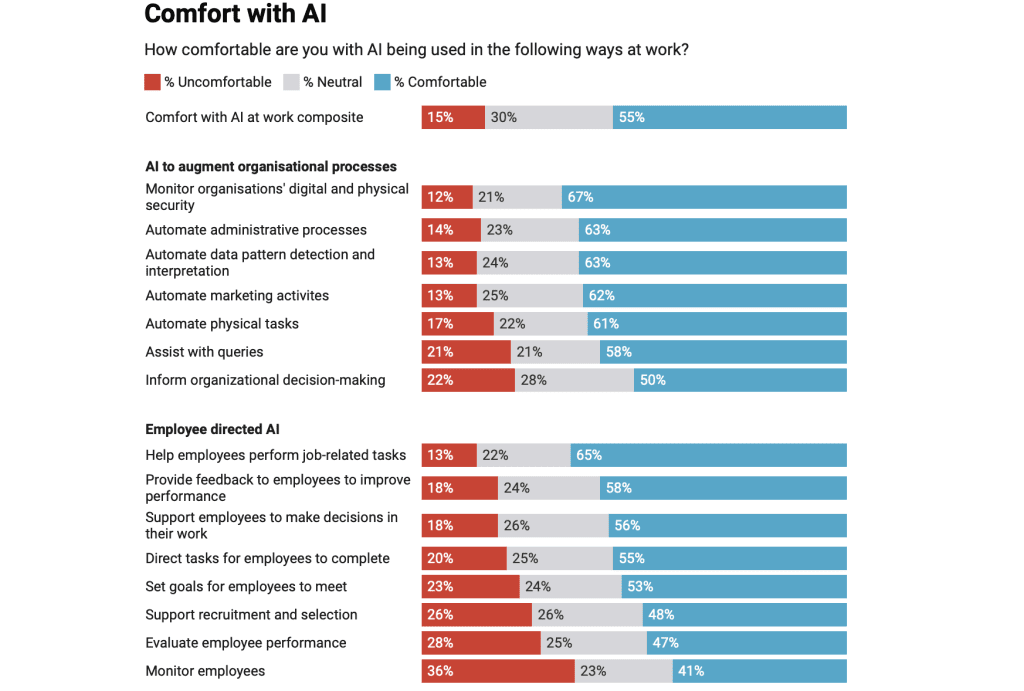

However, trust is contextual and depends on the AI’s purpose. As shown in the figure below, most people are comfortable with the use of AI at work to augment and automate tasks and help employees, but they are less comfortable when AI is used for human resources, performance management, or monitoring purposes.

AI as a decision-making tool

Most employees view AI use in managerial decision-making as acceptable, and actually prefer AI involvement to sole human decision-making. However, the preferred option is to have humans retain more control than the AI system, or at least the same amount. What might this look like? People showed the most support for a 75 percent human to 25 percent AI decision-making collaboration, or a 50 percent – 50 percent split. This indicates a clear preference for managers to use AI as a decision aid, and a lack of support for fully automated AI decision-making at work. These decisions could include whom to hire and whom to promote, or the way resources are allocated.

While nearly half of the people surveyed believe AI will enhance their competence and autonomy at work, less than one in three (29 percent) believe AI will create more jobs than it will eliminate. This reflects a prominent fear: 77 percent of people report feeling concerned about job loss, and 73 percent say they are concerned about losing important skills due to AI. However, managers are more likely to believe that AI will create jobs and are less concerned about its risks than other occupations. This reflects a broader trend of managers being more comfortable, trusting, and supportive of AI use at work than other employee groups. Given that managers are typically the drivers of AI adoption at work, these differing views may cause tensions in organizations implementing AI tools.

Younger generations and those with a university education are also more trusting and comfortable with AI, and more likely to use it in their work. Over time this may escalate divisions in employment. We found important differences among countries in our findings. For example, people in western countries are among the least trusting of AI use at work, whereas those in emerging economies (China, India, Brazil, and South Africa) are more trusting and comfortable. This difference partially reflects the fact a minority of people in western countries believe the benefits of AI outweigh the risks, in contrast to the large majority of people in emerging economies.

How do we make AI trustworthy?

The good news is our findings show people are united on the principles and practices they expect to be in place in order to trust AI. On average, 97 percent of people report that each of these are important for their trust in AI. People say they would trust AI more when oversight tools are in place, such as monitoring the AI for accuracy and reliability, AI “codes of conduct”, independent AI ethical review boards, and adherence to international AI standards.

This strong endorsement for the trustworthy AI principles and practices across all countries provides a blueprint for how organizations can design, use, and govern AI in a way that secures trust.

Nicole Gillespie is a Professor of Management and the KPMG Chair in Organizational Trust at The University of Queensland.

Caitlin Curtis is a Research fellow at The University of Queensland.

Javad Pool is a Research associate at The University of Queensland.

Steven Lockey is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at The University of Queensland. (This article was initially published by The Conversation.)