Golden Goose is pushing back against the trademark lawsuit that New Balance filed against it this summer for allegedly co-opting the design of its famed dad sneakers. On the heels of New Balance waging trade dress infringement and dilution claims against it in August, Golden Goose argues in a newly-filed motion that the plaintiff sneaker-maker’s complaint should be tossed out on the basis that it fails to plausibly allege that it owns a protectable trade dress in the hot-selling collection of 990 sneakers. In addition to failing to offer “a precise expression” of the alleged trade dress at issue, Golden Goose asserts that New Balance also falls short in alleging two foundational elements: that the alleged trade dress has acquired secondary meaning and that it is non-functional.

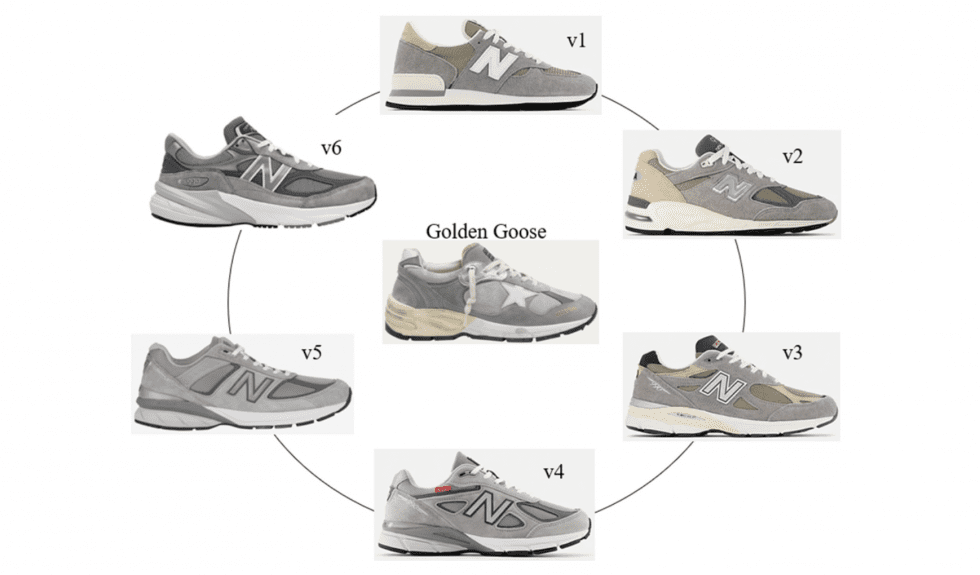

A bit of background: New Balance claims in the complaint that it filed with a federal court in Boston in August that “serial copyist” Golden Goose is on the hook for willfully infringing and diluting the common law trade dress that it has amassed in its 990 sneakers in order to “foster a perceived association between its products and New Balance in the minds of consumers” when no such association exists. Boston-based New Balance alleges that it has developed protectable rights in its line of 990 sneakers, including: “(i) Upper composed primarily of multiple tones of a single color (usually grey, blue, or black); (ii) Upper including mesh underlay with suede overlay creating mesh windows in forefoot and midfoot; (iii) Overlay bars in lateral and medial forefoot regions; (iv) Midsole having forefoot-to-midfoot portion of a first color (usually white) and different colored (usually grey) midfoot-to-heel portion; (v) Outsole of contrasting color (usually predominantly black); (vi) Reflective accents in upper; and (vii) Reinforced rear eyelets (usually two on both medial and lateral sides).”

According to New Balance, Golden Goose has run afoul of its trademark rights by way of its “Dad-Star” sneaker, which makes use of a design that mirrors the 990 trade dress. And “in addition to adopting a confusingly similar design” and style name, New Balance alleges that Golden Goose has gone so far as to “prominently use shades of grey in its infringing shoe model, which increases the likelihood of confusion, [as] New Balance and the 990 model are famously associated with the color grey.”

Golden Goose’s Motion to Dismiss

Against that background, Golden Goose – which is known for its $500-plus Italian handcrafted sneakers – asserts in a November 20 motion that New Balance’s claims should be dismissed as the plaintiff must: (1) identify the feature or features of its alleged trade dress with specificity; (2) sufficiently allege that such design features have acquired “secondary meaning” (i.e., that consumers recognize those features as source-identifying); and (3) allege that those same features are non-functional. The problem, per Golden Goose, is that New Balance “fails on all three of these.”

The 990 Trade Dress – Turning first to the alleged 990 sneaker trade dress, Golden Goose contends that New Balance “relies on a fiction that there is such a design as the 990.” While “there may be a line of shoes that New Balance sold under the 990 designation for the past forty years, New Balance itself admits that this particular model has been redesigned six times in forty years.” And “as the images provided in the complaint make clear, these re-designs have resulted in a 990 shoe that is not consistent in appearance or features.” To make matters worse, Golden Goose asserts that New Balance “does not explain in its complaint whether its purported trade dress rights extend to any single version of the 990 sneakers, all six of the versions, or to some combination thereof.”

In an attempt “to get around this deficiency in articulating its rights,” Golden Goose maintains that New Balance “resorts to stating that four of the seven claimed features of its trade dress are ‘usually’ present.” However, Golden Goose argues that “no party may obtain a monopoly over a product design by stating that it is ‘usually’ presented in one way or another, that [New Balance] owns six different variations of its alleged design, and that the exclusive design rights continue years after some of these shoes have been phased out completely from the marketplace.” In short: “New Balance is overreaching,” Golden Goose insists.

Secondary Meaning – With regard to secondary meaning, Golden Goose states that New Balance’s complaint is “riddled with the same generalized allegations.” Instead of “tying its allegations to any particular trade dress or features,” New Balance opts to “focus on the success of the New Balance brand itself and its 990 line of shoes; but, again, we do not know which version or versions of the 990 design the allegations pertain to, and New Balance does not allege that it engages in any ‘look for’ advertising related to any of the particular features of the claimed trade dress – or even that it advertises and promotes the trade dress as opposed to the product itself.”

More than that, New Balance does not allege that it performed a consumer survey showing that the design has “achieved independent consumer recognition as a New Balance product,” according to Golden Goose.

(A note on surveys: While not necessary, consumer surveys are an important way to demonstrate secondary meaning in trademark and trade dress cases. As Judge N.D. Ill. Judge Robert W. Gettleman, for one, held a few years ago in an unrelated trademark case, “a lack of a consumer survey is not per se fatal … but in its absence, the other [secondary meaning] factors must strongly support a claim for secondary meaning.” In a separate trademark case around the same time (Root Causes Medicine, LLC v. Petersen), a federal judge in Texas stated that the defendants’ failure to cite consumer survey evidence “weighs heavily in the plaintiffs’ favor.” And more recently, in a trade dress case centering on a Connect 4 game, the U.S. Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit found that intentional copying and survey evidence were sufficient to create a triable issue of fact about secondary meaning, marking yet another nod to the importance of surveys in establishing secondary meaning.)

Non-functionality – Finally, Golden Goose asserts that while New Balance must allege sufficient facts to overcome the “statutory presumption that features are deemed functional until proved otherwise,” it fails to do so. Reflecting on the functionality of the 990 features, “New Balance makes only bare, conclusory assertions of non-functionality,” per Golden Goose, which further argues that “many of the claimed features of the 990 design were or are protected by utility patents, and it is black letter law that New Balance cannot obtain protection through trade dress of functional features for which New Balance has already obtained utility patent protection.”

For instance, Golden Goose states that New Balance alleges that its trade dress includes, in part, the “upper including mesh underlay,” “reflective accents,” and “reinforced rear eyelets” – all of which are features that New Balance identified as functional in its utility patents.

With the foregoing in mind, Golden Goose urges the court to toss out New Balance’s trademark-centric complaint in its entirety, including the plaintiff’s state law claims, which are “infect[ed]” by the very same issues as the Lanham Act causes of action.

The case is New Balance Athletics, Inc. v. Golden Goose USA, Inc., 1:23-cv-11898 (D.Mass.).