Chanel and What Goes Round Comes Around are preparing to go to trial in the trademark case that Chanel filed against the luxury resale company more than five years ago. In its March 2018 complaint, Chanel accused What Goes Around Comes Around of attempting to “deceive consumers into falsely believing [that it] has some kind of … affiliation with Chanel or that Chanel has authenticated [its] goods in order to trade off of Chanel’s brand and goodwill.” In addition to offering up allegedly infringing Chanel-branded handbags and point of sale products, Chanel has accused WGACA of improperly using its trademarks in ad ad campaigns and social media marketing. In response, What Goes Around Comes Around argued that it should be shielded from liability on the basis that Chanel’s lawsuit is an impermissible attempt by the brand to bar the legitimate resale of Chanel products, and that it uses the Chanel trademarks simply to identify its products (which it claims amounts to nominative fair use), and does not claim any affiliation or sponsorship by Chanel.

Following a partial summary judgment grant for both parties in March 2022 and in the wake on more than one discovery clash, the case is slated for trial this fall, and a number of new filings, as first reported by TFL, shed light on what can be expected, namely, in terms of a couple of the experts’ testimonies. In new declarations submitted by Chanel, the luxury brand’s expert witnesses give a sneak peek at consumer surveys that were carried out to gauge consumer confusion in connection with What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”)’s sale of Chanel products. At the same time, Chanel’s damages expert provided figures for what the brand will claim that it is entitled to in terms of monetary damages.

Consumer Surveys

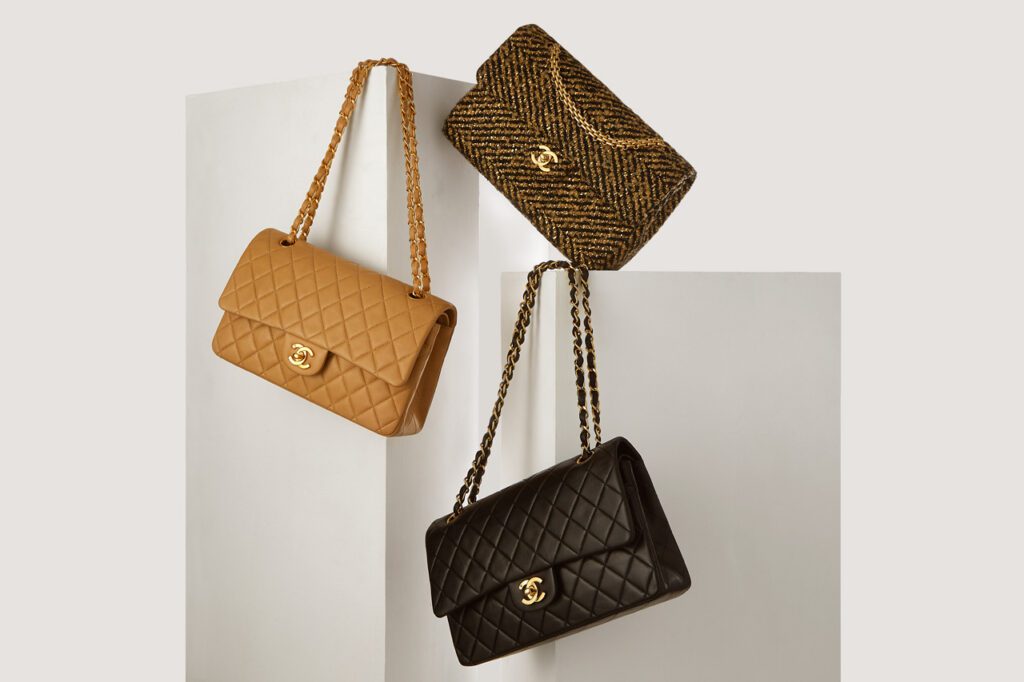

First things first, trademark law professor and McCarthy Institute for Intellectual Property Law director David Franklyn states in a declaration that he will testify at trial about two surveys that he designed and carried out to test the extent to which WGACA’s presentation of CHANEL-branded items creates a likelihood of confusion. Franklyn’s first survey was used to evaluate consumer perceptions of WGACA’s website, and in particular, their perceptions of several statements. After being shown various images of CHANEL-branded items offered for sale by WGACA in 2015 and the “About Us” page that appeared on the WGACA website in 2015, consumers were asked about whether: (1) a certain handbag was previously sold by Chanel or an authorized retailer; (2) Chanel had authorized WGACA to guarantee authenticity; (3) a specific handbag had been refurbished, re-dyed, or repaired; (4) a handbag had passed Chanel’s internal quality control standards; (5) a certain handbag was vintage; and (6) a necklace had been repaired.

Additionally, consumers were asked about their perceptions regarding the relationship between Chanel and WGACA, “specifically whether Chanel had approved (or not approved) or sponsored (or not sponsored) the sale of a handbag on the WGACA website, as well as whether there was any association between Chanel and WGACA.” From this, Franklyn says he observed that …

– A significant percentage of consumers incorrectly perceive WGACA as an authorized reseller of Chanel, or that WGACA is an affiliate, partner, or collaborator of Chanel.

– The majority of consumers within this interested universe are confused as to the relationship between Chanel and WGACA, believing that Chanel sponsors or, approves WGACA’s activities, or has an association with WGACA.

– A significant percentage of consumers in this interested universe were left with false impressions regarding the Chanel-branded products offered on the WGACA website.

– The majority of consumers within this interested universe show declined interest in purchasing Chanel-branded products from the WGACA website after being made aware of facts regarding certain Chanel-branded products sold on the website.

As for his second survey, Franklyn used that to “evaluate the level of confusion as to source, as well as sponsorship, approval, or association with another company or companies.” Here, one half of the consumer participants were shown an image of a WGACA pop-up shop within a Von Maur department store, in which it offered up Chanel-branded products for sale; for the other half, the image was digitally altered to remove the interlinked “CC” logo from the handbags presented within the image. Based this survey, Franklyn asserts that “a significant percentage of consumers … were confused as to the source for the pop-up shop,” believing that the luxury brand was the source rather than WGACA.

Overall, Franklyn intends to testify that WGACA’s presentation, both online and in physical stores, “has created the impression of a relationship with Chanel and given consumers a false impression of the Chanel-branded products sold on WGACA’s website.” Specifically, after reviewing the WGACA website, “a significant percentage of consumers [said that they] believe that the two brands have a relationship,” with two out of every three surveyed consumers (67 percent) saying that they believe that Chanel “approves, sponsors, or is associated with, WGACA,” per Franklyn. “Moreover, after reviewing the WGACA website, a significant percentage of consumers are left with the impression that Chanel has authorized WGACA to guarantee authenticity, that Chanel products have previously been sold by Chanel or an authorized seller, that products have not been refurbished or repaired, that products sold are vintage, and that products have passed Chanel’s internal quality control standards.”

TDLR: “At trial I will testify that WGACA’s presentation of Chanel goods both online and in physical retail sales poses a serious threat to the famous CHANEL trademarks, goodwill, and brand equity which Chanel has spent the last 120 years building,” Franklyn states in his declaration.

Damages to Chanel

In a declaration of his own, Andrew Safir, who is the president of Recon Research Corporation, an economic advisory firm specializing in the analysis of asset valuation, financial performance, and corporate damage calculation, reveals that he will offer expert opinions and testimony regarding the damages due to Chanel from WGACA based on the financial information WGACA has produced in this case, which covers the period of 2014 through May 2022.

In sum, Safir says in the declaration that it is his opinion that Chanel has suffered damages of $23.2 million as a result of WGACA’s acts of trademark infringement, false association, and false advertising, a sum that is approximately 70 percent of the net profits earned by WGACA as the result of the sale of Chanel branded products.

The case is Chanel, Inc. v. What Goes Around Comes Around, LLC, et al., 1:18-cv-02253 (SDNY).