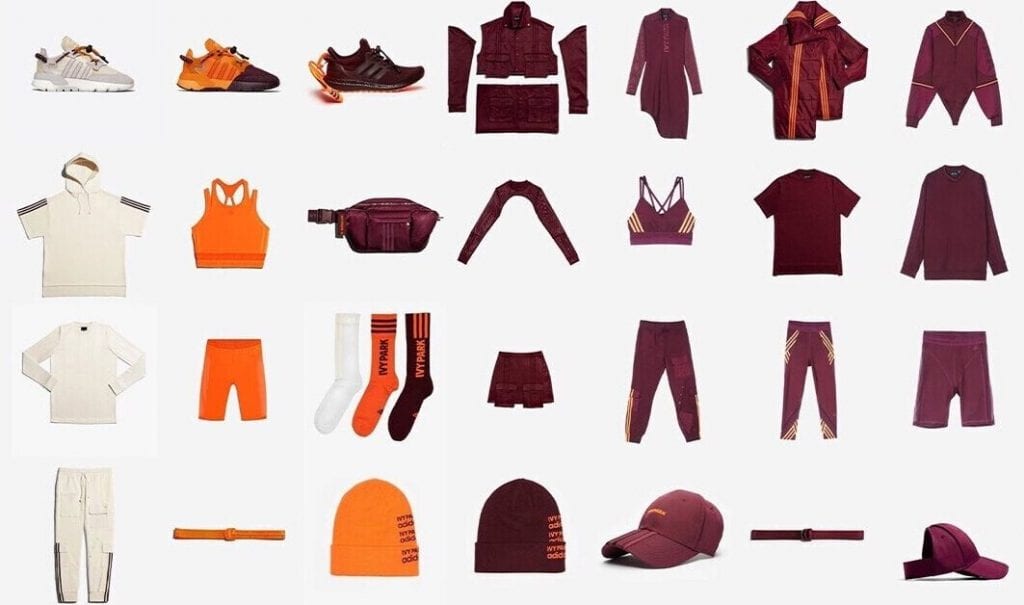

By way of an expansive collection of limited-edition and gender-neutral jumpsuits, track jackets, tunics, sports bra, biker shorts, and sneakers, among other things, Beyoncé made her highly-anticipated debut with adidas in January. The new collection marks the first time that the Grammy winner has held full control of her Ivy Park line, which she launched in 2016 as a joint venture with Topshop owner Sir Philip Green; she has since bought of Green. It also marks an opportunity for adidas to boost sales in the critical North American market.

Thanks to the color palette of the Beyoncé x adidas wares, the collection quickly drew comparisons – from social media users – to another brand, albeit not a fashion one. “When Beyoncé’s collection came out, we saw lots of people organically say it kind of looked like [ours],” Popeyes’ Chief Marketing Officer Fernando Machado told the Wall Street Journal this week. As it turns out, the maroon and orange hues of the Ivy Park athletic pants, biker shorts, hoodies, etc. made the collection a dead ringer, for some, for the uniforms that employees at the fast food chain wear.

The comparisons were not lost on a seemingly very savvy Popeyes. The New Orleans-founded, Miami-based chain’s marketing team – and Miami-based advertising agency GUT, which Popeyes enlisted last year “during the craze over its new chicken sandwich,” according to the WSJ – stepped in with what the Los Angeles Times has called “a genius effort to leverage the buzz.” That effort? A new collection of uniforms inspired by the Beyoncé and adidas wares. Popeyes even released a lookbook to coincide with the collection – coined “That Look From Popeyes” – which mirrored the one that the music mega-star and the brand known for its three-stripes recently rolled out.

The internet went wild; the Popeyes collection, which was made available to the public, sold out in a day with all proceeds from sales of the clothing going to charity, the chain says; and the media had a field day about the whole thing, of course.

With the dust settling from the initial PR blitz and as Popeyes scrambles to restock its collection, questions have arisen about the viral marketing stunt and about the Ivy Park collection, alike. The Los Angeles Times’ Adam Tschorn, for instance, recently pondered, “Did the Ivy Park design team intentionally take inspiration from or pay homage to the chicken joint?,” while menswear site Complex, asked, “Can Beyoncé or Adidas Sue Popeyes Over Its Ivy Park-Inspired Collection?” (Easy answer: No!).

What might be the more interesting angle, however, is one that centers on the power of branding and the role that color plays in that endeavor. After all, the use of two colors – a striking orange hue paired with a deep maroon – alone, was enough to get a sizable pool of consumers (in the U.S., at least) to think of a single source … Popeyes, when the Ivy Park collection made its debut. That is not something to be taken lightly. After all, consumers actively linking something like a color to a single source is precisely what gives rise to the ability of that source (i.e., company or brand) to claim rights in it.

To date, Popeyes has not filed trademark applications for registration for its maroon and orange combo (not that it needs to, as in the U.S., trademark rights are generally amassed by using the mark and not simply filing an application for one). But just because Popeyes has not embarked on a quest to gain formal rights in its colors by way of a trademark registration does not mean that others have not done so for their respective brands.

In fact, the crusade for colors is increasingly well-chartered territory. Christian Louboutin, for instance, first made headlines in 2012 in connection with the lawsuit that it filed against Yves Saint Laurent for allegedly infringing its trademark rights in the use of a specific color red on shoe soles. That lawsuit prompted headlines and interesting (and difficult) questions about the role of color – and the potential monopolization of color – in creative industries like fashion.

Tiffany & Co. famously maintains exclusive rights in its “robin’s egg blue” for use on an array of goods and services, ranging from fragrance products, tableware, and leather goods to product packaging and retail services … and of course, jewelry. The color, itself, Tiffany’s rights in it, and the goodwill associated with it in the minds of consumers is a sizable part of what prompted the LVMH acquisition, Reuters recently revealed. “LVMH’s billionaire boss Bernard Arnault, a renowned dealmaker … was [focused on] getting control of Tiffany’s most valuable assets: all the [protected] elements that came with the Tiffany brand, notably its robin’s egg blue boxes,” the publication reported in November.

Still yet, Hermes has rights in its orange of choice, Cadbury had its specific shade of purple, UPS has a Pantone shade of “Pullman” brown, T-Mobile has its magenta, and the list goes on.

These companies’ trademark rights in specific shades for use on specific classesof goods and/or services in specific geographic regions (trademark rights are not blanket global assets and vary by jurisdiction) is contingent upon their ability to show – by way of a handful of factors, such as unsolicited media attention, advertising expenditures, sales success, market surveys, etc. – that their use of the color has acquired distinctiveness. In other words: consumers have reason to link that specific use of a specific color to a single source, and actually do associate the color with a single source.

As for the claiming of rights in two colors used in conjunction, that is not unheard of either. In a non-fashion example, John Deere maintains an array of registrations for its use of the colors yellow and green on agricultural equipment, which at least one dating back to 1988. As recently as 2017, the tractor-making giant filed a trademark infringement suit against another agriculture-centric company for using the colors on its products, and in siding with John Deere on its infringement and dilution claims, the court – a federal court in Kentucky – also inherently upheld the validity of Deere’s dual color trademarks.

As for whether Popeyes plans to take legal action over Ivy Park’s use of “its” colors, it seems unlikely; the company seems perfectly happy to engage in a bit of viral back-and-forth with Beyoncé and adidas, a move that not only speaks to its marketing prowess but that highlights the power of its visual identity as a brand, something that the consumer comparisons and media attention in connection with the Ivy Park collection seems to only bolster even further.

Ultimately, the rising reliance by companies on color as an integral part of their brand makes sense, as in much the same way as a brand name or logo acts as an immediate indicator of the source of a product or service for consumers, color can play an important source-identifying function, as was made perfectly clear on social media when users began linking Ivy Park’s maroon and orange color scheme to Popeyes. With all of this in mind, it should come as little surprise that just as many brands have been able to bank on the recognizability and appeal of their more traditional trademarks, no shortage are looking to color for the very same benefits.