Last year, New York became one of the first states in the U.S. to pass a right to repair law, with the state senate green-lighting the Digital Fair Repair Act in June, and New York Governor Kathy Hochul signing the bill on December 28. Slated to go into effect on July 1, 2023, the Act requires original equipment manufacturers (“OEMs”) to make tools, parts, and diagnostic and repair information available to owners of digital electronic equipment, as well as to independent repair providers. While the strength of the law is being debated (the bill was “meaningfully compromised at the last minute by amendments that give OEMs some convenient exceptions and loopholes to get out of obligations,” the Verge reported recently), the Act is noteworthy, nonetheless, as it comes amid growing momentum for broader repair rights.

“Other states are weighing right-to-repair bills, and both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives have introduced right-to-repair bills known as the Fair Repair Act,” Sidley Austin’s Marissa Alter-Nelson, Ernesto Claeyssen, and Amy Lally noted this summer. At the same time, in the wake of a 2021 competition-focused Executive Order in which President Biden highlighted the importance of making it “easier and cheaper” for consumers to “repair items [they] own by limiting manufacturers from barring self-repairs or third-party repairs of their products,” the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) made good on its vow to crack down on “illegal repair restrictions.”

The FTC announced in October that it had approved final orders in cases against Harley Davidson, Weber-Stephen Products, and MWE Investments, accusing the companies of including terms in their warranties that stated that product warranties would be void if customers used independent repairers or third-party parts, in violation of the “anti-tying” provision of the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act (“Warranty Act”) and the FTC Act.

In connection with the settlements, the FTC revealed that the orders against Weber, Harley-Davidson, and MWE Investments, which owns outdoor generator-maker Westinghouse, make it clear that companies cannot condition product warranties on a consumer’s use of a branded article or a service (other than an article or a service provided without charge), unless the warrantor applies for and receives a waiver from the FTC. As part of the settlements, the companies were also required to revise their warranties by adding language that conveys to consumers: “Taking your product to be serviced by a repair shop that is not affiliated with or an authorized dealer of [Company] will not void this warranty. Also, using third-party parts will not void this warranty.”

More than Just Motorcycles

To date, the FTC’s efforts have focused on goods like motorcycles, grills, and generators, but that does not mean that other market segments, such as luxury, are entirely unaffected by the increased emphasis on the right to repair. “There have been prominent examples of manufacturers” – across industries – “selling expensive products and refusing to allow independent repairs on them,” Wallace Witkowski previously wrote for MarketWatch, noting that one of the most cited examples is John Deere & Co. because farmers sued the farm-equipment maker for access to the software that ran their tractors so they could repair the equipment.”

But the issue is widespread: “Every industry has its Apples and its John Deeres,” he says. This is particularly true as manufacturers across industries have “increasingly designed products to make them difficult to repair without specialized equipment and instructions,” and beyond that, have strictly limited the parties that are “authorized” to conduct repairs without compromising the validity of a product’s warranty.

Looking beyond the likes of Harley Davidson, Weber, and co., which came under fire for stringent warranties that were heavily reliant on repairs being performed only with their brand-name parts and by authorized parties, luxury timepieces come to mind as potential targets of regulatory attention. In fact, in a report in May 2021, entitled, “Nixing the Fix: An FTC Report to Congress on Repair Restrictions,” the FTC noted that in response to a call for public comment on the issue of repairs, it received information claiming that “certain warrantors either expressly or by implication continue to condition warranty coverage on the use of particular products or services.”

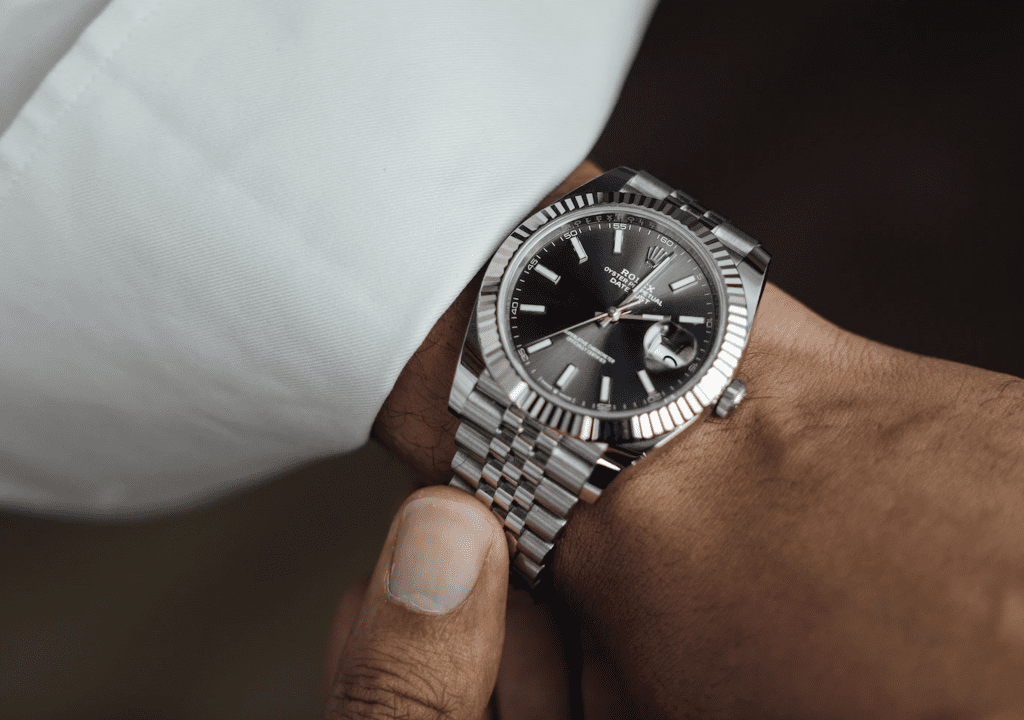

Among the companies cited by commentors? Rolex. At least one commenter told the FTC that the Swiss watchmaker’s “materials make statements such as, ‘only official Rolex repair centers are ‘allowed’ to repair and service a Rolex watch’ and that repair work done by anyone other than a Rolex facility will void its warranty.’” (As of the time of publication, the terms of Rolex’s website included language that states that “any addition or substitution of parts or accessories with those not manufactured by Rolex, as well as any alteration, modification or other material change made to or on Rolex products by a third party not authorized by Rolex cancels the warranty. Rolex does not approve any modification made by non-authorized third parties on the Rolex products … as well as any customization activity. These modifications may harm the quality and the integrity of the Rolex products.”)

Rolex is, of course, not the only luxury watchmaker that takes such a stance on parts and/or services, a position that could be problematic from an anti-tying perspective because, as the FTC has held, “Companies cannot tell customers they will void a warranty or deny warranty coverage if the customer uses a part made by someone else or has someone other than the dealer repair the product.”

There are exceptions to the rule here, including when a “company has received a waiver in advance from the FTC after proving that the product will work properly only if a specific branded part is used” and that such a waiver is in the interest of the public. But the FTC and other experts seem skeptical about the broad applicability of such waivers. Generally speaking, the FTC has said that in many cases, there is “scant evidence to support manufacturers’ justifications for [such] repair restrictions.” Specifically, the regulator determined that these exceptions did not apply in the cases involving Harley Davidson, Weber, and MWE. In the complaint that it lodged against Weber, for instance, the FTC asserted that “for some of its gas and electric grills,” the Illinois-based company included a provision in its user manual and warranty that stated, “The use and/or installation of parts on your WEBER products that are not genuine WEBER parts will void this warranty.” Because Weber did not get a waiver and did not provide those parts and labor for free except in the case of defects, the FTC argued that “the two narrow exceptions do not apply.” Therefore, the FTC argued that Weber’s policy that using non-Weber parts will void consumers’ warranties violates the Warranty Act.

In addition, the regulator claimed that “by conditioning the validity of the warranty on the use of Weber parts that were not provided free to the consumer, Weber engaged in an unfair or deceptive practice, in violation of the FTC Act.”

As for watches, in particular, Joshua Sarnoff, a professor of law at DePaul University, is not convinced that watchmakers would be on strong footing if they were to seek such waivers. “I have little doubt that someone could make repair parts for a watch,” and although, luxury watch parts may be of higher quality, he says that quality is “not the question” at issue when it comes to the Warranty Act waiver. The critical element in the eyes of the law is whether the product “will function properly” as a result of a third-party service or with third-party repair parts.

This, of course, raises questions about the seemingly prevalent practice of conditioning the authenticity of a luxury watch – and thus, the validity of its warranty – on that product being serviced and/or repaired exclusively by the brand or an authorized brand dealer/service provider. And it particularly relevant as companies across the luxury segment increasingly look to warranties and repair services at least in part to cushion the shock of consistently rising price tags.

Looking Ahead

In addition to the passage of the Digital Fair Repair Act in New York, which is expected to have implications beyond just the boundaries of the state, repair-focused remarks from FTC chairwoman Lina Kahn as recently as this fall suggest that right to repair will remain a relevant issue, and the FTC, in particular, will “continue to view combating allegedly unlawful repair restrictions as a priority and that the regulator’s enforcement efforts in this arena are not likely to abate anytime soon,” Sheppard Mullin’s John Carroll and Joseph Antel asserted in a note. As the FTC’s enforcement actions – including those against Harley Davidson, Weber, and co. – illustrate, the regulator “may target fairly commonplace warranty practices intended to promote consumer safety and limit liability and reputational harm to companies and their brands.”

Parties that have such policies in place “should be prepared for scrutiny from the FTC as well as, potentially, private plaintiffs,” they assert.

Companies should also be prepared for additional issues. The Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act is clearly the FTC’s “key tool at the moment” in terms of regulating repairs, Baker & Hostetler’s Daniel Kaufman wrote this summer. It is worth noting that the Act addresses “one fairly narrow aspect of broader right-to-repair issues – how warranties relate to repairs, but there are many other right-to-repair issues – such as product designs that may complicate repair, lack of access to parts, and repair information and designs that may make independent repairs less safe – that go beyond the scope of that Act.”

“It remains to be seen whether the FTC will start to look at repair issues with a broader range of tools,” per Kaufman. Either way, he contends that “if you sell a consumer product with a warranty, it is a good time to take a fresh look at the terms of the warranty to make sure you stay out of the FTC crosshairs.”