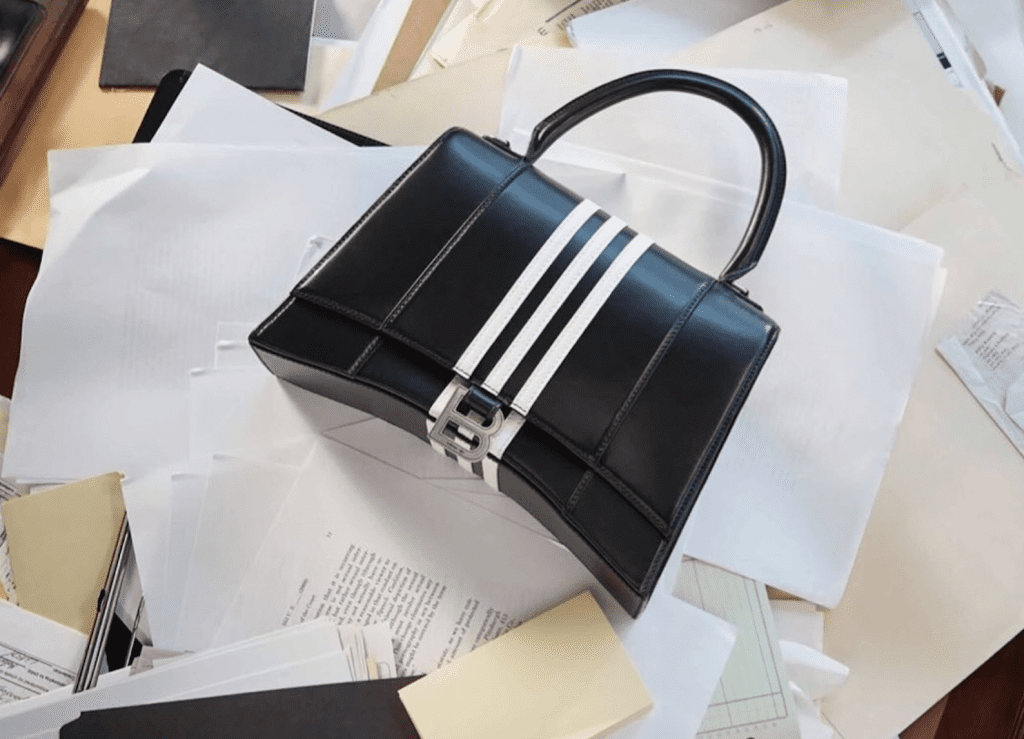

Ahead of the close of the year, Balenciaga has landed to the receiving end of a public relations crisis thanks to its release of two ad campaigns, one that depicted young children holding plush bear bags in S&M-style harnesses, and another – the Garde-Robe campaign – that included a page from the Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. v. Williams, a case that focused on a child pornography statute. Faced with mounting controversy over the campaigns, Balenciaga pulled the ad campaigns from its website and issued two successive apologies last month. When those attempts only stoked further ire among consumers, the brand filed a lawsuit, naming production company North Six, Inc. and its agent, Nicholas Des Jardins, the latter of whom designed the set for the Garde-Robe campaign, as defendants.

In a summons and notice lodged with a New York state court on November 25, Balenciaga alleged that the defendants engaged in “inexplicable acts and omissions” that were “malevolent or, at the very least, extraordinarily reckless.” Again, the move was met with consumer fury. The general consensus: Balenciaga was looking to shift the blame. The contract-centric case was short-lived. In a statement on December 2, Balenciaga CEO Cédric Charbit announced that the company would no longer pursue the litigation, and in a filing on the same day, the Kering-owned company alerted the court that it would “voluntarily discontinue” the action.

A Crash Course

The lawsuit was over before it even really started, but the entire matter is the latest example of how companies are handling – or should handle – high-profile crises. Reflecting on the controversy, public relations professionals and legal experts, alike, claim that Balenciaga would have fared more favorably had it taken more responsibility from the outset and not tried to blame others, including by way of a lawsuit that it was unlikely to win, especially in the court of public opinion.

Companies responding to a crisis generally should “not seek to blame others or try to avoid responsibility,” DWF LLP attorney Mark Thompson stated in a note. While blame-shifting is not an untested response to consumer-facing crisis (in fact, the Institute for Public Relations lists the “Scapegoat” approach as one reputation repair strategy), as the Balenciaga situation demonstrates, this approach is not always appropriate, particularly as “anything a brand puts out into the public domain is owned by that brand,” according to Megan Matthews, a brand and PR strategist at Instinct Brand Equity.

“When a brand makes a mistake, ownership of the mistake with a clear outline for what is being done about it, or how to prevent it in the future is the next step,” says Matthews. “By blaming ‘the parties responsible for creating the set,’ Balenciaga [was] shifting blame from the brand leaders to the teams involved, but at the end of the day, the brand (and ultimately, its leadership) signed off on the campaign.” And consumers were quick to note that, as well, with many expressing skepticism that an established brand like Balenciaga was not heavily involved in creating – and ultimately, approving – the controversial ad campaigns.

In addition to taking responsibility for their part in a crisis, companies are also often encouraged to act promptly. “You need the leadership, the structure and the tools” to handle a PR crisis, lawyer and communications consultant James Haggerty writes, and “you need them ready to go at the speed of the modern crisis.” Speed should not come at the expense of proper messaging; the rationale here is that if a company responds quickly, it can communicate its side of the story/shape the narrative, and ideally, minimize the spread of inaccurate information and/or conspiracy theories that could lead to more damage. (Not devoid of speculative theories, social media users linked the Balenciaga ads to a pedophile-centric conspiracy theory from far-right-wing group, QAnon.)

Beyond that, a swift response may also help to circumvent an unnecessarily protracted controversy.

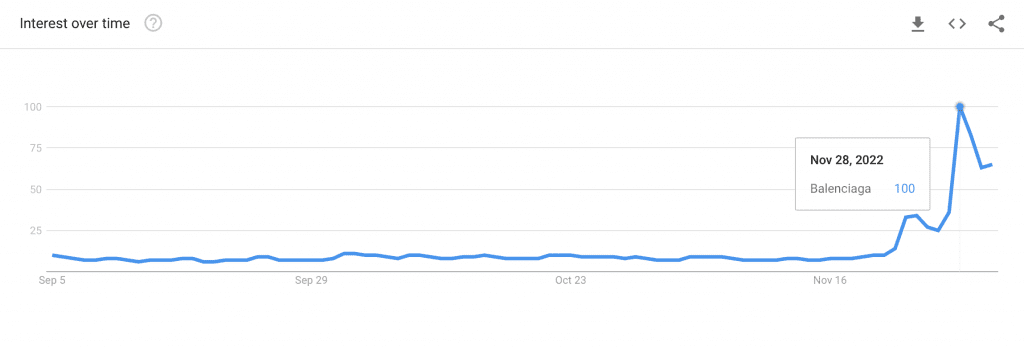

Balenciaga appears to have fallen short here. By escalating its deflection strategy with a lawsuit over the Garde-Robe ad campaign, and failing to release accountability-centric statements from key leaders in what consumers deemed to be a timely manner, Balenciaga heightened and prolonged the situation. The lawsuit amplified the situation further, giving rise to the Streisand Effect. Readership of articles about the situation rose in the wake of the lawsuit’s filing, according to Axios. And Google search trends show that searches for “Balenciaga” spiked on November 28, the day that major outlets like Washington Post, the New York Times, Bloomberg, etc. published articles about the lawsuit.

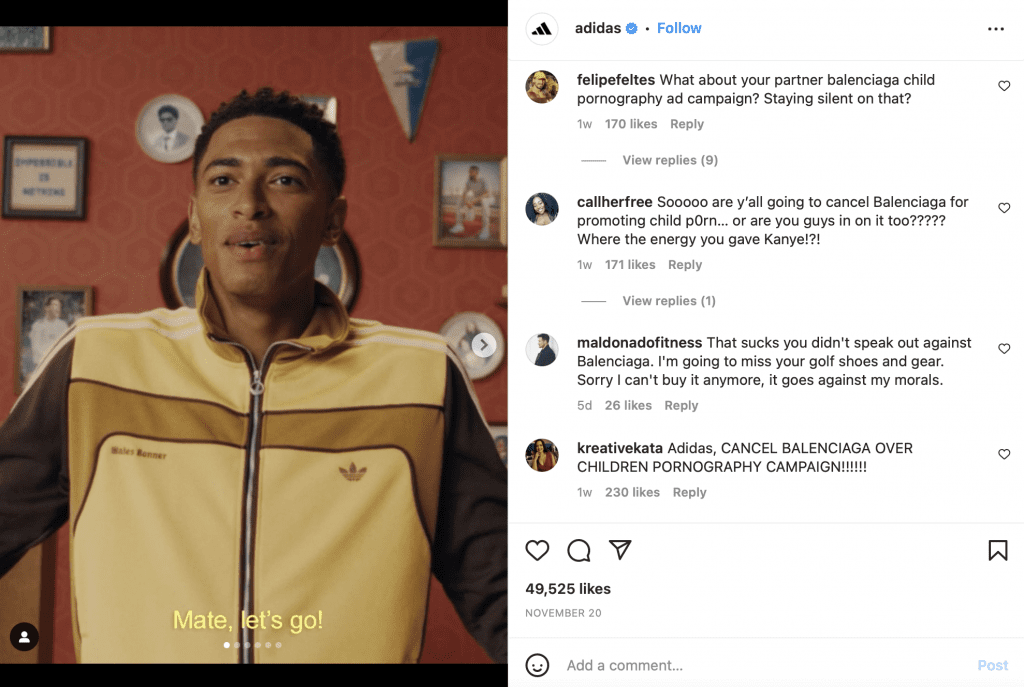

At the same time, the perceived lag between Balenciaga pulling the ad campaigns and the brand’s leadership taking full responsibility for the “grievous errors” and “lack of oversight,” and clearly mapping out the path forward angered consumers. In addition to publicly demanding that Balenciaga take action, consumers also bombarded – and continue to bombard – some of its partners, like adidas, and famous endorsers, including Kim Kardashian, over their connections to the brand.

The Balenciaga situation – paired with consumers’ unhappiness with adidas’ unwillingness to quickly sever ties with collaborator Kanye West after multiple instances of antisemitism and other hate speech – seem to clearly indicate that while companies and their counsel may want to take a “wait and see,” or at least, a wait until all essential information is collected, plan of attack, they may be punished if consumers perceive a lack of appropriate action.

Continued Controversies

Balenciaga’s PR predicament is not the first of its kind in fashion or beyond. Haggerty points to an array of “big-name” crises that have unfolded in recent years, including the BP oil spill, the Target data breach, the Volkswagen emissions scandal, Fox News’ sexual harassment scandal, and United Airlines forcibly removing a passenger from an overbooked flight. Dolce & Gabbana’s alienation of Chinese consumers as a result of a racist ad campaign in 2018 also comes to mind. “The one thing that really binds [these situations] together,” he contends, “is the fact that the initial response was fumbled, and it was days or weeks before the company could get its act together.”

Given that such crises have played out very publicly in the past, enabling companies, their PR teams, and their legal counsels to bear witness, one of the questions worth pondering is: Why do companies’ responses to largescale controversies continue to make matters worse?

There are a few reasons, according to Haggerty, but “the biggest is the fact that companies just aren’t ready. They haven’t gamed out the scenarios beforehand. And there is a natural human tendency to want to ignore problems in the hope they go away.” In some cases, he claims that “companies and their advisors act like there is no way they could have predicted a particular crisis.” Haggerty disagrees. A passenger incident is something United Airlines “should be able to anticipate, just like a data breach at Target or an oil spill by a company that drills in the Gulf of Mexico,” he states. These are the types of things that companies can – and should – anticipate as a matter of risk management.

“Having a plan in place ahead of time in order to get in front of a situation rather than simply reacting to whatever transpires is critical,” Fisher Phillips attorney Andria Ryan states, particularly given that “everyone now has the ability to broadcast anything to the entire world” thanks to smart phones and social media platforms. That planning and preparation allows companies to react faster and make more effective decisions.

As for how prepared Balenciaga could have reasonably been in order to avoid its initial, ineffective response, there is an argument to be made that the brand should have known that at some point, either it – or any of its key figures or collaborators – could have offended consumers. Not only is Balenciaga readily looking to push the envelope in terms of its offerings, but other brands and individuals – from Prada, Dolce & Gabbana, and fellow Kering-owned company Gucci to John Galliano and Kanye – have faced significant backlash in the past for products and/or communications that were deemed to be unacceptable. There has been enough controversy in the relatively recent past for fashion companies and creatives to assume that it is not impossible that they could similarly face far-reaching backlash.

In terms of what this means going forward, Balenciaga says that it is implementing “new control instances” and organizational practices, including a reorganization of its image department to “ensure full alignment with our corporate guidelines.” More broadly, as big brands continue to onboard high-level figures – from chief diversity officers and chief privacy officers to heads of their metaverse endeavors – it might mean a new role is in the making: Chief Crisis Officer. For smaller entities, this probably means that in-house and outside counsels will be called on to take bigger roles in helping to prevent, prepare for, and address crises.

This trend was already underway, with lawyers “finding themselves thrust into a crisis communications role, either as the Chief Crisis Officer or working with business executives and public relations pros as part of the crisis communications team,” Haggerty says. But the onset and immediate aftermath of the Balenciaga scandal is rumbling through fashion industry companies and forcing them to consider just how prepared they are … or are not for issues of their own.