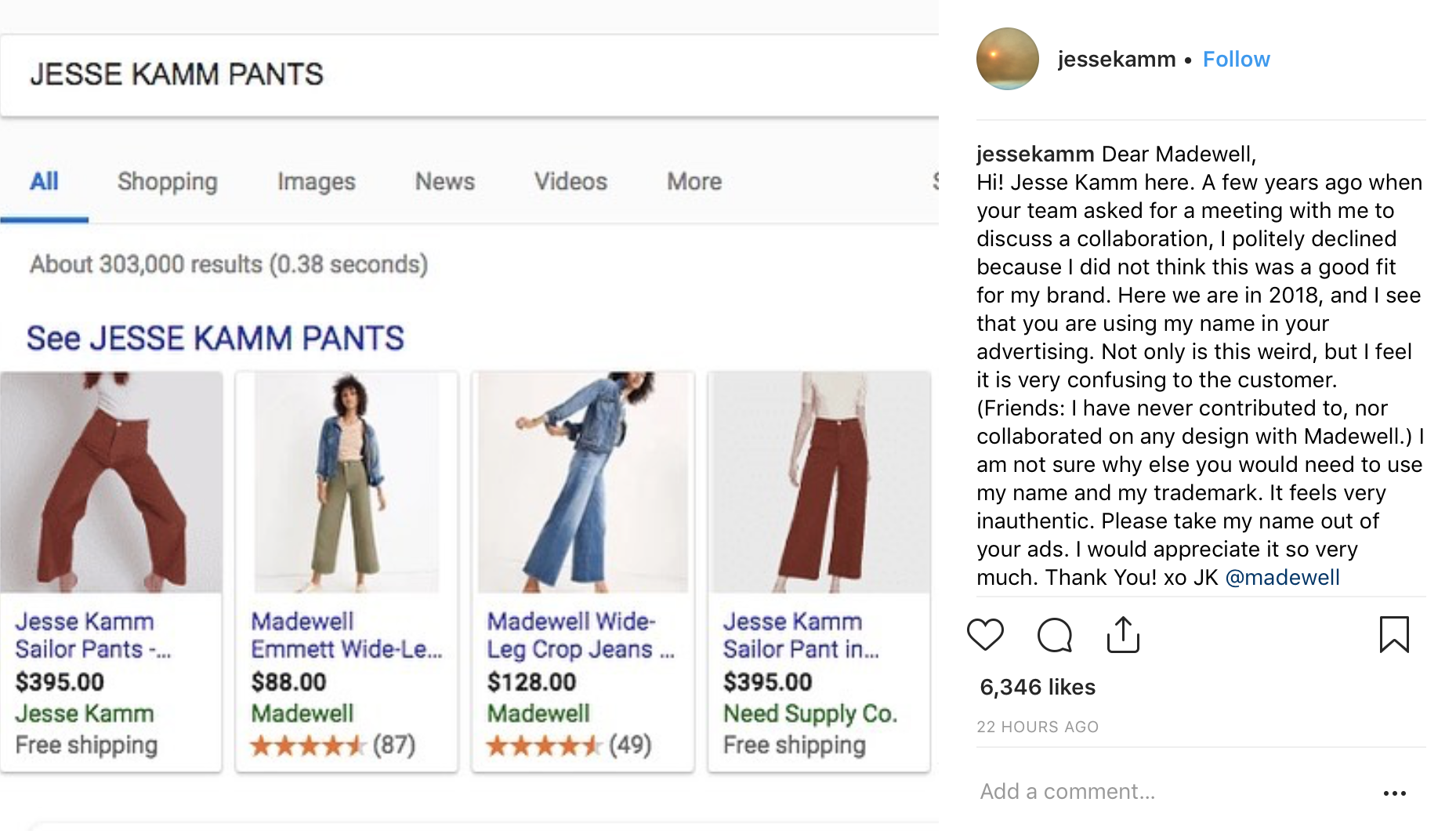

“Dear Madewell, I am not sure why you would need to use my name and my trademark … Please take my name out of your ads.” This is what California-based designer Jesse Kamm had to say – in an Instagram post on Tuesday – upon learning that when you Google her name, the results consist of her signature high-waisted “Kammpants,” as well as lookalike trousers from Madewell.

While it appears as though, in an effort to presumably boost traffic to its site and sell more of own its less expensive high-waisted pants (which Kamm says are not the result of a collaboration with Madewell), the retailer has been utilizing paid-for keywords, the reality of the situation is a bit different.

Instead of specifically targeting Jesse Kamm’s brand by bidding on her name as an ad word – which is a marketing practice widely-used by brands attempting to cut through the highly-saturated web and target consumers, and the core of what Google’s AdWords service provides – Madewell is doing something else. It is using Google’s Product Listing Ads (“PLAs”), a separate Google advertising service, and one that operates quite a bit differently.

Welcome to the complicated world of search engine advertising.

Essentially what is really going on here is this: Google, by way of its PLA service, offers companies selling products online the opportunity to advertise their products by bidding on various categories (such as “Jeans” or “Jeans under $200”). Unlike Google’s AdWords service, which operates based on keyword bidding, PLA campaigns function based on product and category bidding.

As such, it seems that Google’s algorithm is actually the one that identified the visual similarity between the two parties’ pants and potentially taking into account the searching party’s search history, suggested – based on Madewell’s utilization of its PLA service (presumably in categories related to high-waisted pants) – that the searching party might be interested in both the Jesse Kamm pants and some similar alternatives.

Kamm’s Instagram post suggests that Madewell made use of Google’s AdWords service, one in which brands and retailers seeking to attract consumers searching for “quilted bags,” “running sneakers,” or “red lipstick,” for instance, will purchase these words so they their handbag, sneaker, and lipstick products are favored in the search results. Smart marketers have since taken the practice of purchasing keywords a step further and are using descriptions of their rivals’ products – or even their competitors’ brand names – in order to entice online shoppers.

It is against this background (one that assumes that Madewell was specifically using her name to market its pants) that Kamm claims that Madewell’s alleged use of her name is “very confusing to the customer.” Asserting consumer confusion is, as the legally-minded amongst us will know, another way of claiming trademark infringement, as the likelihood that consumers will be confused as to the source of a product or a potential affiliation between parties in connection with a product as a result of the use of another party’s trademark is at the center of a trademark infringement inquiry.

For the sake of a hypothetical, since it is not unheard of for brands to utilize AdWords in this way (meaning that Kamm is not alone in arguing that the use of her name (i.e., her trademark) on competing products is both undeniably sneaky and likely to be confusing for consumers), let us unpack would it would mean – legally speaking – if that is what Madewell as actually doing

The Law (of AdWords)

Courts in the U.S. have been wrestling with issues involving keyword advertising and trademark infringement for quite a few years now.

Initially, courts tended to side with the so-called infringers (aka, the ones making use of other brands’ names as keywords), finding that use of a trademark in an advertising keyword manner does not constitute “use in commerce” that is capable of giving rise to trademark infringement in the first place. Courts across the U.S. have since agreed that this is actually a non-issue and that keyword use is, in fact, “use in commerce” and as a result, can give rise to potentially merited claims of trademark infringement.

Nowadays, the “overwhelming majority of courts have sided with the defense in these cases — with a lack of a likelihood of confusion as their primary basis,” according to Maral Kilejian and Sally Dahlstrom of Haynes and Boone LLP.

Up for debate instead of whether advertising keywords are sufficient “use” is what exactly the test for gauging consumer confusion in an ad word scenario should be. “The exact ‘likelihood of confusion’ factors may vary by jurisdiction, [but] one thing is clear: time and time again, courts analyzing likelihood of confusion in Internet keyword advertising cases find that purchasing a competitor’s trademark as a keyword ad trigger does not lead to a likelihood of confusion,” Kilejian and Dahlstrom state.

They further noted, “Since 2011, plaintiff wins [in] trademark infringement [cases] involving keyword advertising have been rare,” and part of this is due to the fact that most internet-using consumers are well-versed in how search engines’ sponsored results work.

That is probably not very good news for Kamm in our hypothetical scenario.

It would, however, be good news for consumers. Trademark law and modern competition policy, alike, recognize that at the core of their purpose is to promote competition, in large part for the benefit of consumers. With this in mind, University of Chicago Law School professor David S. Evans stated in a 2012 article, “Economists have found overwhelmingly that this type of informative and comparative advertising” – namely, how for searches for products or services using search engines help inform consumers about other competitive alternatives and enable them to compare different product offerings – “benefits consumers and, conversely, that restricting such advertising harms consumers.”