The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office is starting to work its way through the throngs of metaverse-centric trademark applications for registration that companies have rushed to file over the past year and a half amid an enduring rise in interest in the virtual world. Part of that process has seen the trademark office issuing Notices of Allowance – preliminary green-lights of sorts – in response to an array of intent-to-use applications, such as those filed by companies like Fashion Nova, Allbirds, Telfar, and Aime Leon Dore, which are looking to use their names and/or logos on “downloadable virtual goods” (in Class 9), “retail store services featuring virtual goods” (Class 35), and/or “entertainment services, namely, providing on-line, non-downloadable virtual [goods],” etc. (Class 41) in order to cater to consumers in the virtual world.

Save for some modifications to the language they use to describe the goods/services at play (in order to clarify things like “the type of virtual goods [that] are being provided and for what purpose”), which has proven a common response, the applications for registration filed by the likes of Allbirds, Aime Leon Dore, and co. have been given the go-ahead, with the companies receiving written notification from the USPTO that their marks survived the opposition period and have consequently been “allowed.” (The applications are now on hold for a 6-month period or until the companies can show that they are using the marks in commerce or until they file an extension request.)

Not all applications have sailed through the process thus far, though. In fact, a growing number of metaverse and/or non-fungible token (“NFT”)-focused trademark applications are facing pushback from with USPTO, with examining attorneys for the national trademark office taking issue with certain applications on the basis of likelihood of confusion between the metaverse-related marks at issue and previously-registered marks (for “real world” goods/services). Other refusals have seen examining attorneys take issue with whether the applied-for mark functions as a trademark, and thus, can be registered as one.

MODAVERSE & “Meta Gala” Marks

In terms of likelihood of confusion, which is a bar against registration, examining attorneys have called foul on NFT and/or metaverse-specific trademark applications filed by companies, such as Moda Operandi and Virtual Brand Group, Inc., on this basis. In February, for instance, the USPTO took issue with Moda Operandi’s intent-to-use application for “MODAVERSE” for use in “conducting virtual trade show exhibitions online in the field of fashion for fashion designers and fashion labels seeking to sell excess inventory,” along with NFTs and “streamble fashion content” (Class 35), and real-world “personal stylist services” (Class 45).

According to USPTO examining attorney Monica Beggs, the high fashion retailer’s mark is likely to cause confusion with “MODAVERS,” which was registered to an unaffiliated individual in 2018 for use on “printed matter, namely, photographs, magazines, books, and brochures, all in the field of fashion” (Class 16). The two marks, themselves, are “nearly identical,” Beggs said in the February 2022 Office action. She also found that the parties’ goods and services “are considered related for likelihood of confusion purposes,” noting that there are entities that offer up both personal styling services and fashion-centric printed materials, as well as those that offer up “streamble fashion content” and fashion-centric printed materials.

While Beggs makes no mention of the similarity (or potential lack thereof) between NFTs and/or “conducting virtual trade show exhibitions online” and fashion-centric printed materials, she, nonetheless, refused registration. Moda now has the opportunity to argue that its use of the “MODAVERSE” mark is not likely to cause confusion.

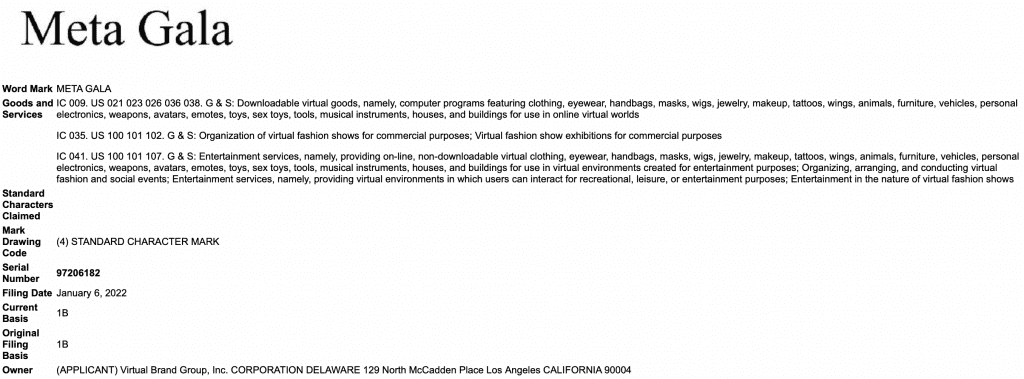

In a separate – and potentially, even more interesting – example, Virtual Brand Group (“VBG”), a company that partners with companies to “design, build, operate, market and monetize [their brands] across the metaverse,” filed an application for “Meta Gala,” which has been preliminarily shut down by the USPTO. The basis? VBG’s mark – which it intends to use for “organizing, arranging, and conducting virtual fashion and social events; Entertainment in the nature of virtual fashion shows” (in Class 41) – is too similar to “Met Gala,” a trademark that the Metropolitan Museum of Art has maintained rights in since the 1980s and a registration for since 2020. (The Met’s registration covers the “arranging, organizing, conducting and hosting [of a] social entertainment event” – also in Class 41.)

One of the key takeaways here is that in rejecting VBG’s application (on a non-final basis) late last month, USPTO attorney Max Faucette determined that while the Met has primarily staged its annual gala in physical form, its rights in – and registration for – “Met Gala” and similar marks extend to uses in the virtual world. “In this case,” Faucette stated that the Met’s registration “uses broad wording to describe ‘arranging, organizing, conducting and hosting social entertainment event,’ which presumably encompasses all goods and/or services of the type described, including applicant’s narrower ‘organizing, arranging, and conducting virtual fashion and social events; Entertainment in the nature of virtual fashion shows.’”

This drives home the point we made early this year that while brands have been rushing to file metaverse and NFT-specific applications for the marks they are already using in the “real world,” chances are, their existing registrations will probably cover “the most predictable” uses of their marks in the metaverse. This also seems to be what Judge Jed Rakoff of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York suggested in a recent order in the trademark case suit that Hermès lodged against MetaBirkins-maker Mason Rothschild, in which he stated that a traditional trademark infringement analysis (as opposed to one that entails the Rogers test) might be used in the event that an unaffiliated party made use of the “Birkin” trademark on virtual handbags (as opposed to static images tied to NFTs).

The Ralph Lauren Refusal

Likelihood of confusion is not the only basis that USPTO examining attorneys are citing in preliminary refusals to metaverse trademark applications. In response to one of the applications lodged by counsel for Ralph Lauren in December, a relatively rare application that claims actual use (as opposed to intent-to-use), examining attorney Christina Calloway asserts that the company’s polo player logo “as used on the specimen of record, does not function as a service mark to identify and distinguish applicant’s services from those of others and to indicate the source of applicant’s services.” The services here are “retail store services featuring virtual goods, namely, clothing and accessories for use in online virtual worlds” (Class 35) and “Entertainment services, namely, providing on-line, non-downloadable virtual clothing and accessories for use in virtual environments created for entertainment purposes” (Class 41).

In an Office action in April, Calloway claims that the applied-for mark does not function as a service mark because “it appears as an ornamental feature of the virtual goods provided by [Ralph Lauren’s] services,” or in other words, the specimens – which consist of screenshots from Ralph Lauren’s gaming venture with Roblox, namely, an avatar wearing a polo logo-bearing shirt and a collection of garments, each with a polo icon next to it – do not show the mark used in a manner that would indicate the source of the services.

With that in mind, Calloway states that Lauren can either submit a new specimen (that does not depict the logo in an ornamental way) or amend its filing basis to 1(b). The brand’s next moves on this front will be closely watched – for sure, as brands across the board (most of which filed their metaverse-related applications on an intent-to-use basis and thus, without showing actual use in commerce) will undoubtedly be looking for guidance when it comes to what the USPTO views as acceptable specimens of use in the virtual world.