Deep Dives

Retail is rife with legal battles that pit industry occupants – from luxury brands to sportswear titans – and their valuable trademarks against one another. With the first half of the year behind us, here is a look at a number of currently pending trademark cases that are worth keeping a close eye on, as brands clash over the use of their trademarks in connection with the marketing and sale of non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”), Chanel continues to face off against a couple of resale entities, footwear brands wage lawsuits over their trademarks (and trade dress), and celebrities and other big companies are slapped with reverse confusion-focused suits over newly-launched (or in Meta’s case, relatively newly-rebranded) endeavors.

No shortage of these cases are expected to provide guidance for brands and trademark practitioners, alike, with matters that are being waged over the use of marks on virtual goods/services (i.e., in the metaverse) and/or in connection with NFTs, likely to be especially useful in helping to lay the groundwork for future actions in this space.

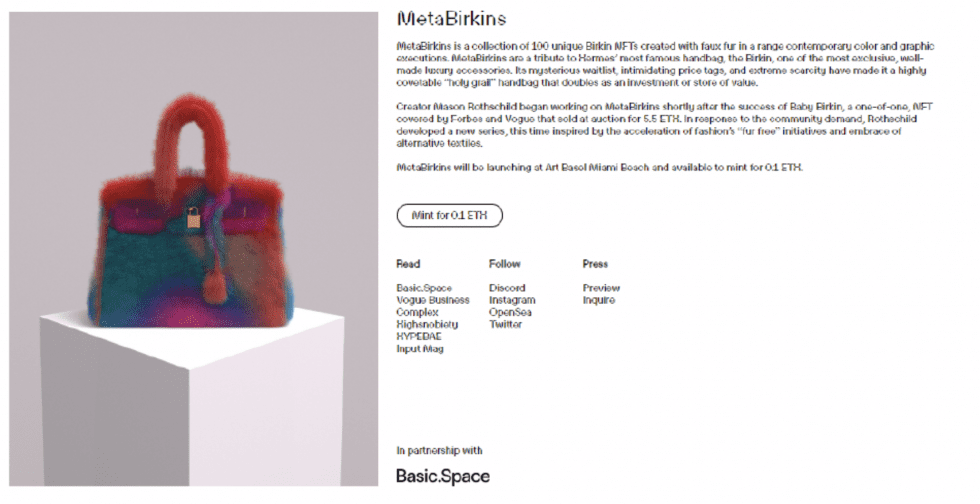

In one of the first headline-making cases involving NFTs, Hermès filed a trademark infringement, federal trademark dilution, false designations of origin, false descriptions and representations, cybersquatting, injury to business reputation, misappropriation, and unfair competition lawsuit against Mason Rothschild, the individual behind the collection of 100 MetaBirkins NFTs, early this year. Tied to images depicting furry renderings of its famous Birkin bag, Hermès claims that in furtherance of his sale of the NFTs, Rothschild simply “rip[s] off [its] famous BIRKIN trademark by adding the generic prefix ‘meta,’” which refers to “virtual worlds and economies where digital assets such as NFTs can be sold and traded.”

Rothschild has since argued that his “fanciful depictions of fur-covered Birkin bags and his identification of his artworks as ‘MetaBirkins’ are artistically relevant and do not explicitly mislead about their source or content,” and thus, should be protected from trademark liability by the First Amendment. While the court agreed that the Rogers test should be used to determine whether Rothschild’s use of Hermès’ marks is actionable under the Lanham Act, SDNY Judge Jed Rakoff determined in May that Hermès has sufficiently set out allegations that Rothschild’s use of “MetaBirkins” is not artistically relevant or is explicitly misleading and therefore, fails to meet the Rogers test.

Counsel Rothschild lodged a memo of law in support of “an immediate interlocutory appeal” in early June, arguing that the case addresses “an issue being closely watched by the press because it is of special consequence to society at large and art markets in particular: whether artists are free under the First Amendment to depict or refer to trademarks in their art, and to describe what they have depicted, without fear of trademark liability.” Hermès subsequently pushed back in a memo of its own.

The case is Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, 1:22-cv-00384 (SDNY).

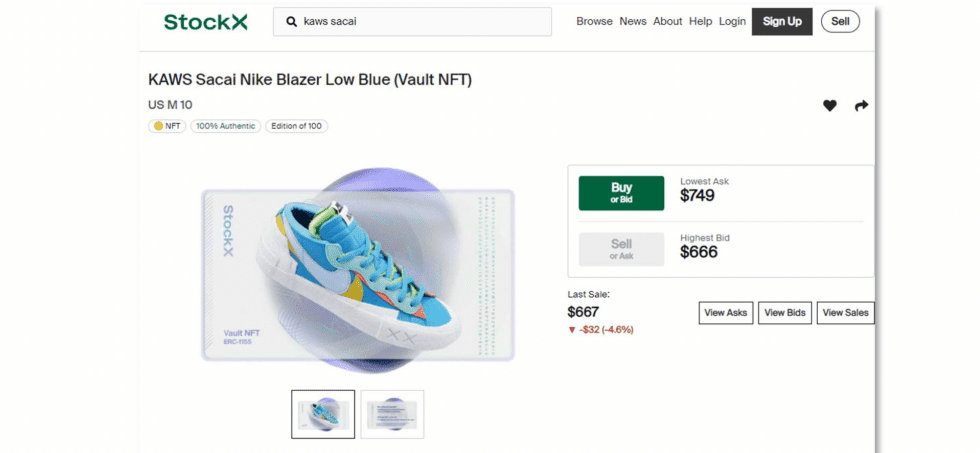

Nike filed suit against StockX early this year, alleging the Detroit-based marketplace is on the hook for trademark infringement and dilution, as well as unfair competition, in connection with its offering up of “Vault NFTs” tied to images and physical versions of Nike footwear – albeit without receiving its authorization. To make matters worse, Nike claims that StockX is “selling those NFTs at heavily inflated prices to unsuspecting consumers who believe or are likely to believe that those ‘investible digital assets’ (as StockX calls them) are, in fact, authorized by Nike.” (Nike amended its complaint in May to add counterfeiting and false advertising claims.)

Among the interesting elements of the case is whether the court will side with StockX in terms of its argument that the NFTs are little more than “claim tickets” or “digital receipts” used to “track ownership of a specific physical Nike product that StockX has purportedly authenticated process’” – and thus, the sale of the sneakers (and corresponding NFTs) falls firmly within the realm of the First Sale Doctrine.

Also worth noting: Nike takes issue with StockX’s practice of claiming that the Vault NFTs are “100% Authentic” and that the NFTs help “track ownership of a specific physical Nike product that StockX has purportedly authenticated using its ‘proprietary, multi-step authentication process.’” These claims, according to Nike, are “intended to explicitly mislead consumers” into believing that Nike has “authorized, approved, sponsored, and/or endorsed StockX’s Vault NFTs” when no such affiliation exists. Nike further takes issue with StockX’s claims about its “proprietary multi-step verification process,” “100% Verified Authentic” offerings, and “authentication accuracy rate of ‘99.95%” in light of its purchase of alleged counterfeit goods from the StockX platform.

If these arguments sound familiar, it is likely because Chanel has made relatively similar ones in its case against The RealReal.

The case is Nike, Inc. v. StockX LLC, 1:22-cv-00983 (SDNY).

Chanel’s cases against The RealReal (“TRR”) and What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”) are still underway in the SDNY roughly four years after the cases were filed – with the parties in both cases currently clashing over discovery.

In the enduring trademark and anti-competition lawsuit that Chanel filed against TRR, the brand accuses the resale platform of “selling counterfeit CHANEL handbags, while also “represent[ing] to consumers that it ‘ensure[s] that every item on TRR is 100% the real thing, thanks to our dedicated team of authentication experts,’” and then offering up and selling a number of “counterfeit” Chanel products. Chanel has also taken issue with TRR’s “advertising and marketing practices,” claiming that the reseller “has attempted to deceive consumers into falsely believing that [it] has some kind of approval from or an association or affiliation with Chanel” when no such association exists.

Following a stay in the case while the parties participated in a mediation with the aim of a settlement, counsels for the two companies alerted an SDNY judge in December 2021 that they were “unable to reach a resolution of the matter at this time.” As of July 1, the parties were slated for a discovery hearing, including on whether certain documents should be clawed back as privileged, as Chanel has argued.

Meanwhile, Chanel is still embroiled in the separate – but similar – case that it filed against WGACA. After refusing to toss out the bulk of Chanel’s claims, including its trademark infringement and false association causes of action, a New York federal court ordered that the New York-based reseller provide additional information about its sale of Chanel-branded products. In an order in June, SDNY Judge Louis Stanton ordered WGACA to produce the monthly financial statements dating back to 2018 that its expert used to calculate WGACA’s profits, along with its summary of Chanel-branded product “sales and costs,” along with updated “Google Analytics information, data from Bitly, and internal reports relating to WGACA’s advertising using Chanel’s trademarks” – and the effectiveness of such ads.

Reflecting on the significance of the cases, Foley & Lardner’s Jeffrey Greene and Allison Haugen have stated that the implications “could be broad-reaching, providing guidance to resellers on the parameters of a fair use defense to trademark infringement claims.” They also stand to provide “insights into the validity of antitrust-type claims in instances of claimed interference with the resale market, particularly in connection with Chanel v. The RealReal, as well as how resellers ought to describe the authenticity of the goods they sell.”

The cases are Chanel, Inc., v. The RealReal, Inc., 1:18-cv-10626 (SDNY), and Chanel, Inc. v. What Goes Around Comes Around, LLC, et al., 1:18-cv-02253 (SDNY).

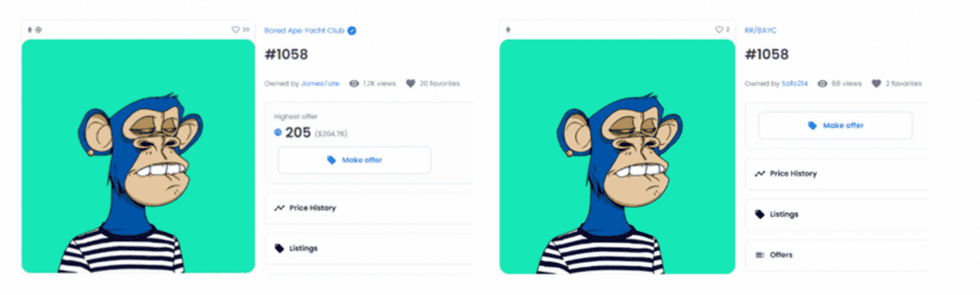

The company behind the popular collections of Bored Ape Yacht Club tokens is suing a group of defendants, including Ryder Ripps in a headline-making trademark case, accusing the artist and other defendants of “trolling Yuga Labs and scamming consumers into purchasing RR/BAYC NFTs by misusing Yuga Labs’ trademarks.” In the complaint that it filed in a California federal court on June 24, Yuga Labs claims that Ripps, Jeremy Cahen, and a number of other affiliated defendants are on the hook for trademark infringement, false designation of origin, cybersquatting, and conversion for creating and selling NFTs that bear “the very same trademarks that Yuga Labs uses to promote and sell authentic BAYC NFTs.”

In furtherance of his alleged quest to “devalue the Bored Ape NFTs by flooding the NFT market with his own copycat NFT collection using the original Bored Ape Yacht Club images and calling his NFTs ‘RR/BAYC’ NFTs,” Yuga Labs alleges that Ripps has reaped “millions of ill-gotten profits from these sales” (an estimated $5 million), all while simultaneously using its trademarks to promote “the imminent launch of an entire NFT marketplace called ‘Ape Market’ solely to sell the RR/BAYC NFTs alongside authentic Yuga Labs NFTs.”

Yuga sets out claims of common law trademark infringement (as its long list of BAYC-centric trademark applications are still pending before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office), false designation of origin and false advertising under the Lanham Act, cybersquatting, conversion, unjust enrichment, violations of California Business and Professions Code, intentional interference with prospective economic advantage, and negligent interference with prospective economic advantage. (Note: Yuga does not appear to have any copyright registrations for its ape images and does not claim copyright infringement in its complaint.)

The deadline for Ripps and co. to file their answer (or 12(b) motion) has been extended to August 29.

The case is Yuga Labs, Inc. v. Ryder Ripps, et al., 2:22-cv-04355 (C.D. Cal.)

Also worth watching out for: a potential class action for Yuga over its Bored Ape NFTs and ApeCoin tokens. Scott + Scott issued a release, stating that “Yuga Labs individual investors are now joining together through a class action” in light of Yuga allegedly “us[ing] celebrity promoters and endorsements to inflate the price of the company’s NFTs and token, by generally promot[ing] the growth prospects and change for huge returns on investment to unsuspecting investors.”

A few new trademark infringement cases have popped up in recent weeks, with the plaintiffs all alleging that newer-but-much-bigger brands are giving rise to reverse confusion. SKKN+ owner Beauty Concepts LLC, for example, filed against the much-more-famous Kim Kardashian ahead of the launch of her brand SKKN by Kim, and there is also the case that 8-year-old fashion brand Rhode recently filed against Hailey Bieber, the widely-known model and wife of musician Justin Bieber, over her new skincare brand Rhode. In both cases, the plaintiffs argue that they took an immediate hit following the launch of the defendants’ brands. In the SKKN by Kim case, for instance, SKKN+ claims that while it had previously “achieved a top ranking in an online search, which takes time, investment, and customer awareness for a small business to achieve,” its “online presence has been overwhelmed by the defendants’ online advertising.” Rhode similarly claims that in the wake of the launch of the Bieber’s brand, search engine query results for the word “rhode” have been dominated by the defendants’ brand instead of its own.

And in what might prove to be an even bigger case, Meta Platforms, Inc. (the company formerly known as Facebook, Inc.) landed on the receiving end of a new lawsuit in the SDNY, with a small virtual reality-focused company accusing it of “brazenly violat[ing] fundamental intellectual property rights enshrined in U.S. law to obliterate” a business that has been using the Meta name for more than ten years. In the lawsuit that it filed in a New York federal court on July 19, experiential and immersive technologies company Meta claims that in opting to rebrand to “Meta” last fall, Facebook, Inc. “astoundingly … ignored [its] federal registrations for the META mark,” and the company has since “saturate[d] the marketplace with its infringing META mark,” leaving Meta with little chance to survive.

The budding number of reverse confusion-focused cases being filed in federal district courts in New York stand to bring some guidance for both plaintiffs and defendants should they seek to lodge – or be forced to defend – similar cases, particularly as most of the most closely-watched reverse confusion cases have been litigated in district courts that fall within the jurisdiction of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, not the Second Circuit. A recent exception is, of course, RiseandShine Corporation v. PepsiCo, Inc., in which the Second Circuit reversed a preliminary injunction entered by the SDNY barring PepsiCo from marketing its “Mtn DEW Rise Energy” energy drink.

Taking issue with the merits of Rise Brewing’s reverse confusion theory, among other things, the Second Circuit disagreed with the lower court in terms of the strength of Rise Brewing’s mark, finding that links between the word “Rise” and coffee make it a suggestive mark entitled to a narrow scope of protection. Beyond that, the appeals court agreed with PepsiCo’s argument that “where a plaintiff claims it will be the victim of reverse confusion – in that consumers will believe that its product comes from the junior user – a plaintiff’s showing of acquired strength of its mark does not support its claim.”

The cases are Beauty Concepts LLC v. Kim Kardashian West, et al., 1:22-cv-03797 (EDNY), Rhode-NYC, LLC v. Rhodedeodato Corp. et al, 1:22-cv-05185 (SDNY), and METAx LLC v. Meta Platforms, Inc., 1:22-cv-06125 (SDNY).

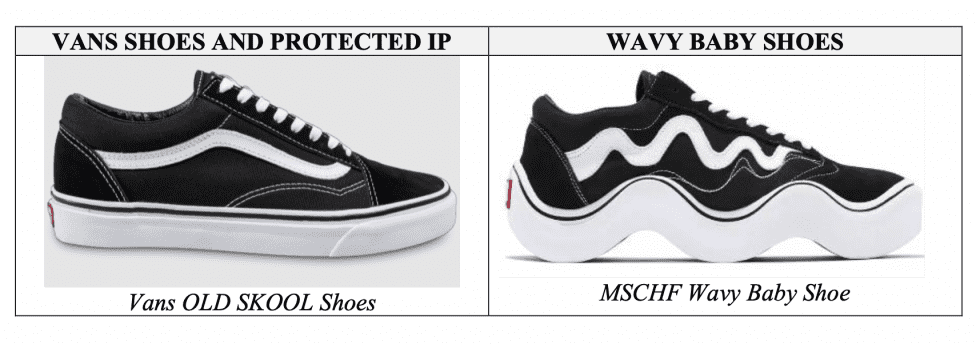

Just over a year after settling the trademark-centric lawsuit waged against it by Nike, MSCHF landed on the receiving end of a new lawsuit. In the complaint that it lodged with the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York in April, Vans and its parent company VF Corp. allege that MSCHF “embarked on a campaign to piggy-back on Vans’ rights and the goodwill it has developed in its iconic shoes” by offering up a shoe of its own that “blatantly and unmistakably incorporates Vans’ iconic trademarks and trade dress” for its 40-year-old OLD SKOOL shoe, including the “Side Stripe” trademark.

“The combination of elements comprising the OLD SKOOL trade dress is distinctive, and the public recognizes and understands that the OLD SKOOL trade dress distinguishes and identifies genuine Vans brand shoes,” the footwear brand asserts. “As a result of Vans’ extensive use of the OLD SKOOL trade dress,” including sales of “hundreds of millions of shoes bearing the side stripe mark,” which have accounted for “tens of billions of dollars in revenue,” Vans claims that it “has built up and now owns extremely valuable goodwill that is embodied by the OLD SKOOL trade dress.”

MSCHF’s Wavy Baby sneakers are an example of a “cultural readymade, a mass-produced object modified to create expressive art,” and should be protected as such, the Brooklyn-based art collective-slash-sneaker brand asserted in its answer, claiming that its offerings – including the Old Skool-inspired Wavy Baby sneakers – “are not mere consumer goods,” but instead, are part of a larger “series of expressive works using shoes as a medium for its art.”

Among other things, the case has spawned an interesting focus on the applicability of the Rogers test, with the International Trademark Association urging the Second Circuit (by way of an amicus brief in June) to confirm that the test applies “only to traditionally expressive works, not ordinary consumer products” … like sneakers. (More about that here.) The case is slated to get a Second Circuit intervention, as MSCHF is appealing the lower court’s grant of a preliminary injunction barring it from marketing, displaying, offering up and/or fulfilling existing orders for its allegedly infringing Wavy Baby sneakers.

Vans is also embroiled in a separate trademark fight involving its OLD SKOOL trade dress, which it is waging against Walmart, accusing the retail titan of embarking on “an escalating campaign to knock off virtually all of [its] bestselling shoes,” and running afoul of its trademark rights in the process. Vans scored a preliminary win in March when a California federal court granted its motion for a preliminary injunction, ordering Walmart to refrain from offering up footwear that bears Vans’ trademarks, including almost 30 allegedly infringing shoe styles that it has offered up in the past for the duration of the case.

The cases are Vans, Inc. v. MSCHF Product Studio, Inc., 1:22-cv-02156 (EDNY), and Vans, Inc. et al, v. Walmart, Inc., et al, 8:21-cv-01876 (C.D.Cal.).

And no list of pending trademark cases would really be complete without a battle over adidas’ stripes. The German sportswear giant filed suit against Thom Browne in June 2021, setting out claims of trademark infringement, unfair competition, and dilution, and alleging that Thom Browne is “encroach[ing] into direct competition with [it] by offering sportswear and athletic-styled footwear that bear confusingly similar imitations” of its tfamous hree-stripe mark.

On the heels of a New York federal court refusing to toss out the case, Thom Browne filed its answer this spring, complete with affirmative defenses, in furtherance of which the fashion brand has argued that it should be shielded from liability because adidas failed to take action against it over its use of a 4-stripe pattern – which has appeared on Thom Browne wares since 2009 – in a timely manner. Thom Browne also lodged a counterclaim aimed at getting adidas’ “Three-Quadrilaterals Design” trademark registration canceled. Citing the Second Circuit’s 2012 decision in Louboutin v. Yves Saint Laurent, Thom Browne argues that the court should invalidate the registration on the basis of aesthetic functionality, under which, a mark is ineligible for trademark protection “if granting the owner the exclusive right to use the mark ‘would put competitors at a significant non-reputation related disadvantage.’”

More recently, adidas filed a motion to dismiss the counterclaim, arguing that Thom Browne fails to allege that “the particular iteration” of adidas’s famous 3-stripe mark is, in fact, aesthetically functional, and instead, alleges that “any ‘parallel stripes’ design is aesthetically functional.”

The case is adidas America, Inc., et. al., v. Thom Browne, Inc., 1:21-cv-05615 (SDNY).