Deep Dives

Among the digital items and crypto collectibles that users can bid for and/or buy outright on non-fungible token (“NFT”) marketplaces like Opensea and Rarible are a sweeping array of crypto domain names. If you search for “Chanel” or “Hermès” on OpenSea, for instance, you will find NFTs tied to domains bearing the brands’ famous names up for offer. Chanel.eth currently boasts a price tag of 300 ETH ($924,794), while hermes.eth can be bought for 250 ETH ($788,435.00). The same goes for domains bearing the trademarks of Gucci, Prada, Dior, Balenciaga, Rolex, and other similarly situated brands, along with companies ranging from sportswear titan Nike to Italian automaker Ferrari.

Ethereum Name Service (“ENS”) domains (i.e., those that end in .eth) represent unique addresses on the Ethereum blockchain, which can be used to easily receive any type of cryptocurrency and/or token, including NFTs, to a crypto wallet. These ENS domains and others decentralized domains do not function entirely differently than their .com counterparts in that, like the traditional DNS system, they act as human-readable names for less straightforward addresses.

There are, however, some distinctions between DNS and crypto domains – from where the addresses point (typically to crypto wallets for crypto domains, but also websites that reside on a decentralized internet) to how governance is handled. Unlike DNS domains, for instance, blockchain-based web domains are not governed by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (“ICANN”) and thus, are not subject to its procedures, such as the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy and the Uniform Rapid Suspension System.

This means that while blockchain-based domains provide users with benefits, such as an easy-to-use alternative to a long, alphanumeric crypto wallet address (think: 0xb15166d10aebc6bb4868668eff1b3acd95da920c) and heightened security since they are created with blockchain-hosted smart contracts, there are some potential drawbacks. For one thing, trademark holders are not able to utilize ICANN proceedings when it comes to the bad-faith registrations or otherwise infringing uses of these domain names. At the same time, “Blockchain-based naming systems often have no central authority that can provide a remedy to aggrieved brand owners,” according to Sterne Kessler’s Dan Bernard and Monica Riva Talley, and “the anonymity that blockchains provide typically means that squatters cannot be identified in order to take legal action in any forum.”

The very decentralized nature of blockchain-based domains “makes them attractive to a new breed of squatters and digital land grabbers – not least because they can be nearly impossible to police for infringement of trademark rights,” Bernard and Talley have noted. Unsurprisingly, “One of the purported ‘next big things’” in this space “harkens back to one of the ‘old big things’ in the gold rush of the dot-com boom two decades ago,” per Bloomberg’s senior markets editor Michael Regan. In other words, domain-name squatting … albeit not in Web2 for .com domains but in Web3 for those bearing suffixes like .eth, .crypto, .coin, .dao, .nft, .sol, etc.

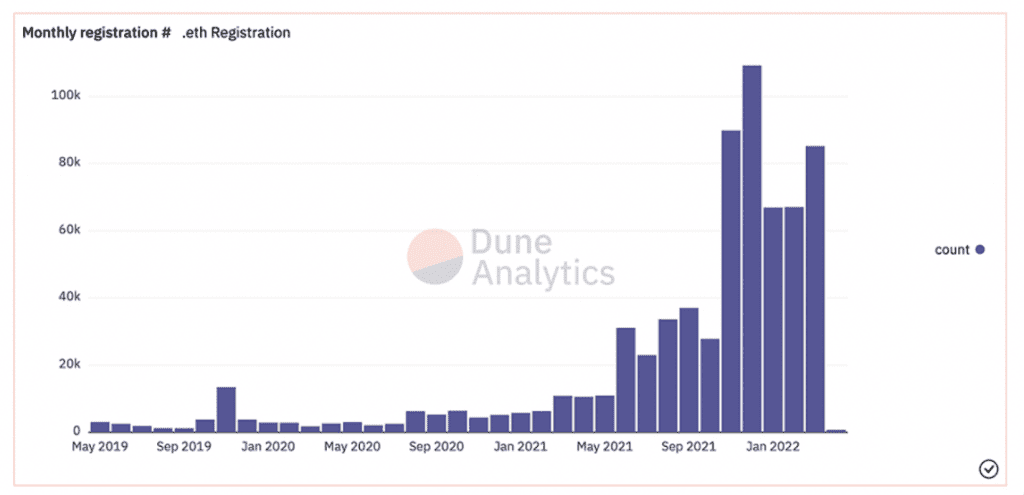

The rush to claim blockchain domains – which saw 85,000 new .eth domains registered in March bringing the total number of .eth domains, alone, to 825,000 – is raising questions and posing risks for well-known brands and other trademark holders, whose names are being brought into the fold.

The potential for harm is worthy of attention, as if a trademark is being used in a crypto domain name without the trademark owner’s authorization, “there is a significant risk that the owner of the domain name can purport to offer the brand’s crypto wallet and/or enter into financial transactions or smart contracts, allegedly on behalf of the brand,” according to MMX general counsel Sheri Falcon. This is particularly noteworthy in light of the growing number of brands that are beginning to embrace crypto as a form of payment for their goods/services (Off-White is the latest), with many others expected to follow suit. (Think “apple.eth” for the purchase of an iPhone with cryptocurrency in the future – or perhaps, the future online store for Apple products, Harness IP’s Matthew Cutler hypothesizes.)

Such harm is heightened by the fact that while certain blockchain domain naming companies, such as Unstoppable Domains, have implemented sunrise periods for domains associated with “well-known entities, products, or individuals” in an attempt to avoid squatting, there does not appear to be a mechanism for challenging unauthorized use of a trademark-bearing domain with such blockchain-domain registrars. (Unstoppable Domains, for one, states in its terms that users must “not to violate or infringe the rights of UD, our users, or others, including privacy, publicity, intellectual property, or other proprietary rights,” but lacks terms about trademark infringement recourse.)

Against this background, trademark holders looking to take action over blockchain-based domains will have to look elsewhere.

In addition to obstacles to bringing litigation to prevent unauthorized use of blockchain domain names when it is impossible to ascertain the identity of the owner, which “presents challenges in determining the proper party, jurisdiction, and venue” in an action, Kelley Drye’s Andrea Calvaruso, Matthew Luzadder, Constantine Koutsoubas, and Kerianne Losier stated in a recent note that the Lanham Act’s Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act, which “provides in rem jurisdiction over domain names themselves in certain circumstances where there is no personal jurisdiction over the defendant who owns the domain name,” may not prove to be useful. Such jurisdiction “is only possible in judicial districts where the registrar or other domain name registry or authority that issued the domain name is located,” and often, this is not in the U.S.

With all of this in mind, the most viable approach as of now is one that targets the sale of the domains as NFTs on marketplace sites. Takedown actions are offered by sites like OpenSea and are already being used by a number of luxury brands to put a stop to the sale of allegedly infringing crypto domains. At the same time, it is generally recommended that trademark holders consider acquiring blockchain domains of their own – from .eth to .nft – as a way to not only potentially prevent squatting but also reserve them for possible future use, which seems increasingly likely for brands across the board. (Just this week, Axel Dumas, the Executive Chairman of Hermès, told shareholders that management for the stalwart luxury brand is “curious about and interested in” the metaverse as a potential communication tool.)

THE BOTTOM LINE: Blockchain-based domains “present both opportunities and risks” for brands, according to Bernard and Talley, and so, companies should be treating these “new unregulated spaces as free markets that need to be monitored for opportunities and addressed proactively.”