Some of the earliest trademark applications filed by the company behind Bored Ape Yacht Club could provide some insight into what brands can expect when it comes to their own trademark applications for non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) and the “metaverse” more generally. Yuga Labs – the $4 billion force behind the collection of 10,000 Ethereum-hosted Bored Ape NFTs owned by the likes of Serena Williams, Snoop Dogg, Mark Cuban, Madonna, Gwyneth Paltrow, Paris Hilton, and Alexis Ohanian, among others – filed a number of Bored Ape Yacht Club (“BAYC”)-centric applications for registration with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”), including one for “Bored Ape Yacht Club” back in May 2021, citing its use of the word mark in a trio of classes of goods/services dating back to April 23, 2021.

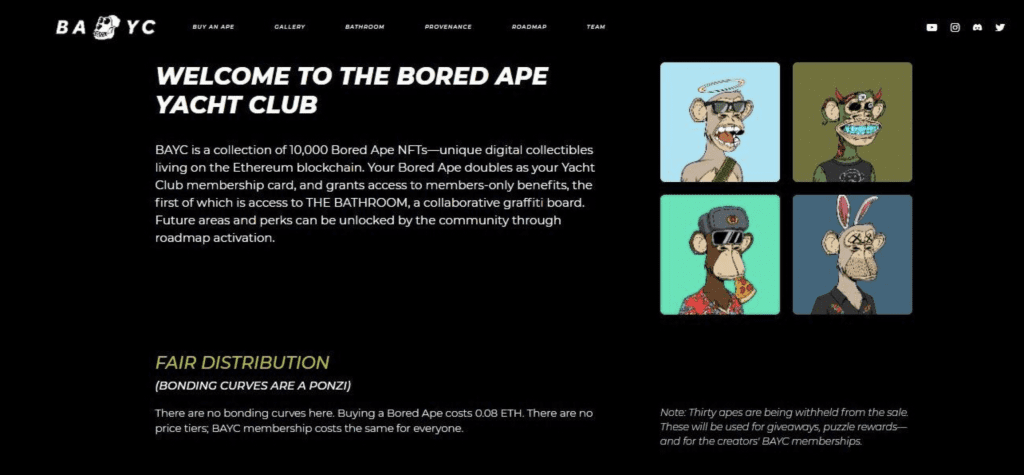

In its application, Yuga Labs claims rights in the Bored Ape Yacht Club trademark for use in connection with “digital collectibles; digital collectibles sold as non-fungible tokens” (Class 16), “maintain[ing] and record[ing] ownership of digital illustrations; maintain[ing] and record[ing] ownership of digital illustrations represented by non-fungible tokens; providing a website featuring an online marketplace for exchanging digital collectibles” (Class 35), and “online social networking services provided through a members-only website; computer services, namely, creating an online community for registered users to access a collaborative graffiti board” (Class 45).

Fast forward to March 23 and the USPTO has sent Yuga Labs an Office Action, preliminarily refusing to register the BAYC trademark on the basis of premature use (within Class 45) and unacceptable specimens across all three classes, while also requiring the Miami-based company to amend the identification of certain goods and services in its application and to include a disclaimer for the word “Club.”

The bulk of the USPTO’s pushback centers on the specimen that Yuga submits with its application, which consists of screenshots from the BAYC website that show the inside of the yacht club bar; that describe the BAYC collection, the membership access/benefits, and the community tools; and that set out “goalposts” for the project, such as “unlocking” the BAYC merch store, among other things.

Specifically, the USPTO’s examining attorney asserts that the specimen does not show use of the BAYC mark in Class 16 (i.e., in connection with “digital collectibles; digital collectibles sold as NFTs”), which could potentially be cured by Yuga by way of a screenshot that shows listings for the BAYC NFTs on a marketplace like OpenSea. (Although, it is not impossible to imagine the USPTO objecting to that on the basis that the listing are not coming from Yuga, itself, but the third-party owners of the NFTs.)

As for the other classes, the fix might be more difficult, with the USPTO stating that the specimen does not demonstrate the mark being used “in a way that would create in the minds of potential consumers a sufficient nexus or direct association between the mark and the services being offered.” The USPTO states that Yuga’s Class 35 services, for instance, include “maintain[ing] and record[ing] ownership of digital illustrations represented by non-fungible tokens,” which the company aims to show by way of “a provenance record of each of [the BAYC] NFTs.” This does not sufficiently establish such a nexus, according to the USPTO examiner, as “the record of ownership appears to be incidental to [Yuga’s] business,” and thus, it “does not appear to be providing this service for others.” (This is significant, as according to the Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure, in order for something to be considered a service, it “must be primarily for the benefit of someone other than the applicant.”)

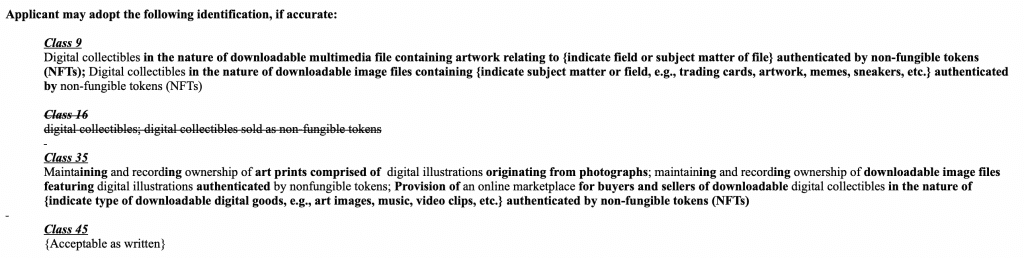

In pushback to the Yuga application that could apply broadly across the ever-growing list of applications for registration that have been lodged with the USPTO in recent months in connection with NFTs and virtual goods, the USPTO takes issue with the wording “digital collectibles” in Yuga’s Class 16 description, arguing that this identification of goods is “indefinite and must be clarified because it does not make clear what the nature of the goods are.”

For example, the examining attorney states that the term “collectibles” could encompass “a wide variety of goods in multiple classes,” and further asserts that “the nature of the goods as ‘digital’ must be clarified because Class 16 encompasses paper goods and printed matter.” The examining attorney states that Yuga “must amend this wording to specify the common commercial or generic name of the goods,” noting that “if the goods have no common commercial or generic name, applicant must describe the product, its main purpose, and its intended uses. “

The wording “digital illustrations” and “providing a website featuring an online marketplace for exchanging digital collectibles” in the identification of services in Class 35 is similarly “indefinite” and requires clarification because “it does not sufficiently indicate the nature of the goods and/or services,” according to the Office Action, which suggests that Yuga amend the Class 16 identification to a Class 9 identification, instead.

Examining attorneys for the USPTO have pushed back against additional BAYC-focused trademark applications filed by Yuga on similar grounds, stating in a separate Office Action on March 23 that an application for a mark that consists of “an ape skull facing left” for use in Class 9 (namely, NFTs) and Class 43 (“Non-downloadable virtual goods, namely, non-fungible tokens,” etc.), for example, stating that “registration is refused because the specimen does not show the applied-for mark as actually used in commerce in connection with any of the goods and/or services specified.” While Yuga’s Class 9 identification includes various non-fungible tokens, the specimen “does not indicate that applicant is providing these goods or services,” according to the USPTO, which notes that “the specimen provides a link to an external third party for the purpose of purchasing a piece of applicant’s NFT collection. Specifically, the page states “BUY AN APE ON OPENSEA,” [which] suggests that OpenSea is the source of applicant’s goods and/or services, not applicant.”

In light of the striking number of applications for registration that have been lodged with the USPTO by brands over the past year for NFTs and “digital collectibles,” as well as “virtual goods,” “downloadable items,” and “entertainment services,” the examining attorneys’ pushback against the BAYC trademark applications – and how that responds to changes that Yuga may opt to make in response to the Office Action – should provide insight into how the USPTO will treat other applications in this space, no shortage of which have been filed by brands that are often not entirely sure what their operations in the metaverse actually will look like or how the USPTO will treat their applications.