On the heels of Nike beating the motion to dismiss that was filed by John Geiger Collection, the Los Angeles-based brand has lodged counterclaims in its enduring fight against the sportswear giant. In a lengthy answer dated February 22, Geiger denies the bulk of Nike’s claims against it and sets out an array of affirmative defenses, arguing, among other things, that Nike’s trademark infringement, false designation of origin, and unfair competition claims should be barred because elements of Nike’s sneakers are functional, there is no likelihood of confusion between the two parties’ footwear offerings, Nike’s alleged trade dress is “generic,” and Geiger’s (alleged) use of any of Nike’s marks falls within the bounds of “fair use and descriptive use.”

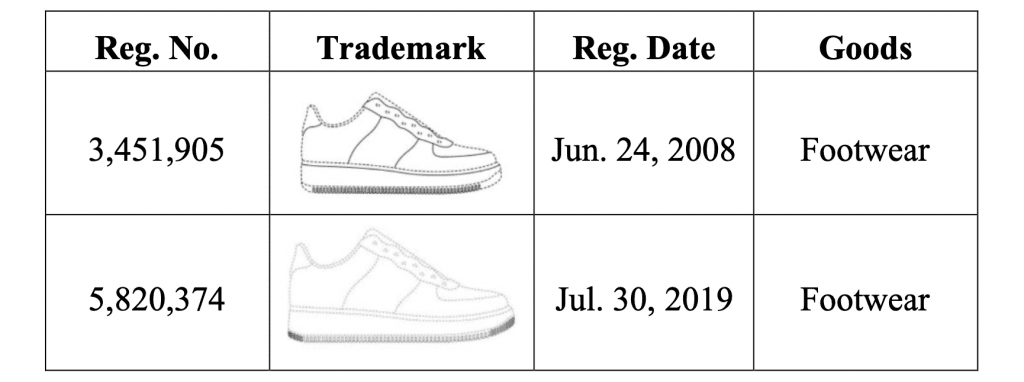

In addition to setting out defenses to Nike claims, John Geiger – which landed on the receiving end of a trademark suit from Nike as a result of its sale of sneakers that allegedly infringe Nike’s famed Dunk and AF1 trade dress – sets out claims of its own against the Swoosh. Pointing to the “actual controversy” that exists between it and Nike “regarding whether the GF-01s embody the purported trade dress depicted in” Nike’s trademark registrations for elements of the AF1 sneaker (3,451,905 and 5,820,374), and thus, whether its marketing or sale of its GF-01s has infringed Nike’s rights in its AF1 trade dress, Geiger is seeking a judgment from the court that Nike’s registrations are invalid as a matter of law and thus, should be cancelled.

(The 3,451,905 registration extends to a mark that consists of “the design of the stitching on the exterior of the shoe, the design of the material panels that form the exterior body of the shoe, the design of the wavy panel on top of the shoe that encompasses the eyelets for the shoe laces, the design of the vertical ridge pattern on the sides of the sole of the shoe, and the relative position of these elements to each other.” Registration no. 5,820,374 covers a “3D configuration comprising the design of the vertical ridge pattern on the sides of the sole of the shoe, the repeating star pattern on the toe and heel of the sole of the shoe, and the relative position of these elements to each other.”)

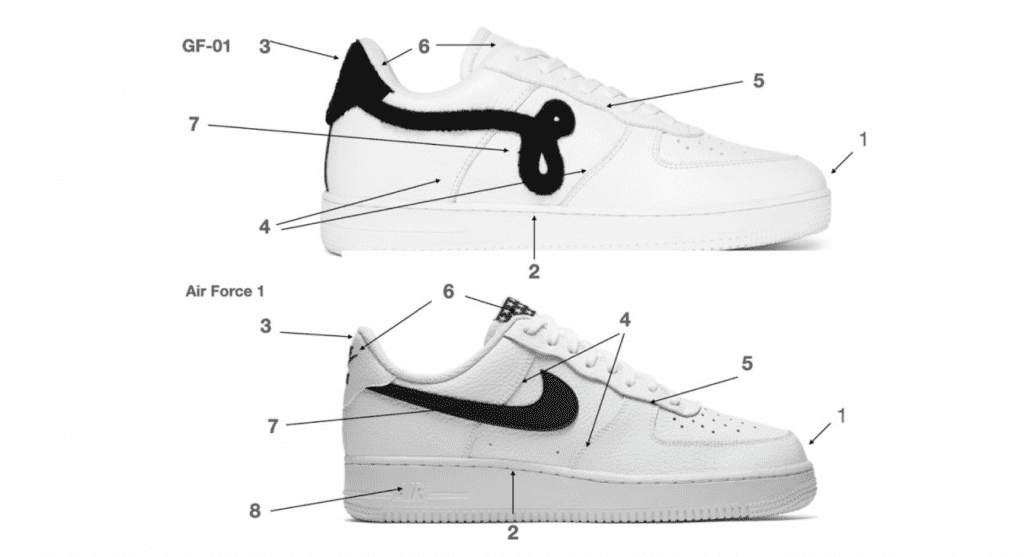

Setting the stage for its declaratory judgment claims, John Geiger asserts that in 2020, it released the GF-01 sneaker, which it has manufactured using “different proportions and features” than Nike’s AF1 – from the lower toe box and shorter midsole height to the “unique and proprietary” rubber sole. Beyond that, the GF-01 is “constructed using premium leather,” which is it is “more luxurious than the materials Nike uses,” per Geiger, and as a result, exists at “a higher [base] price point than the [AF1].” Moreover, Geiger asserts that its sneaker does not make use of any Nike branding, and instead, contains Geiger’s own branding, including its “distinct and registered trademark JG pattern logo.”

Still yet, “the GF-01 has distinct premium packaging that looks nothing like the packaging and branding that comes with the typical [AF1],” according to Geiger. The channels of distribution for the two parties’ footwear further distinguishes them, Geiger argues, stating that the GF-01 is “available exclusively on johngeiger.com and in select premium retailers and positioned next to other luxury brand footwear,” whereas Nike’s AF1 is “typically … not sold in these retailers and would not be positioned next to Geiger’s luxury products.” And finally, “The differences in proportions and features between the GF-01 and the [AF1] are obvious to any reasonable consumer,” Geiger asserts, arguing that the AF1 “has many structural features that the GF-01 does not have, including the swoosh logo, making the likelihood of confusion” – the critical element in a trademark infringement claim – “virtually non-existent.”

Aside from arguing for non-infringement based on alleged differences between its sneakers and Nike’s, Geiger more fundamentally attempts to chip away at the strength of the trademarks upon which Nike has made its case by claiming that Nike’s AF1 trade dress is generic (and therefore, incapable of indicating a single source), and functional, which is a bar to trademark protection. On the functionality front, Geiger argues that the “shoe tread, the eyelet panel, the side panel stitching, and the bottom ridges of the [AF1] shoe sole” – which are covered by the Nike registrations at issue – are “essential to the use and purpose of the sneaker and/or affect the cost, quality, performance, durability, and safety of the sneaker.”

(It is worth noting that Geiger previously argued in a motion to dismiss that the AF1 trade dress “encompasses functional elements” – and thus, cannot serve as a trademark – “because each of the elements are functional.” Geiger also claimed that the sneakers are incapable of indicating a single source without a prominently-placed Swoosh on the side. Unpersuaded, the court held that Nike showed that despite Geiger’s claim to the contrary, “the presence of the Swoosh mark on AF1 shoes does not defeat [its] allegations” that the configuration of the AF1 enjoys secondary meaning, which enables the configuration to function as a trademark. In its amended complaint, Nike pointed to its “marketing of the AF1 shoes, the extensive sales of these shoes, and the recognition these shoes garner in the broader community,” which the court determined are “enough facts to make … the secondary meaning element ‘plausible on its face.’”)

Geiger also claims that Nike has failed to police unauthorized uses of its AF1 marks, thereby causing them “to cease functioning as a symbol of quality and a controlled source.” According to Geiger, “Nike’s failure to police and failure to exercise adequate quality control has resulted in abandonment of any rights in the purported trade dress.”

Specifically, Geiger contends that “Nike has done almost nothing to police or protect the [trademark-protected AF1 configuration] from other companies that have manufactured and marketed sneakers that are nearly identical to the [AF1s].” The most prominent example cited by Geiger is the Bapesta sneaker that Japanese brand A Bathing Ape released in 2002. Despite being “identical to the [AF1], except a shooting star replaces the Swoosh design on the side of the upper, and the word BAPE replaces the word AIR on the midsole,” and “incorporat[ing] many, if not all, the trade dress elements claimed in [Nike’s registrations],” Geiger alleges that “Nike has never claimed that the Bapesta infringes upon” its rights in the AF1 marks.

On a policy note, Geiger asserts that “invalid trademarks,” which it argues is what Nike’s two registrations consist of, “unlawfully stifle the competitive and free markets.” In the case at hand, Geiger claims that “Nike has used its invalid trade dress registrations to intimidate designers and manufacturers who fear Nike’s litigiousness and do not have the resources to adequately defend themselves or pursue similar cancellation actions.”

With the foregoing in mind, Geiger has asked the court to declare that Nike’s 3,451,905 and 5,820,374 registrations are invalid as a matter of law, and to order that they be cancelled by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

John Geiger’s filing comes almost six months after Nike added it as a defendant to an ongoing case that it had previously filed against footwear manufacturer La La Land in January 2021, alleging that Geiger has taken “systematic steps in an attempt to falsely associate [its] infringing products with Nike,” and has “attempted to capitalize on Nike’s valuable reputation and customer goodwill” by using its Dunk and AF1 trade dress, as well as its iconic swoosh logo, “in a manner that is likely to cause consumers and potential customers to believe that the infringing products are associated with Nike, when they are not.”

The case is Nike, Inc. v. La La Land Production & Design, Inc., 2:21-cv-00443 (C.D. Cal.)