Before the first model even stepped onto the marathon-length, rainbow-ombre Louis Vuitton runway on a sunny day in Paris last June to commence the most anticipated show of the season, Virgil Abloh was already being accused of “copying.” The white ceramic-link chains that the 38-year old designer teased ahead of his debut for the world’s most valuable luxury brand looked a bit too much like ones previously put forth by Tanaya Henry’s highly-followed Los Angeles-based jewelry brand, per social media commentators. Just days prior, hordes of Instagram users began flooding Abloh’s account to point out the similarities.

Those same social media users were also quick to note that this was hardly the first time that Mr. Abloh had taken a bit too much “inspiration” from another designer, thereby making this part of a larger conversation, one that has compared the similarity of Abloh’s offerings from his own label Off-White to those of Raf Simons, Pyer Moss, Gramm, Colrs, Lucio Fontana, Onkler, ANREALAGE, Prada, Calvin Klein, Phillip Lim, Elisa Van Joolen, Helly Hansen, Balenciaga, New Models, and Nike, among others.

These are some of the names that have been linked to the designs of the Off-White creative director and now Louis Vuitton menswear director in recent seasons, and not in a collaborative way, but in an “endless appropriation” – as Garage Magazine put it – kind of way.

Fast forward to the Fall/Winter 2019 menswear shows and Abloh’s Off-White offerings, which were shown last week in Paris, were spotlighted – right on schedule – for their repetitive roots. The set and no small number of the garments were a take on the work of Raf Simons, social media users declared. That show-stopping yellow graffiti-covered and graphic-printed rainwear was a direct replication of previously-released designs from Punk Zec and his label Colrs.

Colrs Fall/Winter 2018 (left & center) and Off-White Fall/Winter 2019 (right)

Colrs Fall/Winter 2018 (left & center) and Off-White Fall/Winter 2019 (right)

Look closer at that same Off-White rainwear, as well as other garments from the collection, and you will see that certain elements of a logo were replicated, as well. The “OFF” written in green and surrounded by diagonally-positioned circles is something of a dead-ringer for the one that budding Manchester-based brand Gramm has been using on its garments, accessories, and packaging for several years.

If there is, in fact, a pattern to be garnered here, the same will hold true next season: garments with lookalike elements will go down the runway and furor will erupt online centering on the argument that while fashion designers are inherently indebted to creations that have come before (and should be able to freely look to others for inspiration), Abloh routinely takes it a bit too far and uses others’ design elements – maybe even protectable ones – on a whim.

This is part of the status quo that is the boundary-pushing, industry-disrupting Virgil Abloh and his wildly in-demand brand Off-White – the latter of which was named “the hottest on the planet” late last year by fashion search site Lyst. Yes, Abloh, rather notoriously, “rejects the who-did-it-first mentality of previous generations in favor of the copy-paste logic of the Internet and its inhabitants,” in the words of 032c. Yes, in his own words: conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp, who helped to pioneer the craft of the readymade, is “my lawyer,” a reference to the late artist’s practice of taking already-existing elements and elevating them as art.

In reality, though, the late Duchamp isn’t Abloh’s counsel. He has a New York law firm on retainer.

Gramm’s logo (left) & Off-White (right)

Gramm’s logo (left) & Off-White (right)

In addition to his position as a youth-centric cash cow of epic proportions, 032c asserts that Abloh’s “new order” – i.e., his way of working, which sees him “absorb pre-existing intellectual property into his reference system” – is “protected by a fortress of irony.” The Berlin-based magazine pointed to Abloh’s frequent use of quotation marks on everything from puffer jackets to shoe laces as an example of “one of the many tools that Abloh uses to operate in a mode of ironic detachment.”

But the big irony here goes beyond printed shoe laces. The irony is that against the background of all of these “references” that people inevitably find in Virgil’s collections (some – although certainly not all – of which could, in theory, give rise to claims of infringement either of the copyright or trademark kind), both his brand and Louis Vuitton rely heavily on legal protections to prevent others from taking too much from their own works.

It is not difficult to garner from its trademark filings, at least, that Off-White has a strategy in place to formally acquire and protect its intellectual property rights. For instance, the brand currently maintains at least 14 trademark registrations with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, with another 50 or so applications pending, and has initiated at least 5 trademark-centric lawsuits over the past couple of years. Yet, it does not necessarily seem to me that the same approach to intellectual property protection and enforcement is reflected when say, a logo that shares marked – and maybe even confusing (given Abloh’s penchant for collaboration) – similarities with Gramm’s pre-existing logo finds its way onto garments in the Off-White Fall/Winter collection.

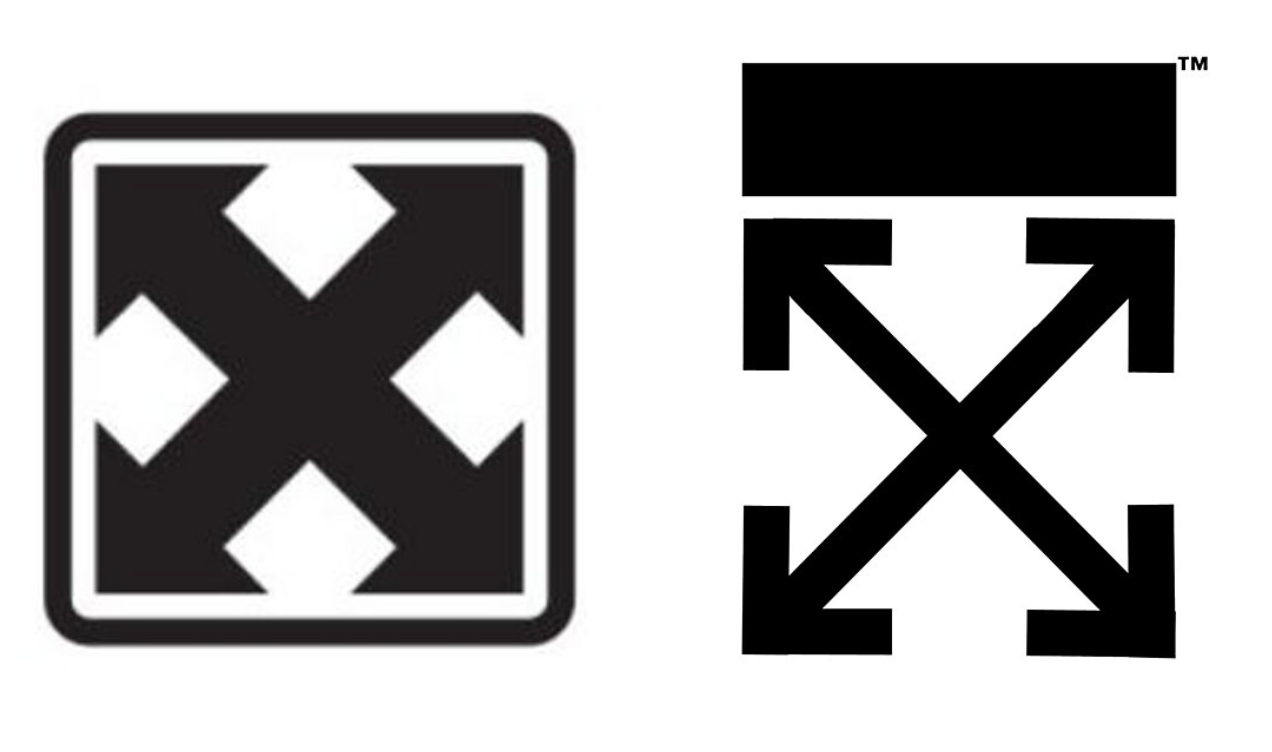

H-Street’s logo (left) & one of Off-White’s logos (right)

H-Street’s logo (left) & one of Off-White’s logos (right)

This is not to say that brands, such as Off-White, should not seek legal protections for their names, logos, and protectable design signatures; they should. It is a savvy business and legal move, particularly since the upper echelons of the fashion industry and even the burgeoning streetwear segment depends largely on the appeal of brand names and logos.

This is also not to fault Abloh for having his legal team enforce the rights that he does maintain; they should, certainly from a trademark perspective, since trademark law requires that a rights holder police unauthorized uses of his/her mark to prevent consumer confusion and/or dilution of the trademarks, even if those trademarks are a bunch of diagonal lines; a red zip-tie hangtag, as seen attached to Abloh’s popular Nike sneakers; and arrows, the latter of which H-Street skateboards has been using since its founding in 1986.

Still yet, there is no denying Abloh’s prowess in the modern market, but it is also difficult not to notice what appears to be a potential disconnect between his treatment of his own designs and those of others, and the irony that comes with it. Even Vetements’ Demna Gvasalia, who was verbally slaughtered in a recently-settled lawsuit for his continued “willingness to copy the work of others,” has the sense not to ask his counsel to put his name a lawsuit when people play on his brand’s name.