The Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) has given the green-light to a proposal from Nasdaq that will refashion the public disclosure requirements for companies listed on the stock exchange. According to the New York-based stock exchange, the aim of the proposal – which was first introduced in early December 2020 and was given SEC approval on August 6 – is to “provide stakeholders with a better understanding of [a] company’s current board composition and enhance investor confidence that all listed companies are considering diversity in the context of selecting directors.”

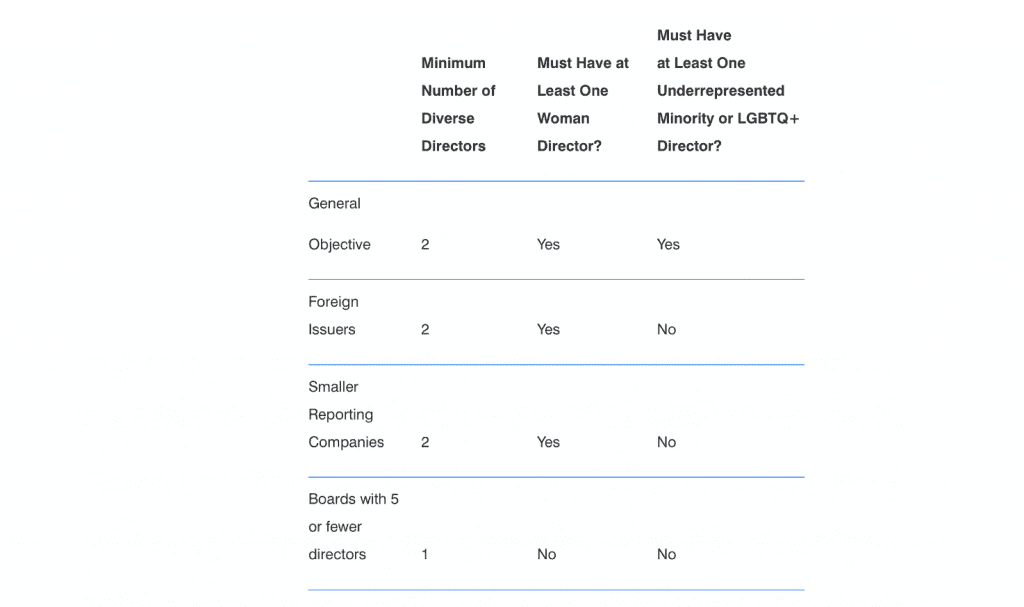

The since-approved proposal that Nasdaq first presented to the SEC last year requires that all Nasdaq-listed companies publicly disclose board-level diversity statistics via Nasdaq’s proposed disclosure framework within one year of the SEC’s approval of the rule. Rule 5605(f) generally requires companies listed on Nasdaq’s U.S. exchange to have at least two diverse directors, including: one self-identified woman director, and one director, who self-identifies as an underrepresented minority – which Nasdaq defines as “Black or African American, Hispanic or Latinx, Asian, Native American or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander or Two or More Races or Ethnicities” – or as LGBTQ+.

If a company does not satisfy both of these criteria, the company must: (1) specify the particular aspects of board diversity it fails to satisfy; and (2) provide the reasons why it does not have two diverse directors. Such disclosure must be provided in advance of a company’s next annual meeting of shareholders in its proxy or information statement (or Form 10-K or 20-F, if it does not file a proxy) or on its website.

Since its introduction, Nasdaq’s proposal has been the subject of mixed responses. Counsel for the stock exchange alerted the SEC in a letter on February 5 that 86 percent of the 162 substantive comment letters filed in connection with the proposal supported the adoption of the new rules, which aim to make up for a large-scale lack self-reporting by publicly-traded companies when it comes to diversity figures for C-suite executives and board members. Yet, not all interested parties were in board, with twelve Republican Senators on the U.S. Senate Banking Committee, for instance, submitting a letter to the SEC in February, urging the securities regulator to shoot down Nasdaq’s proposal on the basis that it would “interfere with boards’ duties to their shareholders, violate securities disclosure principles and could impose costs on companies.”

In response to pushback, Nasdaq submitted a revised proposal in which it amended some of its previously set-out points. Among other things, the amended version proposed that companies with smaller boards (i.e., those with five or fewer directors – would need to include one diverse director, instead of the previously proposed two. Another change allows for extra time for newly-listed companies to become complaint with the diversity rules; they would have an additional two-year period after the phase-in period to fully meet the diversity objective.

Meanwhile, Nasdaq added a one-year grace period in the event a vacancy on the board brings a company under the recommended diversity objective.

An SEC Split

Reflecting on the approval of the Nasdaq proposal, SEC Chairman Gary Gensler said in a statement last week, “These rules will allow investors to gain a better understanding of Nasdaq-listed companies’ approach to board diversity, while ensuring that those companies have the flexibility to make decisions that best serve their shareholders.” Not all of the SEC’s commissioners were on board, of course, with Commissioner Hester Peirce (R) voting against the proposal, and Commissioner Elad Roisman (R) issuing a partial dissent, in which he anticipated future legal issues being born from the new rule given the SEC’s role as the “adjudicating body for exchange delisting decisions.” One of Roisman’s “serious concerns” on this front stems from the fact that “the SEC – without any doubt, a state actor – may need to take future action in which the agency must consider disclosure of the racial, ethnic, gender, or LGTBQ+ status of individual directors.”

More broadly, the 3-2 split on the SEC “reflects a broad and deepening divide concerning recent SEC moves in the ESG space, including disclosures related to climate risk,” Mintz stated in a client note this week. “The significant dissent among the SEC commissioners suggests that there will be substantial opposition to any new disclosure requirements focusing on ESG, and that efforts may be made by the regulated industries to delay any rule-making in the expectation of a different political balance on the SEC within a few years.”

Additional rule-making is, nonetheless, expected in light of increasing demand for board diversity and related disclosures, paired with a larger push for attention to ESG issues more generally and uniform reporting by publicly-traded entities on this front.

As for timing of the newly-approval Nasdaq rule, the stock exchange states in its proposal that the diversity disclosure mandates will come into effect on the later of “one calendar year from the date of SEC approval of the revised proposal” or … “the date the proxy statement is filed for a company’s annual meeting during the calendar year of such SEC approval date.”

A Larger Push

Nasdaq’s proposed requirements are the first of their kind, but the push for corporate diversity has found favor among lawmakers in states like California, Illinois, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania, which have enacted laws governing board diversity for publicly traded companies. In September, California Governor Gavin Newsom, for instance, signed into law AB 979, thereby, requiring that by the end of 2021, California-headquartered public companies have at least one director on their boards that is from an “underrepresented community.” Before that, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker implemented Public Act 101-0589 in August 2019, requiring that publicly-traded domestic and foreign corporations with principal executive offices in Illinois make additional reportings to the Secretary of State about the makeup of their executive directors and boards, as well as about their policies and practices for promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion, among other things.

Meanwhile, “Some of the world’s biggest investors,” such as BlackRock Inc., Vanguard Group Inc. and State Street Global Advisors Inc. “have threatened to pull their money out of companies that do not show progress on certain environmental, social and governance issues, such as board diversity,” according to S&P Global. And at the same time, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. announced in June 2020 that it would stop underwriting IPOs for companies in the U.S. – and Europe – that do not have at least one diverse director. Such U.S.-specific activity follows from efforts – and in some cases, legislation – in Europe. Lawmakers in France, for example, passed a quota law of 2011 to order to increase gender representation on the boards of the country’s largest firms.