Statements from H&M and Nike, among other Western brands, expressing “concern” about working conditions in China’s Xinjiang region prompted widespread backlash against the retail giants beginning in March. Burberry, Zara, adidas, and Uniqlo also found themselves on the receiving end of similar boycotts amid rising attention to claims of forced labor in Xinjiang, which is home to detention camps where ethnic Uighurs and other Muslim minorities are reportedly forced to “learn Chinese and memorize propaganda songs” and to work as part of a sweeping “re-education” campaign, putting non-native brands in a position of essentially having to choose between speaking out about such documented human rights issues and cutting ties, as a result, and maintaining the status quo with consumers in the lucrative Chinese market.

As the New York Times reported in early April, “Calls for the cancellation of H&M and other Western brands went out across Chinese social media as human rights campaigns collided with cotton sourcing and political gamesmanship.” Chinese netizens “react[ed] with fury” to a number of major multi-national retail brands distancing themselves from suppliers in Xinjiang, a region that is responsible for 20 percent of the global cotton supply, and argued that the allegations – and brands’ responses to them – “are an offense to the [Chinese] state.” In addition to losing their Chinese ambassadors, many of whom pulled out of contracts due to companies’ public stances against Xinjiang supplier abuses, companies like H&M were “wiped off China’s leading e-commerce, ride-hailing, daily-deals and map applications” in the wake of year-old statements that started recirculating in early 2021 amid a larger sanctions battle with the U.S., European Union, Britain and Canada on one side and China on the other, the Wall Street Journal revealed.

With the dust starting to settle from the height of consumer rage in late March, how are brands faring? Has the cancel-culture moment put a significant dent in brands’ operations? The results appear to be mixed.

Puma, for one, stated that it expects that the Chinese boycotts, paired with “congestion at ports [will] hit its sales,” despite giving “an upbeat outlook for 2021 following a strong first quarter,” according to Reuters. “We can still see that trend is continuing,” Puma CEO Bjorn Gulden stated in late April, reflecting on the fallout from consumer pushback in China. “There is less activity in the Western brand stores than there would have been if tension wasn’t there.”

This week, Bloomberg stated that online sales for the likes of adidas, Nike, and Fast Retailing-owned Uniqlo “plunged in China” in the wake of the backlash, with sales on adidas’s Alibaba-hosted Tmall shop “slumping by 78 percent in April” compared to April 2020, according to Morningstar Inc. Nike’s sales were similarly down – albeit by a lesser 59 percent, and still yet, sales for Uniqlo, another brand that found itself in the crosshairs of consumer boycotts, “dropped by more than 20 percent.” Despite such striking effects, Morningstar analyst Ivan Su told Bloomberg that the boycott behavior against brands is “most likely temporary,” and “should most likely fade over the next months.”

While sales are slated to return to normal levels, adidas may not be off the hook just yet, and there is speculation that the headline-making pushback will directly affect its sale of Reebok, which went up for auction on Wednesday. Reuters expects the German sportswear giant to receive a number of bids for the American brand, which could go for an estimated $1.2 billion. The auction “risks being affected by a political row over possible forced labor in China’s western Xinjiang region,” though, the publication asserted, citing three unnamed sources.

Meanwhile, not all brands have suffered equally. Hugo Boss lost a number of its famous Chinese ambassadors and drew scorn from consumers on social media in connection with its stance on the issues on the Xinjiang region. However, according to Yahoo Finance, the company reported first-quarter sales that were “almost double in mainland China” on a year-over-year basis, with CEO Yves Mueller said that he “expects that momentum to continue unchanged despite the boycott calls.”

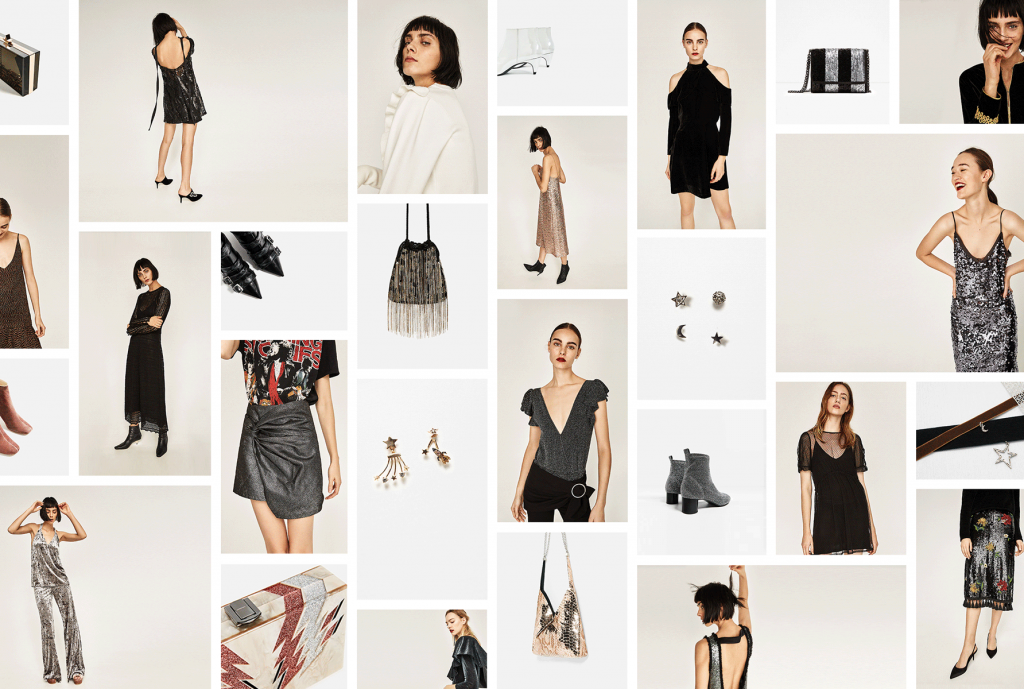

Finally, a number of companies have not only faced consumer pushback, they have landed on wrong side of litigation. According to a complaint that was filed with the Paris Prosecutor Office on April 12, French legal association Sherpa, human rights NGO Collectif Ethique sur l’étiquette, the Uyghur Institute of Europe and an individual Uyghur victim claim that based on publicly available information, “a large number of brands and distributors in the fashion sector” – specifically, Uniqlo, Zara’s parent company Inditex, Skechers USA Inc. and French apparel group SMCP, the owner of the Sandro and Maje labels – maintain ties to suppliers in the region, and as a result, “may be involved in the forced labor imposed on the Uyghur population.”

Sherpa asserts that despite the publications of reports from various researchers and media outlets since 2019 that “highlight the existence of systematized forced labor in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region by the Chinese government,” Uniqlo, Inditex, Skechers, and SMCP have “continue[d] to subcontract part of their production or to market goods using cotton produced in the region, and thus, [are] knowingly taking advantage in their value chain of the workforce in a region where crime against humanity are being perpetrated.”

The retail companies’ alleged failure to sever their relationships with suppliers linked to Xinjiang “exposes the impunity of transnational corporations that profit from these crimes through their modus operandi and business model,” Sherpa argues, noting that its newly-filed complaint is merely “the first of a series of filings organized by the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights that will be filed in the coming months in other European countries.”