Counsel for Nicolas Ghesquière and Balenciaga were present in a Paris civil court in July 2014 for oral arguments in connection with the breach of contract case that Balenciaga filed against its former creative director of fifteen years. (The parties have since agreed to attempt to mediate the matter outside of court.) In its lawsuit, the Paris-based design house alleges that Ghesquière, who was succeeded at the Kering-owned company by Alexander Wang and now serves as creative director for Louis Vuitton, breached his separation agreement with the house. That agreement mandated that Ghesquière would “refrain from making declarations that could hurt the image of Balenciaga or its parent company, Kering.”

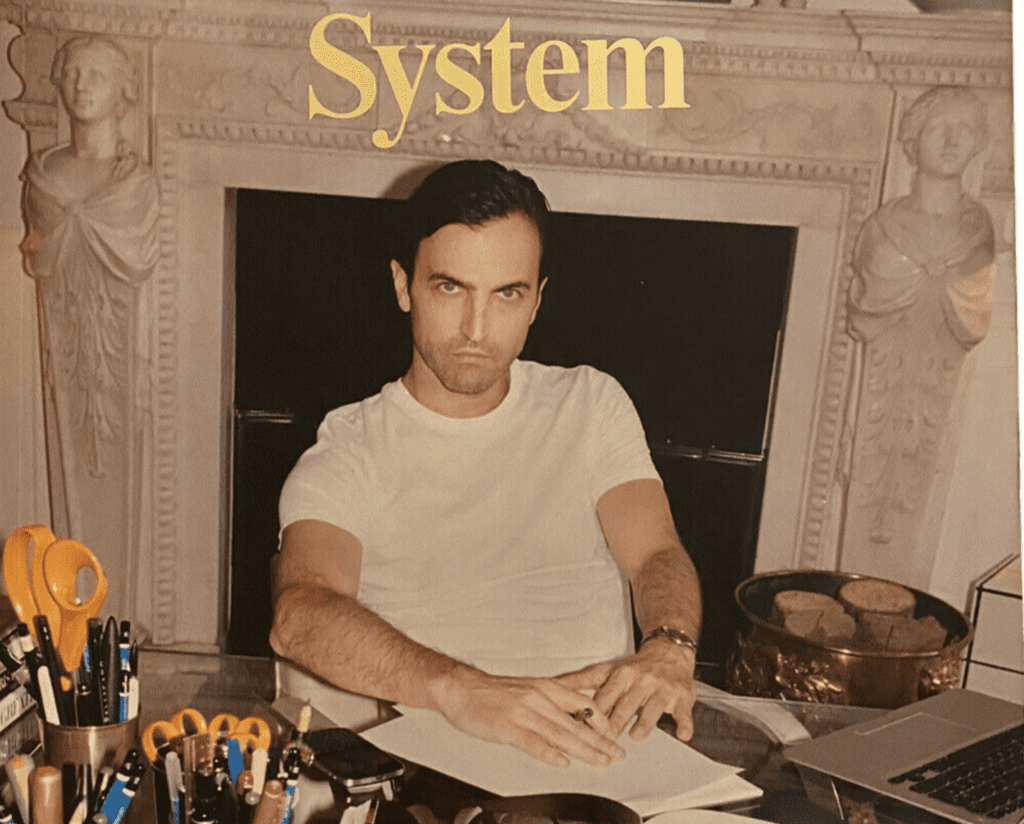

The statements at issue stem from a two-part interview between Ghesquière, who left his role at Balenciaga in November 2012, and stylist Marie-Amélie Sauvé that took place in December 2012 and January 2013, and that ran in System, a bi-annual publication. In connection with his departure, Balenciaga reportedly paid Ghesquière “6.6 million euros, or $8.7 million at current exchange, as compensation for breaking his latest employment contracts with [the brand in November 2012], signed in 2010 and 2012.” Ghesquière also reportedly “walked away with 32 million euros, or $42.3 million, for the purchase of his 10 percent stake in the company, granted to him when then-parent Gucci Group bought Balenciaga in 2001.”)

In one of the most highly contested excerpts, Ghesquière said of Balenciaga …

“They wanted to open up a load of stores but in really mediocre spaces, where people didn’t know the brand. It was a strategy that I just couldn’t relate to … And it was around that time that I heard people saying, ‘Your style is Balenciaga now, it’s not your style anymore, it’s Balenciaga’s style.’ That’s what I mean by the dehumanisation. Everything became an asset for the brand, trying to make it ever more corporate – it was all about branding. I don’t have anything against that; actually, the thing that I’m most proud of is that it’s become a big financial entity and will continue to exist. But I began to feel as though I was being sucked dry, like they wanted to steal my identity while trying to homogenise things. It just wasn’t fulfilling anymore.”

What followed was a lawsuit, filed in June 2013, in connection with which Balenciaga sought $9.5 million in damages to remedy the reputational harm it alleged to have experienced as a result of Ghesquière’s comments. The closely-followed lawsuit has posed an array of interesting questions, including the permissible scope of such separation agreements. Perhaps, though, the most pressing issue here is not actually derived from legal principles at all: Mr. Ghesquière’s counsel, Michel Laval of Michel Laval & Associés, argued in court in July 2014 that his client did not intend to besmirch his former employer. Instead, Laval told the Tribunal de Grande Instance that Ghesquière was voicing a sentiment that many individuals in his position certainly share. Specifically, Laval stated: ”This is the old and difficult question of the relationship between the creator and the fashion house. The creator regrets that business logic prevails … it is a characteristic of the designer that gets lost in creation.”

Not a novel claim, Laval’s argument – namely, that Ghesquière was reflecting on the significant amount of strain placed on modern-day designers and creative directors – is one that has reverberated in the industry over the past several years, in particular. For instance, in 2013, Suzy Menkes, then-style editor of the International New York Times, addressed the “new speed of fashion.” She said that the current cycle, one that has big-name creative directors (a la Karl Lagerfeld) turning out roughly eight collections a year, with as many as ten runway shows, and smaller labels creating at least four, many of which are not limited to garments but also include accessories and which encompass not one but both genders, is “simply mad.” At the same time, Menkes suggested that “the pace of fashion today [may have been] part of the problem behind the decline of John Galliano, the demise of Alexander McQueen and the cause of other well-known rehab cleanups.”

Around the same time, French designer Pierre Cardin, commented on the influx of designers and the unsustainable pace at which fashion moves, suggesting that it is virtually impossible to create lasting fashion, or “fashion for tomorrow,” as he put it, every six months or so.