Insolvency is stalking many businesses in the United Kingdom (and beyond) in the wake of COVID-19 and Brexit. This has been particularly visible in retail, with 2021 already seeing stationery chain Paperchase in administration and former high-street leaders Debenhams and Topshop being mopped up by online upstarts Boohoo and ASOS. Meanwhile, pubs and restaurants are lobbying hard to be allowed to open sooner rather than later, while Chancellor Rishi Sunak is signaling that the March budget will give more support to businesses and workers.

But when the support measures finally stop, experts expect an insolvency tsunami. According to a recent Begbies Traynor Group report, the number of UK businesses in “significant distress” rose 27 percent year-over-year in the final quarter of 2020 to 630,000, with increases across all sectors. Business collapses will obviously be painful for a lot of people involved, but as a result of the law that governs insolvency in the UK, some stakeholders in these companies will come out a lot worse than others.

The battle for priority

Perhaps the best example of the imbalance in insolvencies is in the world of football. Nearly half of clubs in top four tiers of the English leagues have gone through an insolvency since 1992. When a club enters administration, for example, the “football creditor rule” kicks in. This gives certain creditors priority status in getting their money back, including players, clubs and the football league authorities.

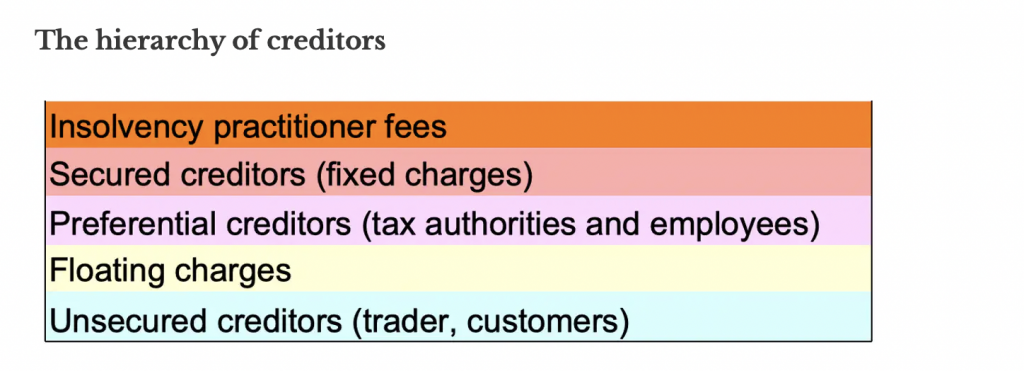

It can lead to perverse outcomes: for instance, a multi-millionaire footballer might get paid ahead of a cleaner who is paid by an outside cleaning company that is owed money by the club. League authorities maintain that this rule exists for the financial integrity of the league, but it clearly creates losers, too. In the insolvency world, this is known as the “waterfall” because value trickles down a pre-determined hierarchy of all the groups of creditors. Jockeying for position is the name of the game.

Once insolvency practitioners have been paid, the law prioritizes “secured creditors” over all others. These are creditors who have lent money in exchange for collateral – usually in the form of a mortgage over property or plant or machinery. These are known as fixed charges, and these creditors will normally be banks. They have maneuvered into this priority position in the hierarchy over many decades.

Next comes “preferential creditors,” whose status has been granted by parliament. This includes employees, who can claim outstanding holiday pay and some unpaid wages. And very controversially, tax authorities were also recently re-added to the list of preferential creditors after an absence of two decades.

After preferential creditors comes another type of bank lending in exchange for collateral, known as floating charges. These loans are secured against things like stock and raw materials, but could include any asset. Last comes “unsecured creditors,” which refers to the likes of customers and suppliers. This could be a customer who ordered a coat that is being custom-made, or suppliers that sell textiles to a fashion brand.

Some unsecured creditors do manage to increase what they can recover in insolvencies. Some suppliers, for example, take out credit insurance. Others cleverly use contractual provisions that mean that they continue to own goods until their customer pays for them.

Meanwhile, some customers that have become creditors of failed companies have been protected by the law of trusts in the past. This means that the money they use to purchase a sofa, or a Christmas basket, is specially reserved for them in a dedicated bank account. Those funds go straight back to the consumers, bypassing the insolvency process. We have seen this with Christmas savings clubs and some home-furnishing companies.

The crumbs

Various studies have shown that unsecured creditors get lamentably little in an insolvency situation. Forty years ago, the emeritus Oxford law professor Roy Goode questioned whether the law was too favorable to secured creditors, and as far back as 1897 Lord Macnaghten, one of the most senior judges of the era, expressed “some sympathy for unsecured creditors.” That sympathy was well placed, then and now – particularly in view of coronavirus and Brexit. This is despite numerous attempts to improve their lot, such as the “prescribed part” rules.

These entitle unsecured creditors to a small proportion of whatever the floating-charge creditors are able to extract from an insolvency process – though it only applies to floating charges agreed from September 15, 2003, which leaves quite a large proportion of them.

Should the system be reformed? This depends on your position in the waterfall. Banks would say their priority ranking is necessary to allow them to provide the lending required for economic growth. Tax authorities and employees would also say they deserve their preferential treatment as they did not become creditors by choice. Unsecured creditors would probably say we need to do more to help them. The relevant legislation around the “prescribed part” was recently amended to increase the portion of value in each insolvency reserved just for these creditors. This was a step in the right direction, and it could be further reformed in certain ways to give these creditors a slightly greater share of the pie, including extending the entitlement to floating charges pre-2003.

To help these creditors more than that, business associations such as the Institute of Directors could take more responsibility for educating smaller businesses about the ways in which some haul themselves up the hierarchy by using contractual provisions over who owns the goods they supply. These businesses might also protect themselves in the same way as Christmas clubs by requiring the customers they supply to ring-fence the money they owe before it is settled.

These solutions may not be perfect, but as ways of improving the bargaining position of unsecured creditors, they are worth considering.

John Tribe is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Liverpool. (This article was initially published by The Conversation)