In October, Comme des Garçons was named in an ugly lawsuit, in which a former HR employee accuses the famed fashion company of engaging in a scheme of visa fraud, labor violations, and retaliation. The suit, which appeared as though it would end in a quick – and quiet – default judgment after CdG failed to respond to the complaint in a timely manner, has since resurfaced, with the 52-year old fashion company arguing that it was not immediately aware of the case filed against it, and thus, the court should revive the matter so that it can defend itself against the striking claims that it has routinely violated “minimum wage, overtime, medical leave, and immigration laws.”

The matter allegedly got its start in February 2019 when plaintiff Jenifer Mejia says that she was hired “under the pretense” that CdG, which owns the Comme des Garçons brand, as well as the Dover Street Market retail chain, wanted to “create a legitimate HR department for its U.S. offices.” Ms. Mejia asserts that things swiftly went south, and before long, she “was treated as a thorn in the company’s side for her opposition to [CdG’s] illegal treatment of company employees, and then fired purportedly over a few dollars-worth of office supplies.”

According to the complaint that she filed in a New York federal court in October 2020, Mejia alleges that issues began to arise within days of the start of her 5-month tenure for the Rei Kawakubo-founded fashion group. On the second day of her employment as CdG’s Human Resources Generalist, for instance, she claims that the company’s Chief Financial Officer Elaine Beuther “directed [her] to whiteout, re-date, and forge the signatures of two employees on New York State Paid Family Leave insurance forms.”

And things only went downhill from there, she asserts.

“An Emerging Pattern”

As her employment carried on, Mejia alleges that she began to witness instances that were part of “an emerging pattern of CdG failing to pay [certain] wages,” and only remedying such alleged failures “when the affected employees complained that they had not been paid.” For instance, she claims that she was made privy to complaints from individuals who worked in CdG-owned Dover Street Market stores in New York and Los Angeles that they had not been paid, and alleges that she was “alarmed at the volume of employees requesting backpay.”

On another occasion in March 2019, Mejia says that she discovered that CdG had a “ghost employee” in the Digital Coordinator of the Press Department role. She claims that CdG was “missing employee paperwork (such as an I-9, W-4, Offer Letter, or Employment Agreement)” for this individual, and yet, it was paying this employee $47,500, which was “below the newly-raised salary threshold for white collar exemptions to overtime under the New York Labor Law.”

When she brought this issue to Beuther’s attention, Mejia claims that “Beuther looked surprised and uncomfortable, and then retorted in a threatening tone that she had been doing HR for this company for 20 years, and if there were labor updates she would be advised by the company’s lawyer or she would ask the company’s lawyer personally.”

Still yet, around the same time, Mejia claims that she was informed by the Los Angeles store manager that “a number of employees … were still not being paid minimum wage 5+ months after a statewide increase had gone into effect.” Mejia says that when she “raised [the issue] that the company was 5+ months out of compliance … Beuther became visibly angry, shaky, and rushed out that that this wasn’t Ms. Mejia’s concern.”

In furtherance of CdG’s pattern of allegedly failing to comply with an array of federal and state laws, Mejia alleges that on another occasion in late March 2019, “a terminally ill sales associate by the name of Jennie requested a month off for medical treatment.” Because CdG “does not provide paid sick leave,” Mejia asserts in her complaint that “Beuther explained to [her] that Jennie had already used her company-allotted 17 days of all-purpose [paid time off],” and “continued that Jennie should just quit if she wasn’t going to work, but that they couldn’t fire her for ‘obvious reasons.’”

Mejia claims that “Beuther told [her] to simply inform Jennie that she had used all of her PTO, and explicitly instructed Ms. Mejia not to inform Jenny of her legal rights to medical leave, whether under the Family and Medical Leave Act, the New York State Paid Family Leave Law, or the New York City Paid Sick Leave Law, in the hopes that Jenny would not be aware of her rights and simply quit.” While Mejia says that she “pushed back against this illegal directive and requested that the two speak to the company lawyer, [she] was rebuffed [by Beuther], and as a result, Jennie resigned.”

And finally, in May 2019, Mejia contends that she was asked by Beuther to enter new hire paperwork into CdG’s system for an individual by the name of Selia Fragapane. The following day, Mejia claims that “Beuther told [her] that Selia Fragapane is a Canadian national on a TN-1 Visa, and that her status would ‘require discretion.’ When Mejia met with Ms. Fragapane to complete her I-9 verification, Mejia realized her visa did not allow her to work the position she was hired for.”

When she informed Beuther of the issue, Mejia asserts that she was told “to essentially stop asking questions and to put Ms. Frangapane in the system” anyway.

(Mejia asserts that Fragapane was ultimately fired in July 2019 after she was caught on camera “physically assault[ing] a sales associate that she was in the process of terminating.” In late July, Mejia claims that “a whistleblower emailed company ownership the assault victim’s report, video, footage and police report,” and noted that “Ms. Fragapane had been reported to ICE.”)

Ultimately, Mejia says that she was also fired in July 2019 “for simply trying to do her job.” Specifically, Mejia claims that while she was officially fired for “order[ing] a few dollars’ worth of office supplies after the company deadline for submitting such orders,” the real reason for her dismissal was retaliation on the part of CdG in response to her raising “numerous labor and employment issues,” which she says were routinely met with “obfuscation and denial.”

With the foregoing in mind, Mejia has accused CdG of retaliating against her for engaging in a protected activity – i.e., alerting the company of its failure to comply with various labor and wage laws – in violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act, the False Claims Act, New York State Labor Law, and the California Labor Code. More than that, she claims that CdG ran afoul of the California Family Rights Act and the Family and Medical Leave Act by retaliating against her for opposing the company’s alleged violations of those Acts, both of which require covered employers to provide employees with job-protected leave for qualified medical and/or family reasons.

As a result of such violations, Mejia claims that she “has suffered and continues to suffer economic losses, mental anguish, pain and suffering and other damages,” and is entitled to an array of damages.

Is the Case is Back On?

Hardly a straightforward case to date, Mejia filed her complaint on October 28, 2020, and when CdG failed to respond to the case, a default judgment was entered against it on December 17, 2020. The case did not actually come to a close, however, as CdG has sought to vacate the default judgment on the basis that its “failure to respond [to Mejia’s case] was not willful.” The company asserted in its January 15 motion that it was not aware of the filing until after the default judgment was entered because its “corporate address had changed and had not yet been updated with the Secretary of State.”

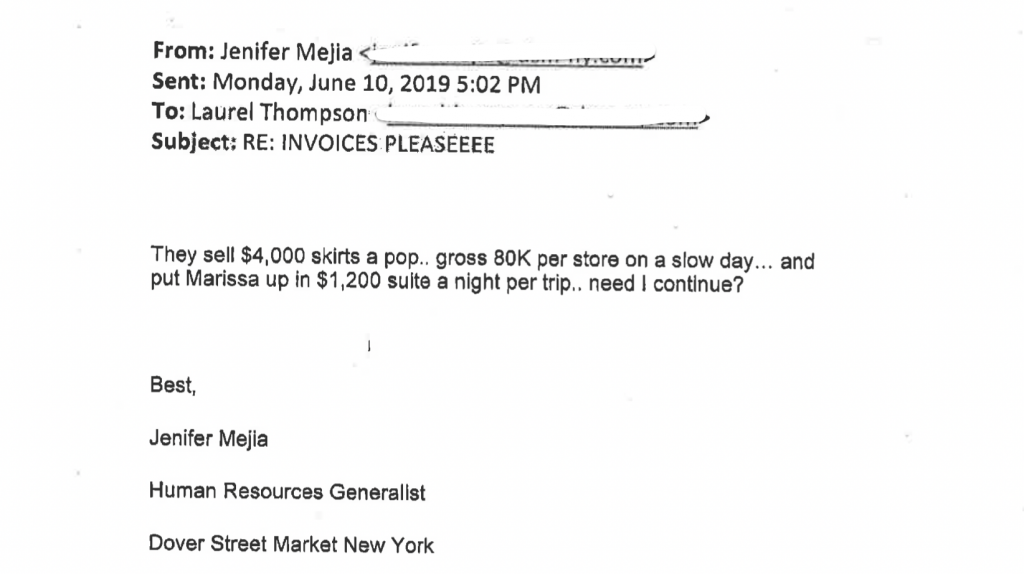

As for the merit of Mejia’s case, CdG asserts in its motion to vacate that it “had a legitimate business reason to terminate [her] employment,” namely, her failure “to meet CdG’s expectations of a Human Resource Generalist, and because she breached the trust of CdG, by engaging in inappropriate and inflammatory banter with a staff member.”

(CdG attached an email exchange between Mejia and an administrative assistant/front desk receptionist in CdG’s New York office, in which Mejia references the price of the garments sold at the Dover Street Market stores, how much the stores generate in sales, and how much the company spends on accommodations for a company buyer when traveling in connection with her request for reimbursement for office supplies).

More than that, CdG characterizes Mejia’s claim “that CdG hired [her] with the expectation that she fulfill these important HR duties in February 2019, only to terminate her five months later because she attempted to do so” as “illogical,” and asserts that “from the outset of her employment,” Mejia failed to meet the company’s expectations. Per CdG’s motion, Mejia “made mistakes and exhibited a lack of judgment that caused CdG to realize that [she] was not the seasoned Human Resources professional it expected her to be.”

In a separate but related filing, Beuther provides a declaration denying a whole host of Mejia’s assertions, stating that she “reviewed [Mejia’s] complaint and am very surprised by the allegations she makes.” According to Beuther, Mejia’s “employment was not terminated in retaliation for her efforts to ensure that CdG was compliant with minimum wage, overtime, medical leave and immigration laws,” and instead, she was fired “because she made mistakes, she failed to meet CdG’s expectations of a Human Resource Generalist, and because she breached the Company’s trust.”

Because Mejia “has not been prejudiced” by CdG’s delay in responding to her suit and will not be prejudiced if the default judgment is vacated, and because it “has meritorious defenses to [her] claims,” CdG argues that “good cause exists to vacate the default judgment.”

According to the case docket, Mejia’s opposition to CdG’s motion to vacate the default judgment, should she choose to file one, is due on February 3.

A representative for CdG told TFL on Tuesday, “The claims are baseless, and we intend to vigorously defend against them.”

*The case is Mejia v. Comme Des Garçons, Ltd., 1:20-cv-09057 (SDNY).