From the story of how World War II shortages, including those for product packaging supplies, led to the birth and larger rise of Hermès’ famous orange color trademark, and a deep dive into how the famed Christian Louboutin v. Yves Saint Laurent lawsuit saw the parties face off in court and before the court of public opinion … to an enduring legal rivalry between Nike and Skechers – complete with four lawsuits, claims of corporate “bullying,” and an alleged pattern of rampant copying – and a look at how “progressive,” millennial-focused workplaces have tried to keep employees’ discrimination claims quiet, here are several of the features we penned in 2020.

1. A Shortage of Product Packaging During WWII Led to the Birth of Hermès’ Famous Orange Color Mark

In 1942, the city of Paris was rife with shortages. While World War II would be over for the French within a couple of years, the wartime shortages were not winding down. For one company, a then-105-year-old, family-owned leather goods and apparel manufacturer named Hermès, one immediate impact of the enduring scarcity was its inability to acquire its usual product packaging. Neither the creamy beige and gold cardboard boxes nor the rich marigold-hued ones with a shade of bronze running along the corners that it had traditionally used to package its high-end offerings were accessible. The boxes that had “defined Hermès’ elegance” for decades were no longer within its reach.

As the brand’s story goes, the only packaging that was available – and offered up to Hermès by its supplier – came in a vibrant orange, “the color nobody wanted.” Given the option of adopting a bright new hue for its boxes or being left without packaging for its equestrian-centric leather goods and growing businesses of handbags and ready-to-wear, which were first incorporated into the house’s offerings in the 1920s, Hermès chose the former, and “the orange Hermès box was born.”

2. Christian Louboutin: Red Soles, High Heels, and a Global Quest for Trademark Rights

Inside a package addressed and sent to Yves Saint Laurent on an otherwise insignificant day in April 2011 was a complaint. Christian Louboutin was suing the company for more than $1 million. Within a matter of days, the media was abuzz. Christian Louboutin’s legal team had filed a trademark infringement lawsuit in a New York federal court, giving rise to what would swiftly become one of the most infamous footwear lawsuits in fashion history.

After all, on the receiving end of that complaint was not a fast fashion retailer or a frequently-sued footwear company like Steve Madden. It was a fellow luxury goods brand, and at the heart of the closely-watched lawsuit was Louboutin’s trademark-protected red sole and its allegations that by selling $800-plus red high heeled shoes that also bore a red sole, YSL was infringing its coveted federal trademark registration that Louboutin had maintained since January 2008.

3. Are Birkin Bags Really a Better Investment than Stocks and Gold? One Company is Actively Testing That Theory

Not only is Rally the first company to look to Reg. A+ to sell shares in a Birkin bag; it is arguably the first company to provide an actual basis for testing the enduring speculation that the wildly coveted Birkin bag just might fare more favorably over time than some of the more traditional classes of assets. By offering shares in the bags, Rally – and its co-founders Chris Bruno, who came from the world of venture capital, and Rob Petrozzo, whose background is in product design – is setting the stage to see just how valuable an investment these bags really are from a securities perspective.

The notion that Birkin bags are an investment that is just as attractive as – or possibly, even more attractive than – conventional financial vehicles is not exactly a novel one. In fact, the Rally offering comes four years after Baghunter, an online retailer for luxury handbags, garnered headlines when it made a striking proclamation: Hermès Birkin handbags are a better investment – on an annualized basis – than gold and the stocks in the S&P 500 index.

4. Counterfeits or Control: What is the Real Issue Between Brands and Amazon?

Many brands have sworn off Amazon for the same glaring reason: fakes. The Jeff Bezos-launched e-commerce giant was publicly taken to task in 2016 and again in 2017, for instance, when Birkenstock revealed that it would cut all ties with the company on the basis of “a series of violations of the law on the [Amazon] Marketplace platform.” According to Birkenstock, those legal violations stemmed largely from Amazon’s alleged failure to prevent the offering of counterfeit goods on its sweeping marketplace site.

Yet, while brands and trade groups, alike, seem willing to rally around the assertion that Amazon’s sites are rife with counterfeit or otherwise infringing products, there may be more to the oft-chilly dynamic between the $1 trillion e-commerce empire and third-party brands than that. That is what Amazon’s Vice President of Public Policy Brian Huseman asserted in the 4-page letter he wrote to Acting Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Innovation and Intellectual Property Daniel Lee in response to the American Apparel and Footwear Association’s quest to get Amazon on the government’s “Notorious Markets” list.

5. LVMH’s Failed Stake Building Effort Resurfaces in Enduring Hermès Family Investigation

Ten years ago, on an otherwise ordinary day in October 2010, news broke that LVMH chairman Bernard Arnault had built up a sizable stake in Hermès. The Paris-based luxury goods conglomerate revealed in a statement, as required by French finance law, that it had acquired a 14.2 percent stake in the then-173-year old Hermès, in which the Puech, Dumas and Guerrands families controlled a 73.4 percent stake. What would come to be revealed in due time was that LVMH’s revelation that day was only the first of several that could be expected, and despite the agreement among “the majority of the Hermès families that Arnault was an unwanted interloper” with no place at their ownership table, LVMH’s notoriously ruthless leader was undeterred.

The deals that enabled Arnault to quietly build up a stake in Hermès would come under the microscope in rival lawsuits that Hermès and LVMH would file against one another in 2012. But after executives for LVMH and Hermès ultimately made peace in court in September 2014, trouble was brewing behind the scenes for the Hermès families, and on the heels of LVMH distributing its Hermès stake in late 2014, Hermès – “sparked by tension in the family after LVMH’s 2010 surprise stake building,” filed a criminal complaint against Nicolas Puech, asserting that the great-great-grandson of Hermès founder Thierry Hermès, and cousin to former Hermès chairman Jean-Louis Dumas, had falsely disclosed that he still owned nearly 6 percent of the company’s stock.

6. Remember “Blanding”? Well, Websites Are All Starting to Look the Same Now, Too

Websites are all starting to look alike. Across all three metrics – color, layout and AI-generated attributes – the average differences between websites peaked between 2008 and 2010, and then decreased between 2010 and 2016. Layout differences decreased the most – declining over 30 percent – in that latter time frame. These findings confirm the aforementioned suspicions that websites are becoming more similar. As for what can be made of this creeping conformity, on one hand, adhering to trends is totally normal in other realms of design, like fashion or architecture. And if designs are becoming more similar because they are using the same libraries, that means they are likely becoming more accessible to the visually impaired, since popular libraries are generally better at conforming to accessibility standards than individual developers. They are also more user-friendly, since new visitors will not have to spend as much time learning how to navigate the site’s pages. These are good things.

On the other hand, the internet is a shared cultural artifact, and its distributed, decentralized nature is what makes it unique. As home pages and fully customizable platforms like NeoPets and MySpace fade into memory, web design may lose much of its power as a form of creative expression. The Mozilla Foundation has argued that consolidation is bad for the “health” of the internet, and the aesthetics of the web could be seen as one element of its well-being.

7. How “Progressive,” Millennial-Focused Workplaces Have Tried to Keep Employees’ Discrimination Claims Quiet

In light of a larger dialogue about racial justice, social media and traditional media outlets, alike, have been flooded with stories of employees alleging harassment and discrimination, and sharing other stories of microaggressions that resulted in hostile workplaces. This groundswell of allegations is reminiscent of the #MeToo movement that swept the globe in 2017, which saw many women come forward about workplace sexism, harassment, and sometimes, even allegations of assault. This time, however, some things will be different. After the rise of #MeToo, legislatures around the country adopted new statutes aiming to protect against this kind of behavior, and the contractual obligations that had successfully silenced it.

The evolving treatment of non-disclosure agreements – or NDAs – has been particularly striking in the wake of #MeToo. While these common contractual agreements (or confidentiality terms reminiscent of an NDA), continue to find their way into an ever-increasing number of situations – from employment agreements and severance packages to visitor logs at co-working spaces and pre-job interview paperwork, they are not always as sweeping or iron-clad as they may seem. In fact, NDAs and confidentiality terms are frequently limited by law in terms of the subject matter for which they can obligate silence.

8. How Pandemics Past and Present, Fuel the Fall of Small Businesses and the Rise of Mega-Corporations

One of less-often discussed consequences of the Black Death is an important one: the rise of wealthy entrepreneurs and their ventures. Although the Black Death caused short-term losses for Europe’s largest companies, in the long term, these businesses concentrated their assets and gained a greater share of the market, as well as increased influence with governments. This has strong parallels with our current COVID-19 reality. While small companies are being forced to rely upon government support to prevent collapse, others, such as giants like Amazon, are profiting handsomely due to the new trading conditions.

The mid-14th century economy is too removed from the size, speed, and interconnectedness of the modern market to give exact comparisons, but we can certainly see some parallels with the way that the Black Death accelerated the domination of key markets by a handful of mega-corporations, which is likely to ensue in the wake of the COVID-pandemic.

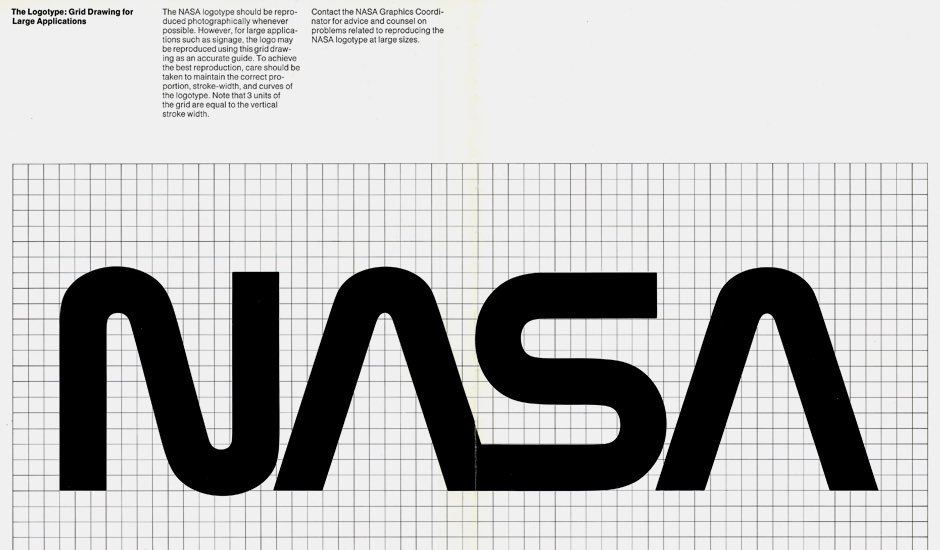

9. As NASA Reintroduces its “Worm” Logo, a Look at the Branding & Re-Branding of the Federal Space Agency

In the late 1950s, a Cleveland Institute of Art graduate named James Modarelli was in the midst of his tenure at the laboratory that would become the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (“NASA”) Glenn Research Center just outside of Cleveland, Ohio. At the time, the then-43 year old National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics was being spun into a new agency, the one that we now know as NASA, and the restructuring called for a change in name and branding. So, the powers that be called on the space agency’s employees to submit designs for a new logo, and that is precisely what Modarelli did.

Inspired by a 1958 visit to the Ames Unitary Plan Wind Tunnel in Mountain View, California, where he was particularly impressed by a model of a radical supersonic airplane, the design of the plane, namely its “cambered, twisted arrow wing,” served as the inspiration behind the design of the official NASA seal and a similar, but less formal, symbol that Modarelli submitted a year later.

10. Four Lawsuits, Corporate “Bullying,” and an Alleged Pattern of Rampant Copying: The History of Nike v. Skechers

In the $62.5 billion-plus global sneaker market, the competition is fierce, the costs associated with the intensive research and development that goes into designing and manufacturing footwear are high, and the revenues that can be generated from single styles collections can race past the $1 billion mark for standouts like Nike’s Flyknits or adidas’ Stan Smith and the Superstar models. This means that the stakes are high amongst the market’s key players, and the chance that litigation will come into play among them is even higher.

Nike and adidas have long made headlines in connection with their history of legal battles, centering on their respective knitted technologies, for instance, which spawned an international battle beginning at the very same time as he London Olympics in 2012, and while there is likely no end in sight to the fights they wage against one another in their quest to outfit consumers across the globe, another rivalry has been spilling over into the courts: Nike versus Skechers.

11. In Order to Operate (More) Sustainably, Brands Need to Do More than Simply Skip Fashion Week

Saint Laurent made headlines in April when it announced that it will not present its collections “in any of the pre-set schedules of 2020.” In other words, it is opting out of the main fashion calendar, the one that dictates that brands present their seasonal collections in the respective fashion capitals each February/March and September/October for womenswear, and January and June for menswear. In furtherance of this rather-noteworthy change, the Paris-based brand says that it will “take ownership of its calendar and launch its collections following a plan conceived with an up-to-date perspective, driven by creativity” as part of a larger effort “to take control of its pace and reshape its schedule.”

With such an announcement in mind, Saint Laurent is rightfully being praised for being the first big brand to more or less break the traditional cycle in favor of a presumably more measured – and more sustainable – approach. After all, in recent years, sustainability has come to dominate much of the conversation in the industry, as nearly-countless articles have detailed just how unsustainable the bi-annual or quarterly show model – or realistically, even more frequent than that if you count the oft over-the-top pre-season and couture presentations by brands – currently is.

12. From Intangible Assets to Price-Setting Power: What Makes a Brand a Brand?

What makes a brand a brand? That is the interesting – albeit complicated – question that Bernstein’s Bruno Monteyne and Luca Solca set out to answer in a recent client note. In doing so, the analysts consider a handful of other questions, namely, “What differentiates brands from commodities? Why do [brands] make so much money, and what determines how much money they can make?,” and come up with the following assertion: “a brand is a license to tax our emotions and dreams.”

Delving into the definition of a “brand” in a more concrete manner, Monteyne and Solca point to the “big gap between a marketer’s definition of what a brand is and what a brand, instead, appears to be in the … minds of consumers.” On one hand, they say that “marketers have a more factual assessment of brands: specific products and formulations, advertising campaigns over the years, design and logo choices and evolution, ‘story-telling,’ testimonials and representatives, and so on.”

13. Can Bottega Veneta’s Daniel Lee Go Beyond the “It” Bag? Or Better Yet … Does He Need to?

Blockbuster sales, industry awards, and a recent New York Times profile have put Bottega Veneta creative director Daniel Lee in the spotlight. Those same elements paired with his new-found high fashion fame have led some to question – explicitly or otherwise – whether Bottega’s 34-year old wunderkind can go beyond the “it” bag, which is precisely the thing has brought about so much of the sales and praise being attributed to this relative new-comer to the big leagues of the fashion industry.

It is a valid question. After all, branching out beyond bags is largely what François-Henri Pinault, the Chairman and CEO of Bottega Veneta’s parent company Kering, and Bottega’s former chief executive officer Claus-Dietrich Lahrs (who has since been succeeded by Bartolomeo Rongone) aimed to achieve when they hired Lee a year and a half ago. As the New York Times’ Vanessa Friedman wrote in February, “In 2018, Mr. Pinault and [Mr.] Lahrs had decided that if the brand were ever to move to the next level, Bottega had to become known not just for leather goods … but also for its ready-to-wear.”

14. World-Famous Trademarks and Millions of Dollars of Counterfeits: A Look at Nike’s Escalating Fight Against Fakes

With the rise of large-scale counterfeiting operations and the ability of counterfeiters to hide behind fake identities facilitated by e-commerce, brands have evolved their strategies, and over the past 10 years, Nike’s enforcement efforts have come to include an number of interesting – and inventive – elements that go beyond the traditional cat-and-mouse game that sees trademark holders uniformly chasing counterfeit sellers, such as those that populate online e-commerce marketplaces and counterfeit havens, such as New York’s Canal Street.

One new tactic fashioned by the sportswear giant, in particular, started to emerge in 2010, when “Nike [began] approaching licensed U.S. customs brokers and requesting the broker’s assistance to provide it with information regarding a specific (or multiple) shipments,” Deanna Clark-Esposito, an international trade attorney, reported at the time. “In an effort to assist Nike, brokers (naively) handed over information, only to be later ‘thanked’ by Nike in the form of a lawsuit with allegations ‘supported’ by the very papers the broker provided it with.”

15. “Homogenous,” Instagram Apologies Raise Questions About Modern Brands and their “Mission-Centric” Branding

2020 saw no shortage of markedly similar apologies from some of the market’s buzziest brands, making it almost impossible not to wonder whether these utterly-Instagrammable apologies are merely the latest efforts by brands to not only save face (and save their bottom-lines during an already-difficult time) but also to attempt to bolster the often-explicitly “mission” oriented nature of their operations. After all, aside from disrupting the traditional retail model by cutting out the middleman and going all-in on social media content-as-advertising, this morals or ethics-driven approach is a large part of what initially helped to set these companies apart from other, more established market entities.

At the same time, broader expectations about how these companies conduct themselves have also entered into the mix given that they are marketing – and to some extent, profiting from – a larger message of morals, making allegations of racial discrimination and reported attempts to stand in the way of unionization efforts, for example, even more problematic.