image: Rouge Fashion Book

In September 2005, China got its first-ever native issue of Vogue magazine. The sixteenth international edition of the esteemed fashion bible, Vogue China’s debut issue, under the watch of editor-in-chief Angelica Cheung, had been more than two years in the making. Now, almost 13 years later, Beijing-based Vogue China releases 16 issues per year and boasts a circulation of roughly 1.5 million copies. Its monthly page views, according to Condè Nast International, exceed 371 million. For some perspective, American Vogue’s digital footprint is about 67.2 million page views per month.

Meanwhile, outside of the circle of big media giants, such as Condé Nast, which owns titles ranging from Vogue, Vanity Fair, and W magazines to Brides, Bon Appétit, GQ, and Wired, a world of unconventional perspectives is emerging in print. This is, in large part, the result of editors and other creatives aiming to exercise greater creative freedom and to challenge mainstream media narratives, which are oftentimes significantly impacted – or more realistically, dictated – by the agendas of big-name advertisers.

Valerie Wickes, the co-founder of Beauty Papers, told the FT last fall that while running her advertising and brand consultancy firm, she had grown increasingly frustrated with conventional fashion publications. “I was aware of a narrowing in perception of how women and men should look and behave. At the same time, magazines were increasingly controlling editorial to order, so creativity and artistry was being strangled and any authority was disappearing.”

Her Beauty Papers’ co-founder, make-up artist Maxine Leonard, had some of the same frustrations; she was longing to see more diverse, creative and honest coverage in terms of beauty content. So, the two women, in conversation while on a train together from Paris to London, decided to start their own publication, and they are not alone.

In addition to a growing breed of indie fashion, beauty, and cultural content in the West, independent fashion magazines are on the rise in China, as well, as editors are opting to highlight perspectives that are not always included on the pages of the 13-year old Vogue China.

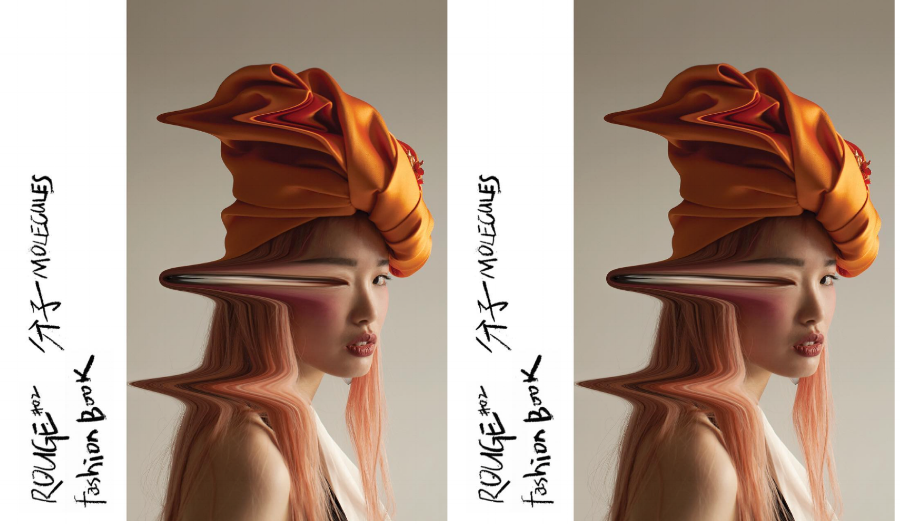

Shanghai-based Lily Chou, a 22-year-old with a master’s degree in fashion history from Parsons, told SCMP that she decided to launch Rouge Fashion Book, a bi-annual publication because she had “passed the phase where Vogue is everything I need.” She and Rouge Fashion Book’s other co-founder Calvin Luo, an independent fashion designer, wanted to “create something edgy, arty and fashion forward-thinking for the Chinese market,” she says.

The demand for alternate takes on fashion and beauty is part of a growing sentiment in the Far East, says Leaf Greener, a former fashion editor at Elle China and now the publisher of Leaf, a niche WeChat-based magazine. “It’s the same as the consumer evolution. They start with big labels and then they get to know themselves and they try new brands, maybe some independent designers, it’s the same thing as the fashion media,” she says.

Despite such budding interest in alternative media outlets, setting up shop by way of an indie title is not as easy in China as it is in France or U.S., for instance. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, “The Chinese government has long kept tight reins on both traditional and new media to avoid potential subversion of its authority. Its tactics often entail strict media controls using monitoring systems and firewalls, shuttering publications or websites, and jailing dissident journalists, bloggers, and activists.”

Such regulation has been increased further now that Chinese internet companies are required to sign the “Public Pledge on Self-Regulation and Professional Ethics for China Internet Industry,” and in light of the passage of China’s Online Publishing Service Administrative Rules, which were enacted in March 2016. The Online Publishing Rules entail a lengthy application process for an entity to become lawfully able to provide internet publishing services. Such provisions require publishers to obtain a Publishing Service License before engaging in internet publishing services and to obtain a separate license to distribute media outside of China’s borders.

The mainland’s strict media regulations focus most significantly on big-name titles, they not lost on independent magazines, which face something of an uphill battle as a result. Samantha Culp – a writer, strategist, and creative producer, who splits time between Los Angeles and Shanghai – told SCMP that indie magazines, particularly ones that exist only in print, have a bit more freedom due to the small-scale nature of their operations, due to the chance that the Chinese government may never encounter the magazine. It is, however, “a gamble,” she says.

As for Rouge Fashion Book, the magazine’s circulation of roughly 1,000 issues is stocked by sellers in both in China and internationally, including on the Tate Modern’s website, thanks to the editors’ decision to publish two versions of each edition, “one with a Chinese international standard book number [ISBN], which conforms to local laws and another with an American ISBN that is sold overseas with a special licence to distribute foreign media.”

Ms. Chou says that while she is, in fact, “afraid of censorship in China,” she has carried on publishing her buzzy publication, nonetheless.