image: adidas

“Bully.” That is the word that Forever 21 used to describe adidas in the lawsuit it filed in March 2017. The Los Angeles-based fashion chain, which brings in more than $4 billion in revenue per year selling runway copycats to young adults for cheap, alleged that the German sportswear giant has been engaged in a scheme to “secure federal trademark registrations for use of three, parallel stripes placed in specific locations on certain shoes and clothing.”

In the process, Forever 21 says adidas has become “well known for aggressively enforcing” those “perceived rights against others,” thereby creating a “monopoly” on a routine design staple with “no defined boundaries.”

“Tired of operating with a cloud over its head with regard to its right to design and sell clothing items bearing ornamental/decorative stripes,” Forever 21 filed suit, telling a federal court in California that “adidas should not be allowed to claim that [it], alone, has a monopoly on all striped clothing.” Forever 21 also stated that it is “unwilling to stop doing something” – using stripes on its garments and accessories – that “it has every right to do.”

Forever 21 alleges that unlike adidas, which uses the 3 stripes as an indicator of its brand, its use of stripes is merely ornamental and does not serve a source-identifying function (i.e., the stripes are simply being used as stripes and not being used as a trademark).

The fashion retailer’s lawsuit, which is still underway, is more than a run-of-the-mill trademark infringement matter. Instead, it speaks to – or maybe more accurately, questions – the allowable expansiveness of the rights afforded by trademark law, which generally grants individuals or companies the exclusive right to use a trademark – be it a name, logo, specific element of packaging, etc. – on specific categories of goods in order to distinguish their products from the products of their competitors.

In furtherance of its goal of aiding consumers in easily distinguishing between products and making purchasing decisions, trademark law also aims to prevent confusion amongst consumers as to the source of a product, thereby giving rise to trademark infringement claims.

According to Forever 21, adidas is (and has been for some time been) taking “its claims too far, essentially asserting that no item of clothing can have any number of stripes in any location without infringing [its] trademarks.”

Seemingly unscathed by the criticism, a representative for adidas told TFL after being hit with the Forever 21 lawsuit that it will “continue to vigorously protect [its] rights and will continue to take action in case of infringements.” It will also, as indicated by a recently-filed trademark application, continue to work to amass registrations for those trademark rights.

In a move to add yet another federal registration to its beefy arsenal, adidas filed an application with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office last month for a mark that “consists of a classic tennis-shoe profile with three rows of perforations positioned in the area between the laces and the sole, stitching across the sides of each shoe enclosing the perforations, a mustache-shaped heel patch, and a flat outsole.” If that description sounds familiar, that is because it is the design of the brand’s famous Stan Smith sneaker.

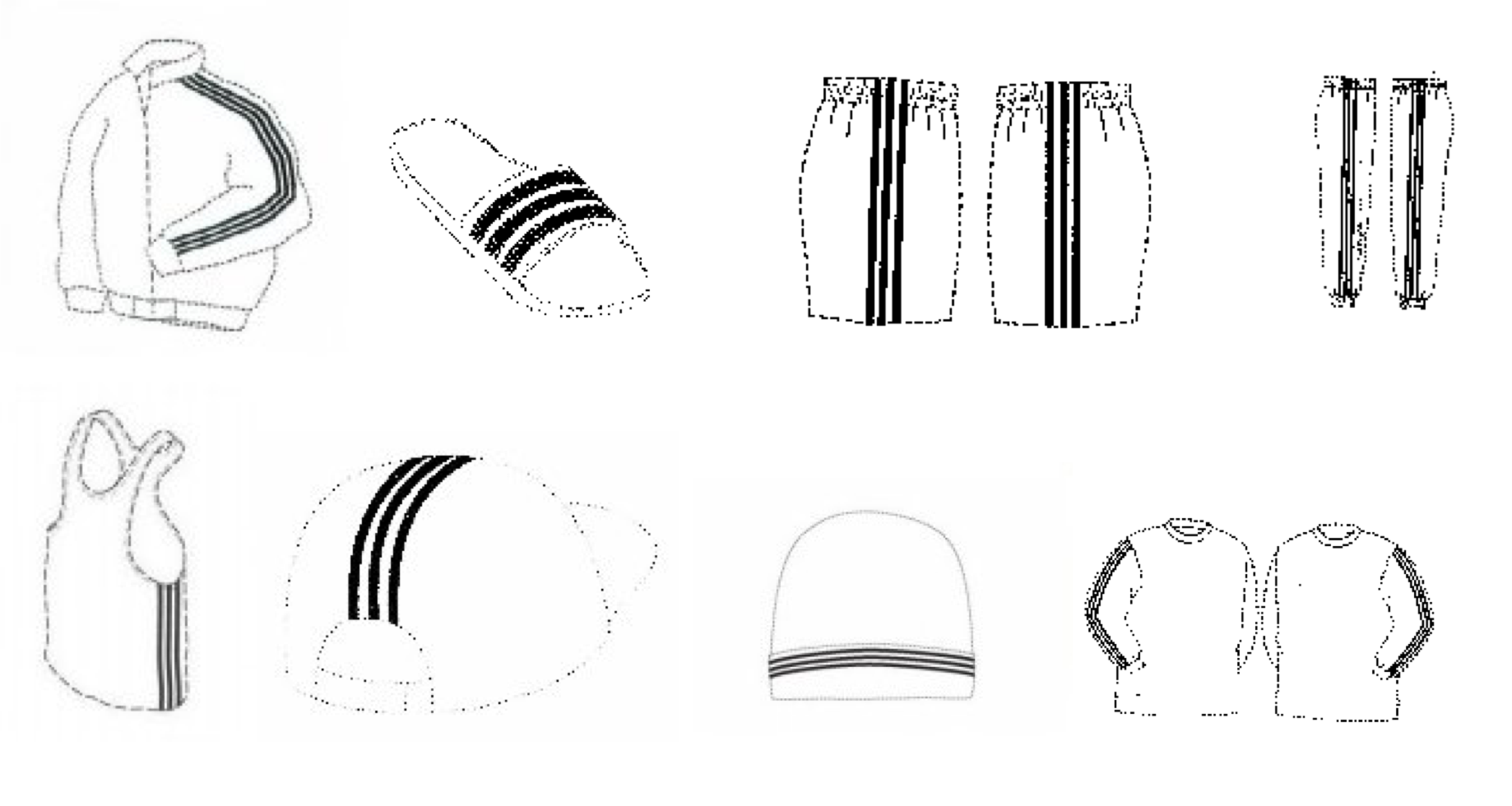

The application joins a long list of already-issued registrations for three parallel stripes running along the sleeve of a shirt, jacket, and on the length of each leg of the pants or shorts.

Beyond Forever 21, the German sportswear giant has not found favor among many for its aggressive approach to what at least some experts are categorizing as an attempt to claim ownership of stripes more broadly. As Mike Masnick, the founder of TechDirt, wrote back in 2008, on the heels of adidas winning a $305 million ruling against Payless Shoes’ parent company, Collective Brands, “We’ve discussed over and over again how companies misuse trademark law, believing that it gives them total ownership over the mark, rather than the fact that it’s really designed to prevent consumer confusion.”

“This is what happens when people talk about trademark as being ‘intellectual property,’” Masnick continued. “It gets them thinking that it creates total ownership over something as basic as stripes.”

Masnick is not the only one to have made this argument. Right around the same time, Joe Mullin took on the merits of adidas’ “‘we-own-stripes’ litigation campaign on his site, Prior Art, writing, “Unless shoes actually have fake ‘adidas’ tags, it’s hard for me to believe anyone was confused about the source of the product [even if they make use of stripes].”

A number of adidas’ trademark drawings

Yet, despite what many experts have conjunctively deemed to be an aggressive and improper reliance on trademark law to protect uses that almost certainly are not confusing, no shortage of courts and intellectual property bodies have sided with adidas – save for, say, the European Union Intellectual Property Office’s Second Board of Appeal, which held last year that one of adidas’ 3-stripe trademark registrations is, in fact, invalid, as it amounts to mere decoration and lacks “acquired distinctiveness” (i.e., the public has not come to associate the mark on its own with adidas).

Yes, years after its Payless victory, adidas is still winning. As recently as this May, for instance, it was handed a preliminary victory in the case it filed against Skechers in September 2015. In a 43-page opinion, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the sportswear giant in its effort to prevent rival Skechers from selling sneakers that adidas alleged were “confusingly” similar to its classic Stan Smith.

Foley Hoag’s Natasha Reed noted the general strength of adidas’ marks in an article in 2016, writing, “While stripes and other shapes may seem commonplace for fashion products, the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon has held multiple times that adidas’ 3-stripe design is a famous trademark.” As a result, “adidas likely enjoys a wider range of legal protection, particularly against sneaker designs bearing parallel stripes on the side of the product.”

With this in mind, any “small differences between the number of stripes, whether it be 2 stripes, or even 4 stripes, may have little bearing on the infringement analysis, especially if the overall sneaker design looks similar to an adidas product.”

And that likely does not bode well for … well, …. anyone.